False Narratives

Pierogi Gallery

155 Suffolk Street New York NY

June 25th – July 31st

Ironically, it is the woman blinded by a facemask who catches my eye. Nadja Bournonville’s portrait sitter for her 2012 C-print, A Collection of Small Grey Stones, wears a navy blue dress and is elegantly posed with hands in her lap, in front of an aged off-white and pink wall. Her portrait is two feet wide by two-and-a-half feet tall from her waist up, a scale that feels close enough to the viewer’s space but also requires close inspection to appreciate the photograph’s tactility: the delicacy of her thin crepe paper mask, the roughness of the chinks in the wall, and the grit of the titular stones she holds in her open palm. The exhibition False Narratives is largely about such second readings and the pleasure of misunderstanding, or the inconsequentiality of accurate versus inaccurate discoveries. My eyes create their own logic while she is blinded, or rather she refuses to answer my hypotheses.

Nadja Bournonville, A Collection of Small Grey Stones, 2012. Analog C-Print, Edition #3/3 + 2 A.P., 29 x 23.25 inches

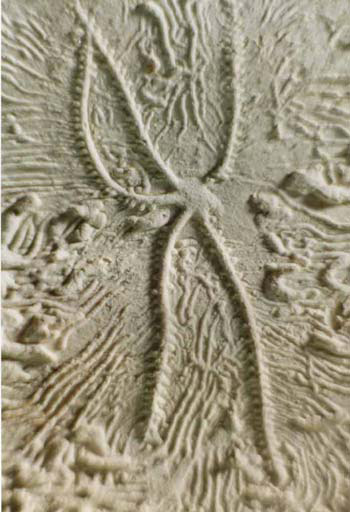

Four prints by Brian Conley from the series Decipherment of Linear X (2004) hang in a grid on the backside of Bournonville’s wall. They appear to represent magnifications of chromosomes or bacteria. Abstract lines and dots squirm and burrow through what I imagine to be the cream and lilac planes of a petri dish. In the corner, also by Conley, tall wooden stakes lean against each other and the wall. Some are painted with the alternating stripes of black and white used to indicate scale in photography. Others are shaped like arrows. The ends of some stakes are streaked with dirt, indexing their removal from the earth. Others are joined with copper pipes.

Brian Conley, Decipherment of Linear X, Installation View at Pierogi

The stakes are in fact Site Markers, more obviously tied to the four prints after close inspection of the photographs, books, and papers laid under glass on a table in the center of the room. Still part of Decipherment of Linear X, the documents reveal extensive research by Conley and fellow scholars into the possible meaning of the marks represented in Conley’s prints. Several of the color photographs on the table depict the aforementioned site markers pointing to objects in the grass off the side of a road. Others depict the large sticks and logs found at those points, each with incisions visually similar to those in Conley’s prints. Now these marks are recognizable as those made by small insects, like the beetles pictured on some pages of nearby texts. After reading the pages open in each book and returning to the prints and photographs, it becomes clear that some texts analyze tablets of an ancient language, Linear B, while others analyze Conley’s sticks as if they were also intentionally rendered text, Linear X. The confusion between “real” and insect-derived mark-making is confused further by the fact that the pages of research on Conley’s logs look aged and are accompanied by black-and-white versions of his photographs. Conley has also made his own tablets from the sticks by rolling them through clay to create ceramic Tablets (2004); numbers 2, 3, 6, and 18 in the series are shown here.

Brian Conley, Decipherment of Linear X (X-Ca-Bc-001), 2004. Archival digital print, Edition 2 of 5, 20 x 13.5 inches

Through the assemblage of media and confusion of temporalities, Conley has simultaneously manufactured a new language, field of research, archive, and set of artifacts while casting doubt upon the accuracy or relevancy of researchers’ earlier deciphering of Linear B, the “real” ancient tablet language.

Though one could draw the parallel of Bournonville’s subject being blinded and Conley’s beetles being unable to communicate, Conley resists reductive conclusions. One of his commissioned researchers has written an article on “Ambrosia beetles and genetic intelligence,” suggesting that there are realms of knowledge beyond human modes of perception. The faux-Rosetta stones then reveal that manufactured truths and histories may be just as plausible and scientifically provocative as supposedly authentic histories (which, of course, are often already more subjective than objective).

Nadja Bournonville, Some Marks, a Square and Figure (triptych), 2012. Analog C-print, Ed. #2/3 + 2 A.P, 29 x 23.25 inches each

With this in mind, it is easier to imagine Nadja Bournonville’s nearby triptych, Some Marks, a Square and Figure (2012), as a narrative illustration. Each C-print depicts a dirt-covered wooden floor ending at a more recently constructed wall. In the image on the left, on the floor, three white boards printed with large black numbers sit on clumsy tripods of wooden sticks; in the middle, a large black board sits behind the number 3; on the right, a barefoot woman replaces the black board. In her black dress, as she pulls both ends of a rope tighter around her neck, she seems to demonstrate the nature, duration and location of a crime, especially with Conley’s Site Markers nearby.

Tavares Strachan, Broken Windows (Dislocated Remnants), Installation view at Pierogi, 2016.

This thread of minimal gestures referencing violent acts is mirrored across the room in Tavares Strachan’s work: two windows embedded in the gallery wall represent another fiction. Both windows are broken. A tear-shaped hole disrupts the double-layered glass. Shards sit on the sill and litter the ground just beneath the window. It feels artificial, mostly because the glass has been swept too closely to the wall, indicating that the glass was not shattered in situ after the windows were installed. This is a disappointing artificiality. The more exciting artificiality is that the hole as well as the size, shape, and placement of the shards is exactly the same for both windows. Strachan has created Dislocated remnants from simultaneous events, Providence, RI (2010) in a manner reminiscent of Gordon Matta-Clark’s Window Blown Out (1976). Instead of creating the initial marks of destruction, however, Strachan found buildings with windows already broken, recreated panes with the same breaks, and then replaced the existing windows with his own. It is a more ambiguous gesture—replicating the existing disturbance rather than creating, ameliorating, or highlighting it—but again the piece revolves around the nuances of representation and significance of misunderstanding. As the gallery writes, the replaced (or here, simply duplicated) windows do attract fixation whereas a single broken window might not. The gesture of precisely replicating something that is already so clearly dysfunctional is nevertheless potent.

Roxy Paine, Meeting, 2016. Birch, maple, epoxy, apoxie, LED lights, acrylic light diffusers, enamel, lacquer, oil paint, damar varnish, paper, steel, aluminium, stainless steel. 130.25 x 97.5 x 58.5 inches. Images courtesy Roxy Paine, Paul Kasmin Gallery, and Pierogi

After these most cryptic pieces, Roxy Paine’s diorama is a visual and psychological relief. Though undoubtedly complex, the optical illusion of a conference room flooded with fluorescent lights and outfitted with a circle of mismatched chairs also more easily anchors the piece as a site of free association and speculation. The narrative implied here is more bound by the miniature props in the “room,” intricately rendered in sometimes unidentifiable media: cork message boards, half-erased whiteboards, metal coffee dispenser, nested styrofoam cups, and brown-orange rolling chairs. The piece is simply titled Meeting (2016). The writing on the walls—diagramming inability, frustration, Captives and Fugitives, Chance and Fate—suggests that this might be a rehabilitation (or creative writing) session, either just ended or about to begin.

Nadja Bournonville, Medical Machines #7, 2012, Analog C-print, Ed. of 3, A.P. #1/2, 8.75 x 11 inches

The pleasure of defamiliarized and well-constructed objects of domestic or commercial life continues with the final element of the show, Medical Machines, a series of Bournonville’s photographs. In each, a small construction has been made out of elements such as lightbulbs, tape, metal cylinders, and a pressure gauge. Like Peter Fischli and David Weiss’s Sausage Series (Wursterie, 1979), the photographs are about the effects of balance and composition upon quotidian objects. Yet, because Bournonville’s are more static, they reference the language of machines more heavily. Their apparent disutility seems to refuse initial narrative impositions. But, as medical machines rooted in Bournonville’s studies of female hysteria in a Parisian hospital, these constructions are in fact more historically accurately termed “narrative” than any other work in the show. This final inversion of truth marks the success of the show, a full circle of deceit that rightfully ends with assembled invention.