In early 2015, I approached Laura Owens about doing an exhibition of new work at the Wattis Institute. The Wattis, I remember telling her, would be a good context for taking some risks, for trying out a new idea, or even for experimenting with a new approach. Over the year-and-a-half that followed, we spent a lot of time together, over the course of many studio visits, talking about art, talking about painting, and I knew that her ideas would grow organically from there. In the end, she undertook what was surely one of the the most ambitious projects of her career and produced what some might call an “environment” that covered every wall of the main gallery with hand-made wallpaper. Others might call it a single 16-by-150-foot painting that runs across three walls. A sound element was also included, complicating its status even more. Laura, however, called it something else entirely: “Ten Paintings,” even though those “ten” paintings seemed to be nowhere in sight. Ultimately, the exhibition doesn’t only take on the question of “what is a painting,” but also “where is a painting” and “when is a painting.”

I’ll start by taking one step backwards before getting to the Wattis show. What were some of the things that were going on in the studio, or in your thinking, that eventually led to what you did at the Wattis? What was happening that prepared the ground for some of the decisions you ended up making here and things you ended up doing? Are there some previous projects that you feel are relevant to this one, and that played a role in informing your ideas here?

Definitely. I had done a painting for a group show at MoMA [The Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in an Atemporal World, December 14, 2014 – April 5, 2015] where I wanted there to be an audio element. So I inserted small, hidden speakers into the stretcher bars. Clips from a pop song would play randomly, but only three or four times a week, hopefully at a time when the museum was open. But I never really heard from anyone saying they had heard it, and I think a lot of the time it might have just sounded like someone’s cellphone was going off in the gallery or something like that. So it might not have been so obvious. This was my first experiment with an audio component prior to the Wattis show.

But this time, at the Wattis, the sounds were not random, but triggered by people texting the various phone numbers included on the wallpaper. What originally led you to this notion of incorporating sound within a painting? What did that do for you, in terms of making a painting? What did that bring to the picture for you when you first did it?

It wasn’t just the sound but also something hidden that happened some of the time, not all of the time. I didn’t tell the museum that it was in there, and I sealed the speaker in the stretcher bar with a battery life of about four months. A few years earlier, I sent a painting to the Whitney Biennial that had four additional paintings hidden inside it, so the painting itself was like a suitcase for an exhibition that could be unfolded at a later date. For the MoMA exhibition, I also recorded an audio guide at their request, but that audio acted as an extension of the paintings. I recorded myself reading a performative, poetic paragraph that quoted the lyrics of Miley Cyrus and other current Top 40 hits. I also referred to looking at paintings, read the text that appeared in the painting, and asked about reading didactics or taking photos in the museum. It was alluding obliquely to the hidden audio component of the paintings.

Untitled, 2014. Acrylic, oil, Flashe, silkscreen ink, Pantone ink, pastel, paper, and wood on linen, 138 x 104 inches. Courtesy of the artist, Gavin Brown’s enterprise, Sadie Coles HQ, and Galerie Gisela Capitain.

So those are a few examples of ways in which you have incorporated something within or behind or underneath a painting.

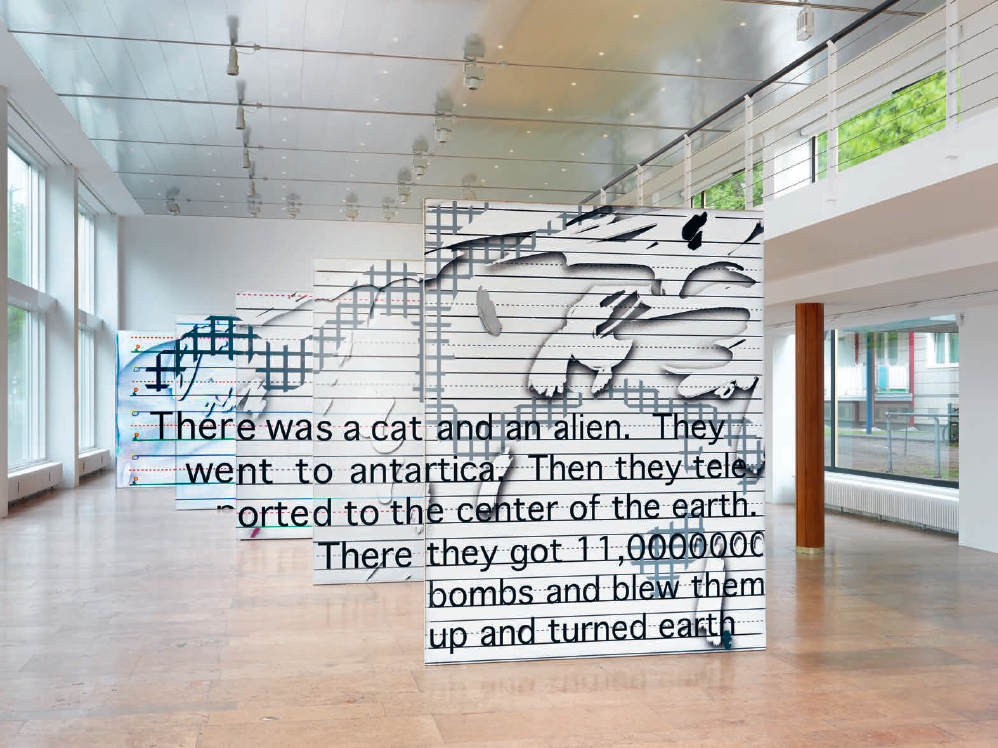

Right. There is another related project I did for a show in Berlin at Capitain Petzel. The gallery is a modernist glass box built in 1964 in the former GDR. There are floor-to-ceiling windows on all four sides, which means that there is not really any wall space to hang work on. Unless you do a sculpture show or something similar, they have to build freestanding walls in the exhibition space. You might not notice walls like these as much in a museum because they typically are built close to ceiling height, but Capitain Petzel’s space is two stories high with a mezzanine, which meant that I couldn’t just hang a painting on one of those walls without it looking like a sculpture. I just couldn’t get my head around these stand-alone walls, so I decided not to use them. The problem had me thinking about an exhibition I’d seen a few years prior by Chris Williams and Mathias Poledna at the Bonner Kunstverein. They had collected all the walls from different institutional exhibitions in the region—all those floating walls—and left them intact with whatever nails or holes or paint color remained from the last exhibition they had been used for. All of the walls were different shades of white, built to different heights, but I don’t think they arranged them in any aesthetic way. It was more like an archive and definitely alluded to Michael Asher’s well-known show at the Santa Monica Museum of Art. Anyway, I didn’t want to use false walls because it would be similar to starting with a sculpture and then hanging a painting on it, so I thought: What if the painting itself is the wall. Over the years I had thought about painting as a wall, linguistically and metaphorically and conceptually. My friend Blake Rayne had the idea that a painter who hangs a painting on a wall is covering the work of the original painter who painted the wall.

Installation view, Laura Owens at Capitain Petzel, Berlin, 2015. Courtesy of the artist and Capitain Petzel.

Installation view, Laura Owens at Capitain Petzel, Berlin, 2015. Courtesy of the artist and Capitain Petzel.

For me, that idea of a painting on a wall being a painting that sits on top of another painting is a really rich one, and has many implications. And I also think it’s an important or useful way to think about what ultimately led to what you’ve done at the Wattis, this idea that painting is something that involves placing a painted object on top of a painted surface that has already been painted by someone else. So you end up hanging a painting on a painting, and the question becomes: How can you incorporate that original painting into your painting? How do you complicate those two paintings?

Right, or how to avoid negating the original painter or act as if their work doesn’t have meaning.

So all of a sudden, the wall itself, as a painted object, becomes a site to think through, as part of an overall history of painting, and this very basic and fundamental relationship between a painting and its wall can emerge as a much more complex and layered one, which I guess is what led to some aspects of the Wattis show, in terms of it being a show of wallpaper—or walls merged with painted paper.

Yeah, then I began to delve into the history of wallpaper. I didn’t in any way become an expert, but I did read that the original reason to use wallpaper was actually just that it was cheaper than having a room painted, and it was used where people rented more often than owning their own home. Whenever there was a new tenant, the landlord would just paper over the walls as a cheap way of renovating. On the other hand, there is simultaneously the history of really fancy, bespoke wallpaper for royalty in Europe, which was unique, similar to a wall mural. This is in the era when Chinese and Japanese art sort of flooded into craft in Europe, and you get some of the most incredible interior decor. Looking at all that, I thought: okay, maybe it is repeating patterns that are interrupted in places, maybe they get painted over. I tried this idea out in a model and thought it looked really claustrophobic. So I just kept revising the design to make a room I wanted to actually be in and not run away from. Early on, I knew I wanted all three walls of the gallery to have the same height, and at that point I saw that I was going to need a lot of wallpaper up there. I tried going over the entire thing with some of the images I was previously using in bits and pieces, an embroidery pattern for example. All the planning is happening in SketchUp and Photoshop to visualize something that I won’t get to see until it’s actually installed, until it’s actually too late to make a real change. When I saw this version in SketchUp, I almost vomited. I was like, “This is way too much, this is so gross, I will not want to be in there, I’ll want to kill myself.” So then I backed away from most imagery I thought I would be interested in based on previous work of mine that was invested in craft or textiles. I backed away from all of that to just start with more simple forms. I scanned a crumpled-up piece of white paper and converted the image into a bit-map with a custom pattern of quarter-inch, half-inch and one-inch squares instead of halftone dots. This gave me a really simple interpretation of those folds and shadows in black and white, which I scaled way up, so one crumpled piece of paper fills each wall. On one wall I ended up ripping the paper, and liked that it was like, “Okay, it’s just literally a piece of paper, wall paper.”

Wall and paper.

I felt intuitively that I had to move away from the more traditional idea of wallpaper.

Two of the things that characterize traditional wallpaper are, like you said, repeated patterns, and then that it’s something that one sends to the printer. It seems like you explicitly chose to go against both of those fundamental characteristics.

Yeah. I knew I would want to make it all in my studio. I thought that would be more fun because I would be able to intervene at any point, like, “Let’s change this up.” I would get more out of the project by making the wallpaper myself rather than sending it out to be printed. I’ve set up a studio that’s kind of like a workshop, so we’re able to handle big projects, but this one really maxed us out.

Installation view, Laura Owens: Ten Paintings at the Wattis Institute for Contemporary Art, San Francisco, 2016. Courtesy of the artist and the Wattis Institute for Contemporary Art.

Untitled (detail), 2016. Acrylic, oil, Flashe, silkscreen inks, charcoal, pastel pencil, graphite, and sand on wallpaper. Courtesy of the artist, Gavin Brown’s enterprise, Sadie Coles HQ, and Galerie Gisela Capitain.

For me, what’s so beautiful is how you’ve made something so simple into something so complicated. It’s this unbelievable amount of work that tries to take very literally the simple questions of what do walls have to do with paper, what do walls have to do with painting, what does paper have to do with painting, and those three words—wall, paper, and painting—are constantly circling around each other—you never know how to exactly use or distinguish them when you describe this piece.

And then the interactive texting comes into play. There are phone numbers included in trompe l’oeil images of classified ads, old emails or just written directly on the wallpaper: “text this number,” “got questions?” “text a question” or I think one says “need a studio?” or something like that, and when people send text messages to those numbers, it triggers audio responses that end up like trompe l’oeil horoscopes. I also integrated your didactic wall text into the work by printing it as part of the wallpaper itself.

I’m also interested in how a site becomes a starting place for you as a way to think about painting. You touched on this earlier when you were talking about the show in Berlin, and how you responded to the fact that the gallery had no permanent walls. You’ve told me that you wouldn’t necessarily describe yourself as a “site specific” artist, but maybe you could talk a bit more about what “site” is for you—because such an important part of the piece at the Wattis is this kind of basic grid structure that exists throughout the wallpaper, which is related to the building itself.

I did look into the site—what was it before. I can’t remember if it was a Greek restaurant or a catering service. And then I looked up Phyllis Wattis, to see if I could use biographical details from her life to start off the project. In the end, I just went with the most simple jumping-off point, the wood beams that hold up the ceiling—and the angled bars that hold up the major beams. I used the placement of those beams to structure the piece and also incorporated images of the beams into the wallpaper by continuing them down the walls in what I think of as a trompe l’oeil moment. It’s like the ceiling becomes part of the piece even though I didn’t touch the ceiling at all. The existing beams become part of the piece.

Somehow the building itself becomes part of this painted environment rather than the other way around. So maybe we can say a few words about the ten paintings. There’s a story you once told me, that I think is useful to bring up here, which is a time when you painted the shadow of a beam onto one of your paintings in a past exhibition. Maybe you can tell us about that moment, what motivated it, and what about it interested you, and how the future life of that painting would be changed, and how a painting’s relationship to a place changes once it’s no longer in that place?

That was a piece I made for a show in London in 1997. I had the idea of making a series of paintings—dawn in New York City, noon in the Midwest and then sunset in LA, with each canvas progressively bigger than the last. It was my first show in England, so I hadn’t been to the space but asked the galleries to send as many pictures as possible along with the floor plan. I saw a pole right in the middle of the space. I also saw just a wall of windows on the opposite side of that pole. Across from the wall of windows, I planned to hang an 8-by-10-foot painting depicting a sunset, albeit pretty abstractly. I imagined the sun setting through those windows and casting a shadow onto my painted sunset. I painted that shadow directly into the painting, so that there was only one place the gallery could hang the work when it arrived in London. The painted shadow looks like a strange stripe of different colors going through the landscape. When the painting left the show and moved through the world, it carried this index of the gallery. I’ve played with similar ideas a lot in my work. At the Wattis for example, the “ten paintings” were hidden within the walls and eventually there will be this other iteration where these 10 panels, which were hidden seamlessly into the installation, come out and become paintings. I was really interested in the idea that you would be looking at paintings without seeing their edges. I had always started a project by asking, “what is a painting, what can a painting be?” But recently, I’ve begun adding the question of “where is a painting?” I think that painting as a medium tries in the most concerted way to deny what it’s about, but there’s so much more that’s going on in a painting that is outside of itself, a painting that dislocates itself into a biography or anecdote, etc.

I think you tested that question beautifully in this particular installation. Another thing that’s interesting, and maybe this relates to the earlier time you’ve done it with this painted shadow, is how site-specificity becomes abstraction. I’m imagining that these ten paintings will be shown somewhere, in the future, but these trompe l’oeil architectural beams, the vertical lines of silkscreened wood grain, fragments of which will appear in these ten paintings, are just going to become abstract compositional marks. They can’t refer to an actual ceiling or to the presence of a larger architectural place, like they did at the Wattis, because that place will no longer be there. So the nature of those vertical lines or horizontal white lines completely changes in terms of what they refer to and how they create a composition for a painting.

That’s true, but with the way photography spreads over the Internet, it might be easy to trace those images back to the Wattis show. But you’re right that on first glance you wouldn’t have this information.

What’s interesting is how it’s not site-specific in the sense that its existence is not determined by the site. It makes use of a place, but also is not completely tied to it. It can completely survive out of its site, but does so according to a different logic—it becomes a different painting once it’s somewhere else. Traditionally, “site-specific art” doesn’t exist outside of its original site—once you remove it from that building it doesn’t really work anymore. You can’t remove a Gordon Matta-Clark from a building. But in your case, a painting can exist in a different site and simply be a different painting.

Even though it’s about place, it’s also about time. The wallpaper at the Wattis definitely existed for a duration of time and then most of it was pretty much destroyed in the de-installation.

Yes, time. If the title of the show is Ten Paintings, not only does one have the question of “where are the paintings” but also “when are the paintings”? Those ten paintings are going to exist at a future date rather than in front of you right now. And then the audio and the text messaging has a whole relationship to time, and the experience of the show changes over time depending on how people are interacting with the phone number. People have been really enjoying that part of the exhibition, of course, and just having lots of fun with it, which actually points to another aspect of your work that we’ve talked a little bit about, which is the role of humor and the importance that humor plays for you and for your understanding of art in general, or painting. I wonder if you can say a few words about that.

I don’t intentionally go out there and do something funny, you know, “Let’s try to be funny,” because that would not be funny at all. Giving myself permission to not be cool, or to do something that’s a little bit embarrassing and allowing myself to go down a path that maybe makes no sense or has no logic just to see if anything about it interests me is just more generative. After a basic version of the audio apparatus was embedded in the painting shown at MoMA, we found out we could control the playback through texting because the device was part of a cellphone. I had ordered a bunch of these audio devices to be hidden inside some stretchers that were possibly going to go to Europe. It somewhat came out of that, but also to keep following the idea and see where it goes. I don’t know, but I think it’s important.

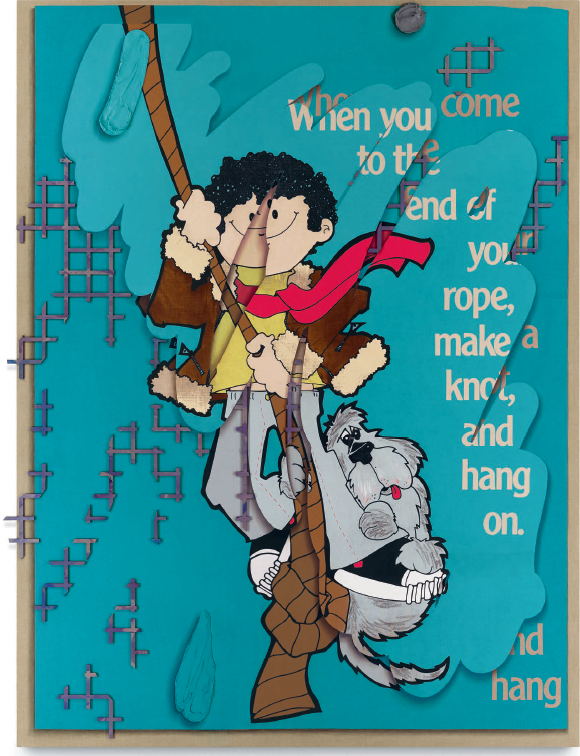

Untitled, 2014. Acrylic, oil, Flashe, and silkscreen ink on linen, 137.5 x 120 inches. Courtesy of the artist, Gavin Brown’s enterprise, Sadie Coles HQ, and Galerie Gisela Capitain.

So many aspects of this piece and of your work in general, I think, places painting alongside the notion of performance, or the performative. I tried to write about this a little bit in my short essay, but I wanted to ask you about it a bit more. Many people have written about that idea, how and when and why is painting a performance, and I think you’re involved in this in a really distinct and specific way. I wonder from your perspective whether those two categories belong alongside each other. Is that a useful pairing or what does that pairing mean to you?

I use the word performance, but I don’t really think of it that way. I know that’s been written about a lot. For me, it’s more a question of where the painting is in the gesture or the story of the events that happened when that particular painting was made—just seeing there are more and more possibilities for how you can look at it. So for me, that MoMA audio guide was part of the work.

So part of the work is in the audio guide, you mean.

Yeah, part of it is in the audio guide and part of the painting is in the hidden sound component. The painting keeps making itself less locatable within the rectangular surface of the canvas, but that literally opens up painting as a much more active medium. But I don’t really like the idea of painting as just this kind of stand-in or prop to signify itself in order for you to think about other things. I am very invested in the idea that what’s within that rectangle has the ability to be a potent, engaging, informative, you know, mind-blowing space. So why not do that also? Just to use it as a marker of a painting . . . it’s already a marker of itself so that’s kind of wimping out, I think.

I think that’s a really good point. You also talked about how a painting is always already art, and is always already a painting, and you don’t really need to do anything to indicate that that rectangle signifies painting and art. In a way, the piece at the Wattis is a single 16-by-150-foot rectangle, and within that rectangle are ten 9-by-7-foot other rectangles, which are the hidden paintings, and within those rectangles are thousands of small black and white rectangles, which are the pixelated markers that make up the image itself. There is a range of rectangles set within rectangles, paintings within paintings.

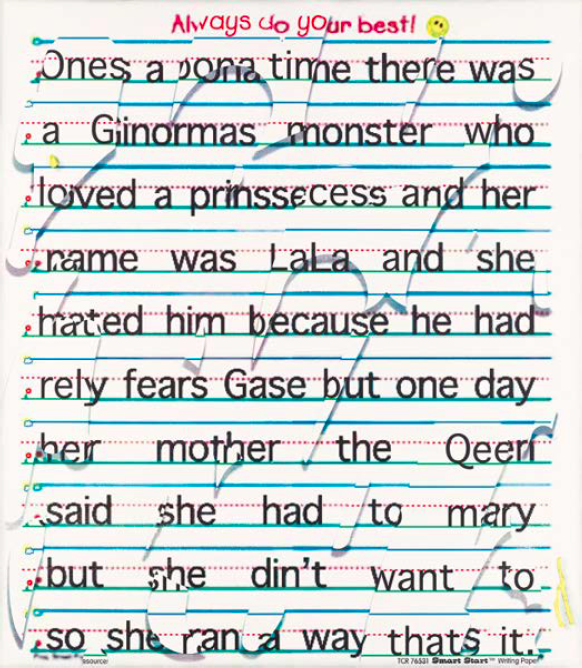

Yeah, and also in the second gallery, showing the embroidery by my grandmother next to some actual paintings is hopefully sort of saying: “Look at these embroideries, can’t you see these as paintings too?” Where do you stop calling something a painting—what does the word mean?

Installation view, Laura Owens: Ten Paintings at the Wattis Institute for Contemporary Art, San Francisco, 2016. Second gallery view, with paintings by Laura Owens and embroideries by Eileen Owens. Courtesy of the artist and the Wattis Institute for Contemporary Art.

And then there’s this whole play on the gendered aspects of the work. For me, that second gallery enforces or puts into relief but flattens out the gendered difference between embroidery and the mural-like scale of the other painting, of how they both are essentially organized according to the same principles and belong together.

That’s cool.

Maybe one last question . . . There are a few things that come up in terms of the resonance of the piece in San Francisco. There is the tradition of mural—this town is lucky to have several very famous Diego Rivera murals, for instance.

Did you go to Coit Tower yet to see that mural?

I haven’t yet, I’ve seen a couple of the other ones.

You’ve got to see it. I think it’s better than the Diego Rivera murals, but you tell me. I don’t know, maybe I’m remembering it wrong. It’s just a small, really specific space. You should go check it out and tell me what you think.

Okay, I will. But it just feels like your piece is not unaware of that context. I wonder whether in addition to looking at the history of wallpaper, whether the mural form is something that plays a role in your thinking here or not.

Yeah, I mean that’s definitely the art I associate with San Francisco. The art that I was first aware of coming out of there in the ’90s—artists like Barry McGee and Margaret Kilgallen. Knowing that they had a totally different aesthetic coming out of both graffiti and commissioned murals, working in a public space. I was aware of that while I was going to art school. I’ve always thought that making a good outdoor mural is one of the hardest projects any artist can take on. It just seems doomed to fail. It so rarely reaches this level of like, “Wow, that’s an amazing artwork.”

That’s funny because I remember you being so interested in how this piece can be seen from the street, and that you were using the façade of the Wattis, which is a wall of windows, in order to make the piece kind of behave like it’s in a public piece. But do so indoors.

Yeah, I was really into what it would look like from outside.