In Part One: Collecting, Compiling & the Construction of Cultural Histories, it was noted that artists often find it difficult to retain and manage accumulated items in their care. Questions regarding the disposition of materials are particularly challenging for the artist engaged in non-traditional practices. During the discussion in Part Two: The Disposition of Decades-Old Correspondence, our focus was directed to practitioners of mail art and their apprehension of what to do with decades of correspondence and collateral items in the face of institutional disregard. Part Three: An Immediately Quaint Form that Excused Itself from History examined the slow march of Fluxus toward institutional acceptance, and the similar struggle mail art is currently undergoing in attracting scholarly validity. The present text describes steps being made to rectify the situation.

Part Four: Cataloging Community

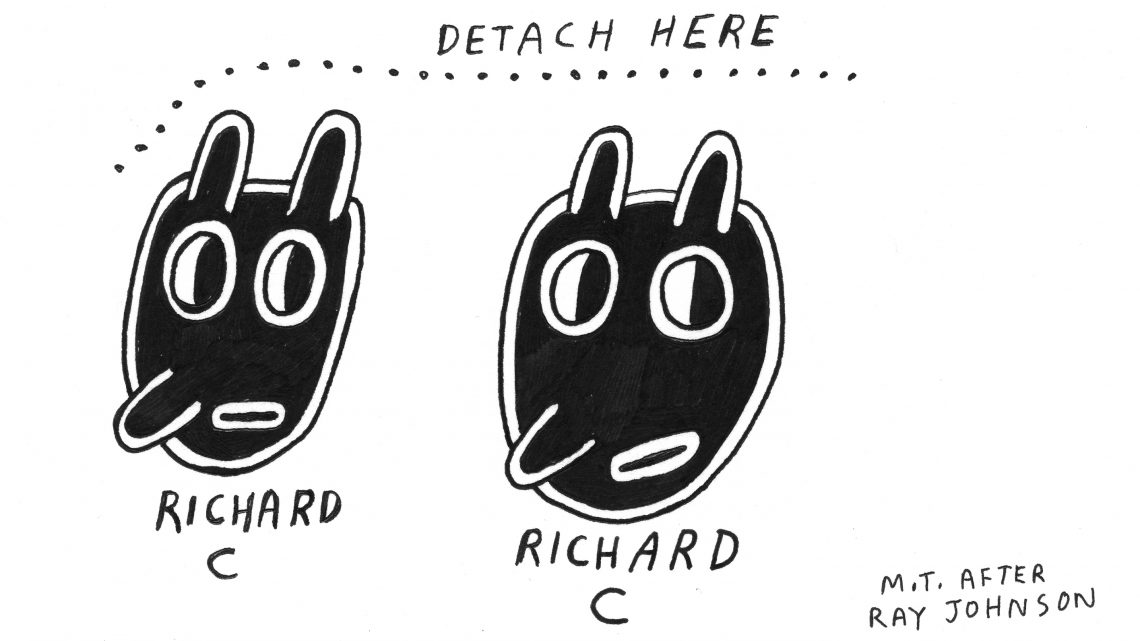

Ray Johnson envisioned his postal activities as a communal activity from the start. Schooled at Black Mountain College in the late 1940s, he kept up with his classmates and instructors through the post, as well as personal contacts, forming lifelong relationships with many of them. Endeavoring to start a design business after graduation, he began distributing information and graphic examples through the mail. Circumventing the gallery system, he also began mailing moticos—shaped cardboard with minimal ink additions, exhibited in the streets, as well as through the post—which would become the linchpin in Johnson’s linking of like-minded individuals. This alternative to standard artistic distribution channels distanced from the gallery/museum system appealed to fellow artists, including those associated with Fluxus and Japanese Gutai, who were searching for new ways of resuscitating art by integrating it with everyday activities.

One of Johnson’s main strategies in maintaining and stimulating community, was his decree to “add and pass” enclosed postal works to an either known or unknown third party. By 1962, Johnson’s mailings attained widespread underground attention (he was commonly known as “the most famous unknown artist in New York”) and were named when correspondent E. M. Plunkett applied the term New York Correspondence School to Johnson’s heretofore unspecified activity.1

As his circle of correspondents rippled outward, Johnson began testing the strength of the network he was weaving, inviting various correspondents to thematic meetings and gauging their responses. Another example of Johnson’s commitment to community was his selection of personalities for an ongoing series of silhouette drawings, conducted under rigorous guidelines. Through this selection of sitters, Johnson was able to visually articulate a community of contemporaries, whom he believed were setting the cultural agenda of his time.

Replicating the sense of community he experienced at Black Mountain, Johnson instituted new artistic practices that were to have global cultural implications. Today, social practice is a commonly accepted means of extending the creative act into the everyday. Postal exchange among artists provoking human interaction portended this development some 50 years ago. Mail art anticipated the rise of multiculturalism, democratized cultural exchange, and allowed for engagement from participants outside of a cultural center Mail art went viral globally well before the Internet, anticipating the rise of multiculturalism, democratized cultural exchange and the displacement of a cultural center. As early as 1969, Michael Morris and Vincent Trasov had established an “Image Bank Correspondence Exchange,” which listed subjects of correspondent’s interest to connect the participants in the emerging Eternal Network.2

Communication, distribution, and networking became integral concerns of the contemporary artist, anticipating the growing self-sufficiency of the individual in the dissolution of institutional structures and the rise of disruptive enterprises. By immersing themselves in these practices, mail artists anticipated the changing course of a new millennial consciousness. Our widespread dependence on the Internet for timely long distance communication and creative exchange is eerily similar to previous reliance on the postal system’s analog reach across geographical and cultural barriers in the deliverance of art and information.

In 1971, I obtained a degree in Information Studies at Syracuse University and began working in public libraries. This provided me with a secure foundation from which to engage in mail art, having access to both photocopy and mailing privileges (which I admittedly abused). Simultaneously, I began working part-time as an archivist for the Oneida Community Historical Society, composed of descendants of the Upstate New York utopian community, that existed from 1848-1881. The Oneida Community grew in a manner similar to that of mail art, through postal communication among the membership with those seeking admission. This contemporary communal endeavor is what initially drew me to mail art.

I relocated from upstate New York to Dallas, Texas in 1981, and continued with both librarianship and mail art. I opened a gallery that featured artists I was corresponding with (Ray Johnson, Anna Banana, Monty Cantsin, et al.) and began extensive travels to visit mail artists in Europe, Latin America, the Soviet Union, and Japan. These gallery shows and personal encounters added to my growing collection of mail art.

Professionally, I began writing and attending panel discussions on artist’s archives, most notably at conferences sponsored by the Art Libraries Society of North America founded by Judith Hoffberg, herself an active mail artist.

The contacts made in ARLIS later proved invaluable. After working at the Dallas Public Library for 15 years, I relocated to San Francisco in 1995 to work with Bill Gaglione at the Stamp Art Gallery. After three years mounting some 50 shows with attendant catalogs and rubber stamp box sets, the gallery closed. I decided to put together collections of mail art to see if I could place them institutionally. I never gave a second thought to approaching museum curators about this. Just as Maciunas had achieved success in placing Fluxus in libraries, well before museums were versed in his accomplishments, I knew that curators had no interest in the material, but librarians, I believed, would be drawn to documents of mail art. It was the librarians that collected exhibition catalogs, artists’ books and periodicals, and I directed my attention towards them.

You can’t approach a potential recipient with the line, “I have a lot of material that I think you may be interested in.” They want to know exactly what you have, especially fastidious librarians. At the turn of the millennium, I began to sort my collection of exhibition documentation from the general collection. After the initial sort, I categorized the invitations, catalogs, and posters by year, and within that, by country and curator. Each exhibition catalog (poster or postcard) was placed in a separate folder. That was the easy part. The time consuming portion commenced when this material needed to be enumerated.

Folder by folder, I described what was contained within. The inventory delineated the curator, title, physical location, dates of exhibition and the resultant documentation. Catalogs were described as to the number of pages, printing medium, physical size, and content. Unnumbered pages were indicated by parenthesis. Introductions, essays, and reproductions were noted. Annotations were added to highlight the significance of a specific show.

The results took the following form:

1970

United States of America

Johnson, Ray and Tucker, Marcia. New York Correspondence School Exhibition. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, New York. September 2-October 6, 1970. 4 pages. Offset. 7 x 7 inches. Essay by William S. Wilson, “Drop a Line.” Participant list. A very early mail art show (Johnson collaborated with Joseph Raphael the previous year on a similar exhibition at Sacramento State College) that set the tone for the explosion of exhibitions that followed in the next two decades. Organized by Ray Johnson and Whitney curator Marcia Tucker, the show contained the work of the 106 participants listed on the last page of this brief brochure. Includes the essay, “Drop a Line,” by noted Johnsonian scholar William S. Wilson.

McShine, Kynaston L. Information. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, New York. July 2-September 20, 1970. 207 pages. Offset. 11 x 8 ½ inches. Introduction by the curator. Reproductions. Bibliography. (In organizing an international activity report of non-traditional artists, the Museum of Modern Art assembled a show in the manner of a mail art exhibition—printing, rather than exhibiting, anything that was submitted. This occurred just a month before the New York Correspondence School exhibition at the Whitney [see entry under Ray Johnson]. Something was definitely in the air at the start of the decade.

1972

England

Mayor, David. Fluxshoe. Exeter, England. November 13-December 2, 1972. Falmouth, England. October 23-31, 1972. 144 pages. Offset. 11 ¾ x 8 ½ inches. Traveling exhibition. Includes bibliography. Reproductions. A Beau Geste Press publication. An important early mail art show that brought together the Fluxus generation with the emerging Eternal Network of Mail Artists. Contains excellent biographical material about the artists at the end of the work, accompanied by a bibliography of relevant books and periodicals.

Crozier, Robin. Robin Crozier Retrospective 1936-1972. Bede Gallery, Jarrow, England. April 29-May 28, (1972). Poster. Offset (2 color). 25 ¾ x 17 ½ inches. Exhibition by the Dean of English Mail Art.

Uruguay

Padin, Clemente. Exposion Exhaustiva de la Nueve Poesia. Galeria U, Montevideo, Uruguay. February 7-April 5, 1972. 19 pages. 8 ½ x 6 ¾ inches. 350 artists from 30 countries.

1973

England

Ehrenberg, Felipe; Mayor, David; and Wright, Terry. Fluxshoe: Add End A: 72-73. Croydon, England. January 15-26, 1973. Oxford, England. February 10-25, 1973. Cardiff, England. June 14, 1973. Nottingham, England. June 6-19, 1973. Backburn, England. July 6-21, 1973. Hastings, England. August 17-24, 1973. Falmouth, England. October 23-31, 1973. Beau Geste Press, Cullompton, England. Unpaged portfolio, including poster, postcard, and original artworks by Robin Crozier, Entre Tot, et al. Mixed media. Folder, 9 x 14 inches. Introduction. Includes an essay by George Brecht, “Something About Fluxus.” Newspaper reviews. (*As the Fluxshoe exhibition traveled, and performances were conducted at the various stops, documentation accumulated, newspaper reviews were compiled, late arrivals added [including a sheet of Robert Watts, Fluxpost/17-17, postage stamps], all of which were assembled in a folder, and issued as an addenda to the previous publication.)

New Zealand

Reid, Terry. Inch Show. Auckland University, Auckland, New Zealand. 1973. 16 pages. Newspaper format. 22 ½ x17 inches. Essays by Ken Friedman and George Brecht. Illustrated.

United States of America

Davi Det Hompson. An International Cyclopedia of Plans and Occurrences. Anderson Gallery, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia. March 15-April 10, 1973. Poster. Offset. (9 ½ x 6 inches folded, 37 x 23 ½ inches unfolded). Participant list. Important early show, bringing together diverse factions of an emerging network. *This one has good karma written all over it. Hompson was a sometimes Fluxist and early mail artist, who attracted many early networkers (Clemente Padin, Jiri Valoch, Edgardo-Antonio Vigo, Wolf Vostell, William Wilson). He writes an introduction acknowledging the assistance of Fluxus West, the NYCS and Image Bank. One of the first instances of a self-conscious network recognizing and celebrating itself.

Friedman, Ken. Omaha Flow Systems. Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska. April 1-24, 1973. Magazine Reprint. Essay by Friedman, “Flowing in Omaha,” reprinted courtesy of Art & Artists, August 1973, London. 4 pages. 11 x 8 ½ inches.

Uruguay

Padin, Clemente. Theme and Variations. Gallery U, Montevideo, Uruguay. September 1973. Unpaged. 8 ½ x 6 ¾ inches. Offset. 30 participants (Robert Filliou, George Brecht, Bern Porter, Guillermo Deisler, Lowell Darling, et al). Reproductions. Printed in October 1986 in 100 copies.

At the conclusion of the project, some 1,600 mail art exhibition documents from 54 countries were inventoried. While the majority of the items were acquired as a result of active participation in the exhibition process, others were donated for research purposes in the compilation of my International Artist Cooperation: Mail Art Shows, 1970-1985, (Dallas Public Library, 1986) and the book, Mail Art: An Annotated Bibliography (Scarecrow Press, 1991). Other items were acquired through purchase and trade with many of the leading practitioners of the medium, often during personal visits.

Through contacts made in ARLIS, I approached the Getty Research Institute to see if they were interested in acquiring the 1,600 item collection. The Getty had previously purchased the Jean Brown Archive, containing Fluxus and Mail Art, and I saw this as a compliment to her collection. Once the decision was made by the Getty to accept the material, I donated the label copy of the 1986 Dallas Public Library exhibition, Mail Art Shows, 1970-1985, the notes from the periodical section of the mail art bibliography, and 1,500 exhibition invitations to broaden the research potential for future scholars of the field.

At the end of Part Three of this series, I promised explication of the placement of Latin American and Eastern European periodicals in the Museum of Modern Art, New York, exhibition Transmissions: Art in Eastern Europe and Latin America, 1960-1980, containing mail art related works by Paulo Bruscky, Ulises Carrión, Clemente Padín, Pawel Petasz, and Edgardo Antonio Vigo, among others. The museum had previously displayed mail art in an exhibition space reserved for the library, but to my knowledge, before this exhibition, never in the museum proper.

In November 2001, I began pulling all the mail art publications and zines from my archive, which were stored in some 250 storage boxes. At the end of this initial sort, some 70 boxes were identified as publications. These included mail art periodicals, zines, archival material from Friedman’s Factsheet 5 and Ashley Parker Owen’s Global Mail, as well as the periodical research notes I had used during the development of my 1991 book, Mail Art: An Annotated Bibliography. After this initial sort, mail art periodicals were isolated for cataloging and annotating. This process lasted two months.

Specific titles were designated as “mail art periodicals” because of their usefulness in researching mail art as a specific area of the late 20th century cultural avant-garde. The vast majority of the periodicals were generated by those involved in the genre, usually in editions no larger than a few hundred. Other periodic publications with a wider focus were included because of their persistent attention to mail art, or had specific numbers devoted to the genre.

The term “periodical” seemed preferable to “magazine,” which implied a publication with various sections, including letters to the editor, articles, announcements, reviews, etc. Periodicals, on the other hand, could be defined more broadly; a publication issued serially, less confined by traditional magazine formats.

At the start of 2002, I sorted the mail art periodicals by title, creating files (manila folders) in standard storage boxes. By the end of January, the sort was completed, and I began work on an annotated inventory” of the mail art periodicals in the collection. All items were cataloged (title, editor, publisher, location, volume, number, date, medium, size, pages), and annotated to describe both the character and content of the item under examination. Editors’ motivations for publishing were cited, authors and graphic contributors noted, and indication given on the inclusion of reviews, and mail art exhibition, project, and publication opportunities. Quotes were chosen for their value in illuminating a facet of the field.

The final inventory of the collection, completed by the end of March 2002, totaled 610 pages. The final inventory enumerated 3,711 items, consisting of 655 titles published in 34 countries, and housed in 39 storage boxes, containing significant runs of influential mail art publications from 1972-2001. Notebooks were created to present the inventory, illustrated by some 200 cover and interior pages of the periodicals in the collection.

I had sensed MoMA’s interest in the material, and proposed their acquisition of the material to the Chief Librarian. In an ironic twist, library trustee Jon Hendricks was asked to consult on the material’s relevance. Hendricks, a Fluxus archivist, had been in a similar position decades earlier trying to institutionalize Fluxus.

The inability of traditional research institutions to acquire challenging materials at the time of their issue, forces individuals associated with marginal cultures to nurture primary source materials prior to their mainstream acceptance enabling future scholarly study. This “care and feeding” of cultural alternatives at the infancy of their acceptance, is both blessing and curse, rife with discouragement and disappointment, ultimately satisfying through perseverance and strength of purpose.