Making it Online

By Ben Valentine

This column has been pulled from SFAQ print issue 17.

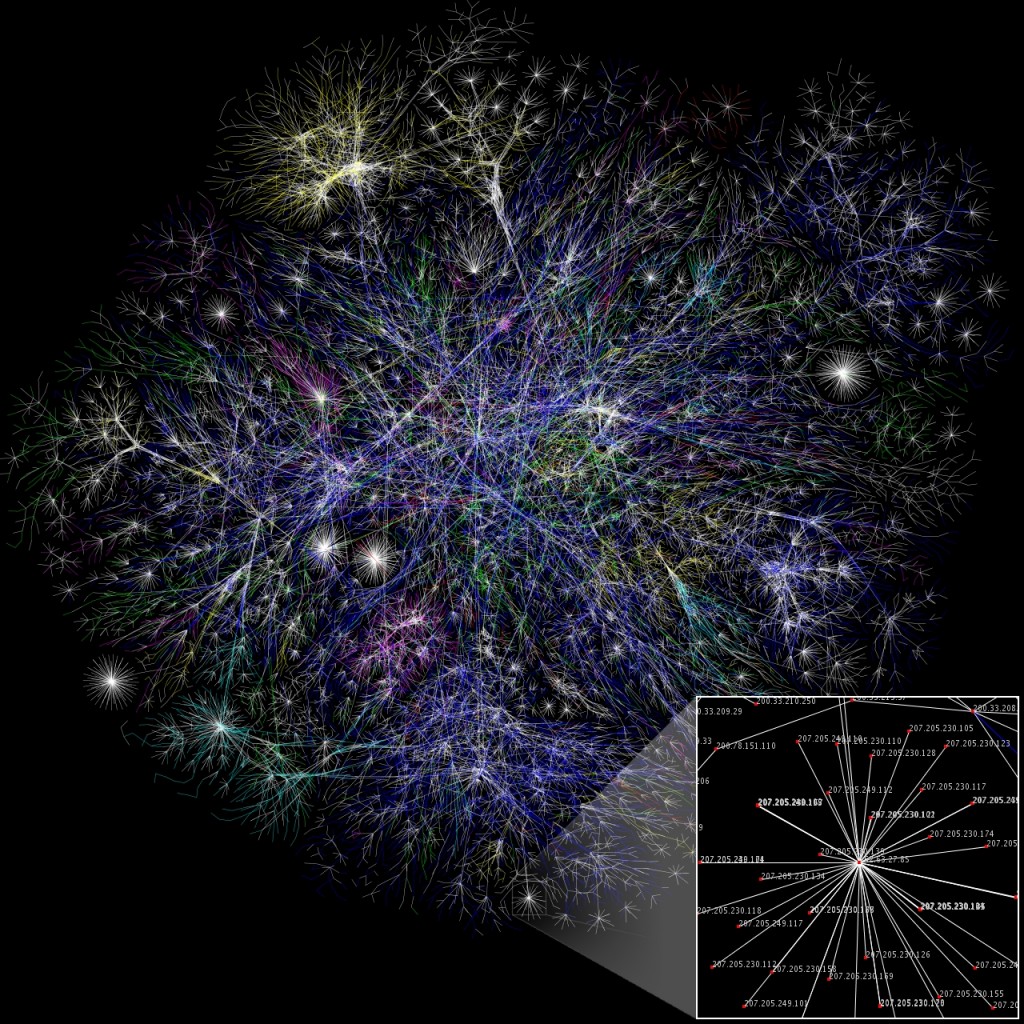

Many hoped that the new connectivity the web offered might radically change the world by elevating everyone’s voice, making all information available everywhere, and that software unbridled by geography and atoms would reshape what’s possible along the information highway. The decentralized nature of the web meant any information—from artwork to dissenting voices—could spread through the network, unstoppable. Surely this would change everything, especially how we create and share together.

Yet now, 25 years after the invention of the web, the Cyberutopianism of its early years is gone. Left in its wake is big data controlled by big businesses, mass surveillance, and monopolized internet service providers. Still, the web has swept over much of the world and now we have millions of daily social media users trying to have fun, collaborate, share, and create online. What, if anything, are we making that is so different than before? How did we get here and where are we going?

Linux and Wikipedia are often lauded as evidence that the net we dreamt of came to be, and for good reason. Although managed and run by a few people at the Wikimedia Foundation, the premise of the site is an encyclopedia created by input from unpaid, anonymous authors who create Wikipedia’s content. As the site says, “There are more than 76,000 active contributors working on more than 31,000,000 articles in 285 languages.” Time after time the largely user-generated website has been proven as reliable as many proprietary and professionally produced encyclopedias, and almost always more up-to-date on contemporary issues.

Internet Map, an Opte Project visualization of routing paths through a portion of the Internet. Courtesy of Wikipedia.

Similarly, the free and open-source software Linux is one of the earliest and greatest examples of GitHub-like production. Although most attributed to Linus Torvalds, Linux and the software it has inspired has involved countless unaffiliated programmers adapting it for their specific needs, or contributing to its core, the Linux kernel. Released in 1991 Linux has experienced great success, and now some variant of Linux is run on 95% of the world’s fastest supercomputers.

The value of these types of open and collaborative super-projects is hard to articulate but vast. Their use of open licensing like GNU and Creative Commons allows for us to build off of one another’s achievements; to collaborate and share work more easily. Just as the scientific community is reliant on open and verifiable tests from which to build, these types of copyleft licenses and the decentralized nature of the web make the efforts invested into these projects valuable for countless people, nonprofits, and businesses in a way proprietary and offline work never could. Yet, these successes are far from the norm; Wikipedia is the only non-profit website to make it in the top 50 most visited websites in the world.

Although there was an unprecedented number of people and work incorporated into open-source and collaborative projects like Wikipedia and Linux, early users wanted much more. Netizens gravitated towards platforms that allowed them to easily publish their own content for their own purposes; we wanted to tell our own stories, make our own art, and run our own projects. Even as professional news publications slowly migrated online, user-generated content grew exponentially faster. Sites that allowed non-technically savvy users a means to easily publish and share skyrocketed, and the rise of web 2.0 saw a staggering adoption of sites like GeoCities, Blogger, LiveJournal, 4chan, and many more.

Enter the meme. While Wikipedia and Linux are prime examples of the web allowing many to co-create one huge project, memes are co-created by many and are subject to constant remixes and reinventions. Although coined in 1976 by evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins, the idea of the meme experienced a resurgence on these chaotic and relatively horizontal online publishing platforms. Memes are the citizens’ advertising.

While countless memes have been made, and most don’t merit any mention, the best and most viral memes are masterful distillations of broad concepts into easily accessible images over a process of remixing. A prime example of this came in 2008, when the seemingly juvenile “Rage Comics” began flooding the image messaging board known as 4chan. While unimpressive at first glance, Rage Comics, as with all successful (viral) memes, are fascinating because of how many people (often strangers) are involved in their making and dissemination, and how quickly they morph into instantly recognizable and precise articulations of complex emotions. While countless were made, the best and most viral Rage Comics remain in wide circulation across many platforms today, six years later.

Memes, unmitigated publishing, forking open code, and wiki-production were the exciting new frontiers of the free web. But with ease of publishing came a reiteration of a very old problem; in an attention economy those who control the systems of production are king. There became so much user-generated content that we wanted filters—we wanted sites to tell us what to look at. What we didn’t fully realize is that those platforms, professionals, and organizations were going to filter content much as they always had: to optimize their profit, not ours. Furthermore, with so much content being thrown into the web, constantly remixed and added onto, the gatekeepers started using secret algorithms outside of our control or understanding. Hardly a perfect horizontal space for the people’s creativity.

Imagine walking into a library looking to find something that really challenges you. You’ve come to feel you need a deeper or different look at a topic, and want something that will push you. Unbeknownst to you, all the books you find first were filtered out specifically for you, based on what you have already read and what your friends read. This is exactly the opposite of why you came to the library, to only find books that supported your beliefs, and reconfirmed your thinking. After much more persistent and dedicated searching, you find that all the books you were really looking for are in the basement way in back and the librarian helping you had been paid to lead you to different books first.

Though hyperbolic, this metaphor reveals how search engines and social feeds like Facebook’s operate, slowly burying or hiding content that might be at odds with your usual reading habits or less profitable to their bottom line. Everything we users are sharing is still online (at least in free or uncensored Internets), but people will have to specifically seek it out to find it. In the mountain of posts we are making, that makes a world of a difference. The illusion that the places where we find our information are neutral is a fallacy, hidden behind the crisp facades of Silicon Valley monoliths. In this way, automated and machine-learning algorithms have come to dramatically shape our making and the cultural experience of what we’ve made in our post-digital world.

What this means for artists, hackers, and outsiders wanting to share their work with the world is that they, much like before the web, have to play the marketing game, and rely largely on publishers and gatekeepers for money to sustain their practices. The horizontality of the web created new spaces for people to gain recognition, but the same economic and social barriers have remained largely intact. Perhaps this is why copyleft projects haven’t gained strong momentum: they aren’t a financially viable option for most people needing to make rent. Even The Commons, Flickr’s service that hosts millions of creative commons licensed photographs which are easy to remix, share, use, and build upon as we wish, is rarely celebrated or used.

Copyleft projects like Flickr’s are being strongly overshadowed by their more overtly corporate platforms. Instagram’s filters can effortlessly improve a snapshot, but always for the benefit of Instagram: each image with a custom filter acts as an ad first to Instagram, then to the photographer. Tumblr, which has done much to encourage net art and virally spread quality photographs through the social web, hasn’t been great for artists’ careers, with much of the work on Tumblr remaining unattributed. This has become part of the nature of the social web. Net-savvy artists get far more views than their offline counterparts, but when it comes to translating a work’s viral success into sustained profit, the difficulties remain. It’s still about who you know, paying for expensive grad schools, being able to take unpaid internships, etc. . . .

A growing body of work by net artists like Ian Aleksander Adam, Parker Ito, or Yung Jake, embrace the aesthetics, designed limitations, and metric-focused attributes of these corporate platforms as a driving force and inspiration for their own practices. These artists create fantastic celebrations and carnivals out of these platforms’ limitations yet rarely produce a meaningful critique. The advertising-focused metrics of these platforms become mirrored in their work; likes, follows, shares, retweets, and more all become a prominent judge of quality. Indeed, critique is far from their goal, opting instead to use these platforms to their logical ends: a like-obsessed and corporate aesthetic accessible to as many people as possible.

While playing within the confines of a canvas has always been the burden of the artist, never before has so much control been exerted by the medium of production onto what is produced as when making on social platforms today. Platforms define the size of the canvas artists have to work with, the palette, the environment within which the work is seen, and much more. When the artwork comes to adopt all the traits and values of the platform that hosts it, what happens when these works experience the same fate as those reliant on Second Life or GeoCities?

Mirroring the metrics of value promoted by the advertising industry doesn’t represent the type of nuance and freedom of expression that is found in the best art. The permanence of our social media profiles and the visible documentation of every interaction (upvote, like, comment, etc.) has created spaces where interaction is effortless, but not necessarily for the deep and nuanced conversations or artworks we crave. The artworks we see in our Facebook feeds are the ones we’re most likely to like, not necessarily the best.

The experience of Context Collapse on these social platforms should be investigated as well. Surveillance from governments, targeted advertising, and of all of our social contexts converging onto one social platform is far from an uninhibited playground for criticality and aesthetic production. Tricia Wang is a tech ethnographer who understands the problems of codifying people through simplistic metrics or finite categories. Wang coined the term Elastic Self to talk about a healthy understanding of identity that takes many layers and forms, given the context. Wang writes on her blog, “Companies and institutions often misinterpret the meaning of people’s social lives, codifying it in a way that forces people into static relationships that don’t reflect the fluid nature of actual relationships.”

Social media theorist Nathan Jurgenson also talks about this problem of confined self-representation on social platforms like Facebook, using the term Liquid Self instead. “Self-expression, when bundled into permanent category boxes,” Jurgenson writes on the Snapchat blog, “has the danger of becoming increasingly constraining and self-restricting.” Jurgenson has celebrated social media platforms like Snapchat for allowing users to explore multiple selves and eschewing real-name requirements, all of which allow for more complex representations and understandings of self. Snapchat’s impermanence then, Jurgenson writes, “introduces the possibility of a profile not as a collection preserved behind glass but something more living, fluid, and always changing.” Can creativity online follow Jurgenson’s ideas to allow for more free, critical, and unencumbered expression? I hope so.

As artists and average netizens become more aware of the impact of the networks around them, more agency in their own production will become increasingly desired. Whether the grip of these networks will loosen remains to be seen. Communities that foster creativity online cannot survive without user support or capitalizing off their users’ works. The question becomes, how long will we tolerate our creative outlets becoming hindered by commercial interests when we refuse to pay to use them? While Snapchat offers an excitingly free space on which to communicate, surely we can recreate much of that freedom in other ways?

The Internet largely operating as an advertising machine doesn’t bode well for a future where anonymous, free, and democratic production can become the norm. While there are many exciting instances of platforms and apps opting out of this model, we need to look at the issue from a macro level, focusing on the infrastructures and laws governing our networked space. Tools like Tor, Whisper, PixelKnot, and many others are made for privacy, but become limited to the users who care. Until we have popular and accessible opportunities that are built with private communication as a side, the alternatives will always be ghost towns.

If they ever move past selling drugs, dark nets could offer an exciting and anonymous community playground, as weird and free as the Internet we wanted. Similarly distributed mesh networks offer an exciting opportunity for community run and owned networks, which could build privacy and localized communication into their core infrastructure. Decentralized peer-to-peer networks such as The Pirate Bay, which is wildly popular, offer a shockingly resilient model to government intervention, and possess many more opportunities outside of pirating music. Social networks like Diaspora and Twister have tried to mimic this distribution model, but have yet to grow in popularity.

Social networks need people to be enjoyable, and much of the exciting productive qualities of a social web are reliant on thousands of users. However, very few users will give up a free network for a secure but paid service. How a functional, free, high quality, secure, and expansive network will take hold in this market remains to be found. We’ve seen a flurry of engineers working to create alternative models in a post-Snowden world; now we need average users to start demanding and flocking to them. If they don’t, we will only see more insidious advertising, more pervasive surveillance, and more hidden control of user experience and production.

Previous contributions by Ben Valentine include: