Frieze Art Fair

Regent’s Park, London

October 6 – 9, 2016

When entering the 2016 Frieze art fair, one thinks of 17th-century French Salons. The prestige and influence surrounding the Salons frequented by major art collectors, dealers, curators, and patrons is not unmatched by Frieze. While not as confining, the amount of art displayed at Frieze remained overwhelming (and dauntingly so). With sights including Seventeen Gallery’s virtual reality participants sitting on a massive Ouroboros, an eccentric group consisting of a policeman and a cloaked woman eating lunch together (or performance artists taking a break), and a tent bountiful in hyperbolic personalities, there was plenty to watch at Frieze outside of the art.

First presented in London in 2003, this year’s Frieze London was presented along with Frieze Masters and the Frieze Sculpture park. Frieze London showcases more than 160 galleries along with a non-profit program with emerging artist commissions. This year’s fair also brought with it The Nineties, a new gallery section curated by Nicolas Trembley. This program recreated formative exhibitions from the 1990s, exhibiting works by key change-makers in the arts such as Wolfgang Tillmans and Richard Billingham.

Wolfgang Tillmans, Silvio (U-Bahn), 1992. C-Print, 30.5 x 40.6 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Buchholz, Berlin.

This year, Frieze also collaborated with Autistica, the UK’s leading autism research charity to present “An Infinitely Beautiful Mind,” a discussion which explored the intricacies of the mind and how mental health issues as well as autism can communicate to innovative artistic expression. Other key talks include “Borderlands/The Political” where musician and artist Fatima Al Qadiri, along with others, discussed the hysteria associated with boundaries and the politics of borders and enclosing. With much political tension surrounding the recent Brexit, this also translated over into certain works displayed at Frieze as well, like Victoria Miro Gallery’s choice to include Grayson Perry’s satirically-loaded and embroidered “Britain is Best,” where the rising sun motif—as the sun never sets on the British empire—placed behind a nationalistic group with exaggerated features is not lost on most viewers.

Kurimanzutto Gallery booth, the recipient of the Best Stand Winner

Frieze 2016 played a major role in sanctifying art scenes from major cities such as Los Angeles, Shanghai, and Berlin through the numerous galleries represented at the fair from the respective cities. Mexico City, another area with an emerging arts scene, was well represented by Kurimanzutto Gallery, recipient of the Best Stand Winner. With installation pieces from reclaimed materials by Roman Ondak, Gabriel Orozco, and Leonor Antunes, Kurimanzutto’s cohesive presentation allowed for an important conversation amongst these works, which defy formulaic conventions and inspiring new spontaneous associations with our environment. Across from Hauser and Wirth’s frequented “L’atelier d’artistes” which reimagines an artist’s studio, exploring the cliché and performative aspect of the artist image, Kurimanzutto offers a more subtle infiltration into our immediate surroundings.

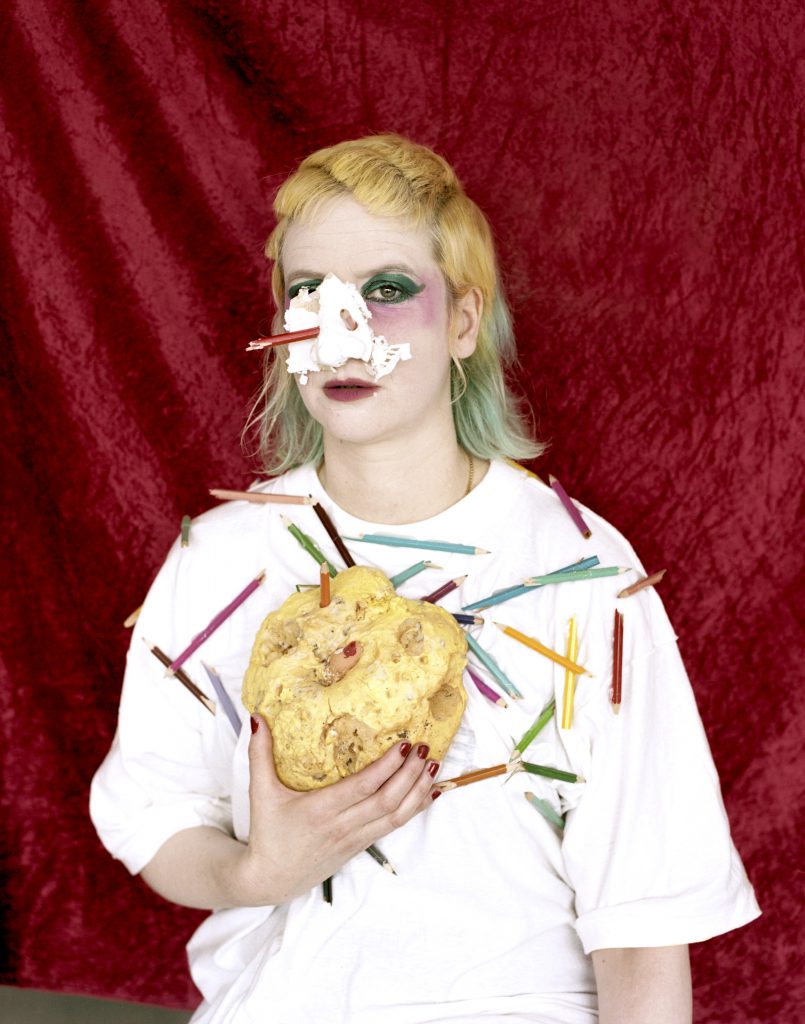

Julie Verhoeven. Photographed by Annie Collinge Courtesy of the artist and Frieze.

On the way to the bathroom, one can find London-based artist Julie Verhoeven challenging gender classifications and questioning the validity of the existence of a contemporary post-gender world in her art intervention as a part of Frieze Projects. A cheekily pink and blue color-blocked carpet leads up to pathways for bathrooms—the pink for the supposed “men’s” bathroom and the blue for the “women’s” bathroom. More prominent than the genital-shaped memorabilia, feces-shaped plush toys, and abundance of tampons, is the presence of the artist, Verhoeven, herself, as a bathroom attendant. Decked out in bright colors and equally animated make-up and expressions, Verhoeven calls attention to herself and her activity in the bathrooms, providing much needed social commentary on the invisible existence of those in the service industry.

Julie Verhoeven Whiskers Between My Legs (still), 2014 Video Courtesy of the artist.

Further into the fair, in the midst of vivacious abstract works in London-based Limoncello Gallery’s booth, was a capricious pair of dice enclosed in a glass cube used by artist Ryan Gander to randomly select works for Limoncello’s collaborative Frieze presentation with Tokyo’s TARO NASU gallery. Entirely up to the fate of a roll of the dice, Gander curated the booth with works by artists ranging from established, known figures like Taizo Kuroda to fresh voices like Alice Browne. A corresponding echo to this display of the esteemed with the emerging was the Frieze Focus program, which displayed younger galleries at the fair. Gander’s practice also allows for a leveling amongst the two and deconstructs hierarchies identified with the art world.

What Frieze really boiled down to was the performative—everything is a performance, from the works, to the people, to the conversations and interactions. It was an elaborate production to be watched watching art, yet simultaneously appreciating the surrounding environment. While social and political context can be stripped away from many loaded works when placed in such a specific and staged setting, contemporary issues still manage to seep in whether actively ignored or brought to surface. As Gander’s curatorial gesture pointed out, art can be as arbitrary as we want it to be.

Latifa Echakhch, La dépossession, 2014. Theater canvas, painting, steel tube and straps. Variable dimensions Courtesy the artist and kamel mennour, Paris.