Who’s Afraid of the New Abstraction?

Alex Bacon in conversation with Jarrett Earnest

*Note: This exchange was printed as a pullout insert in the most recent print edition of SFAQ, issue 17. See below for video interviews with three of the mentioned artists.

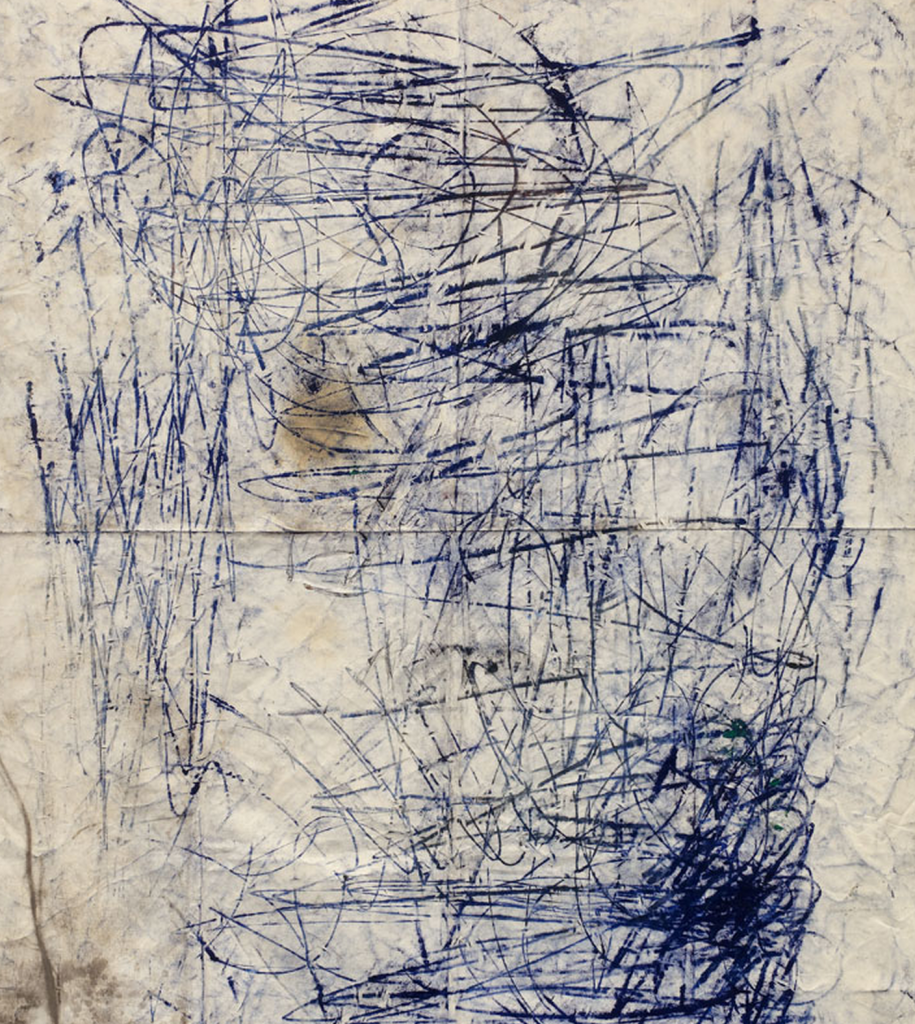

Parker Ito. Courtesy of the Internet.

Alex Bacon is a scholar, curator, and critic who has defended some of those abstract painters celebrated by collectors and maligned by critics—a loose group of young “sensations” called everything from “flip artists,” “crapstractionists,” “opportunists,” to “zombie formalists.” Bacon’s understanding of abstraction is historically grounded, finishing a dissertation on Frank Stella at Princeton, and with the Felix Gonzalez-Torres and Ad Reinhardt Foundations—co-editing with Barbara Rose the recent “Ad Reinhardt Centennial 1913-2013.” He has published long interviews with some of the artists in question, including Jacob Kassay, Sam Moyer, and David Ostrowski. He recently spoke with friend, and crapstraction detractor, Jarrett Earnest about the specific formal qualities of these paintings and the discourses that produce them.

Jarrett Earnest: We’re talking about the type of abstraction being produced now, for the most part, by young, male artists that are usually “minimal,” reflective, slightly scuffed, mass-produced—often with a mediated, re-performed hand—or produced by a glitch in technical processes. The main discussions so far focus on sales and resales, though there have been recent scathing reviews of Lucien Smith in the Village Voice by Christian Viveros-Fauné, Oscar Murillo by Roberta Smith in the New York Times, and a roundup lament by Jerry Saltz called “Zombies on the Walls: Why does so much new abstraction look the same?” in Vulture. I know you have a lot to say in response to all this so could we begin by you laying out some of your ideas and positions? For instance, how do we begin properly talking about these as “abstract paintings?”

Alex Bacon: I want to begin by saying that, while the market certainly plays a significant role in the way contemporary abstract painting has been exhibited, distributed, and received, we must understand that the art and artists are not simply made for and by the market. It is important to separate the formal and intellectual activity of abstract work from the economic activity of a particular segment of the art market, even if we may debate the level to which both are presently imbricated. A few years ago, when many of these artists began working, like most young artists, it was independently of any notion that their work would be shown, let alone bought. It’s crazy to remember that this new speculative market has only existed for the past few years, and that it likely has not yet reached a peak. Further, there are numerous very interesting artists working abstractly today who have not been picked up by the market and, for better or worse, may never be, and this indicates nothing about their relative quality vis-à-vis those who have.

Wade Guyton. Courtesy of the Internet.

In many cases the market selected a certain kind of work, somewhat arbitrarily based on a limited number of largely superficial formal and practical reasons that we don’t need to dwell on too much. Though to my eye many of these selections have been more canny than those that typically emerge from a commercial system. The reasons for the market’s interest in this kind of work include the age-old portability of the easel picture, the open-ended genericism that abstraction has always been charged with, deserved or not, the art historical seal of approval abstract modes have acquired, and tired notions of artistic gesture and authorship, which have been, as I will discuss, largely displaced onto the artist’s conceptual ideas and the labor associated with his or her process. It is also perhaps not surprising, though it should be in 2014, that of the many and diverse artists working abstractly, those who have been picked up by the market are overwhelmingly, though certainly not exclusively, white, straight, and male. This said, the fact that two of the most visible artists in this nexus of abstraction and the market, Lucien Smith and Oscar Murillo, are young men of color is itself a very interesting case.

People like to speak today as if it is the market that paints these paintings, or at least that the artists must be in collusion, or opportunists, when in fact they often have no control or input in the initial decision by a small cabal of wealthy and influential people to speculate on their work. I’m not saying that the artists don’t make money from this system, but that, as with most such systems, it is far less than what is being made off of their creative labor by a select few. Yet the artists are then lambasted as if they were themselves agents of the market, and are stuck with managing, or finding people to help them manage, a fickle and unstable demand of which they themselves are not able to be full participants in, or beneficiaries of. This is not only an unfair double bind, but has obvious relations to larger social and political issues surrounding agency, labor, and access in contemporary Western society.

Parker Ito. Courtesy of the Internet.

The next thing to note is that, to truly understand what is happening today, in the broadest way possible, we must be able to deftly move between considerations of the work’s formal and conceptual operations, to a consideration of why the market might have seized upon work that manifests these characteristics, and then to a consideration of how this in turn might affect the production of such work. Of course all are intertwined and occurring simultaneously but, as the one-dimensional nature of most criticism to date indicates, temporarily establishing these fictive distinctions is the only way to prevent the sociology of the market situation from overriding and totally distorting our ability to understand anything of what this kind of work might be trying to achieve in its own formal and intellectual terms.

For me, the fact that these central elements of the work are drowned out, including the very important and radical issues such work raises, provides us with much to think about in terms of the efficacy of political action, and how discourse and thinking around political issues plays out today. Even to call a system of loosely associated players, who operate at different levels of complicity and coercion, their decisions, and the ramifications of these, etc. “the market” is along the lines of giving a corporation personhood. Both are anthropomorphizing gestures that lend a certain amount of agency and access that is undue to an amorphous system that nevertheless right now finds itself to be, in a Foucaultian sense, a locus whereby power is concentrated and exercised.

For this reason all the critics who simply allow the market to dictate the terms of the conversation become willful participants in the silencing of political activity and discourse, they essentially let the wealthy few who benefit from the market win by accepting their terms as the terms of the conversation. Meanwhile they continue to write pallid defenses of the now empty and academic gestures of third, fourth, fifth generation neo-conceptual, performance, and installation art that finds sanction only within academies and institutions. An issue that is equally problematic, in my eyes. It cannot be so simple an equation as market interest in a certain kind of art means that it is inherently suspect. In certain ways the market may be more visible, vocal, and active than before, but again this has to do with larger socio-economic issues that have, with time, inevitably entered the orbit of art, than the “quality” of the work being produced at the moment.

When Jerry Saltz asks, “why does so much new abstraction look the same?” I respond by asking “why does so much art, period, look the same today?” What are the larger systems that allow for an unprecedentedly large number of artists to share some part of the spotlight and to produce work that emerges from a similar set of precedents, deals with a similar set of issues and, yes, bears superficial formal similarities. A pious refusal of money, which I would point out is not even necessarily a possibility on the part of these young artists who have found their production quite literally annexed by speculators (save full-fledged dropping out of the system, and even then I’m not so sure since artists have concluded production on several of the bodies of work that, at one time or another, drew the interest of speculators), and the work has continued to be traded back and forth, often resulting in market ignorance of the subsequent work made by these artists.

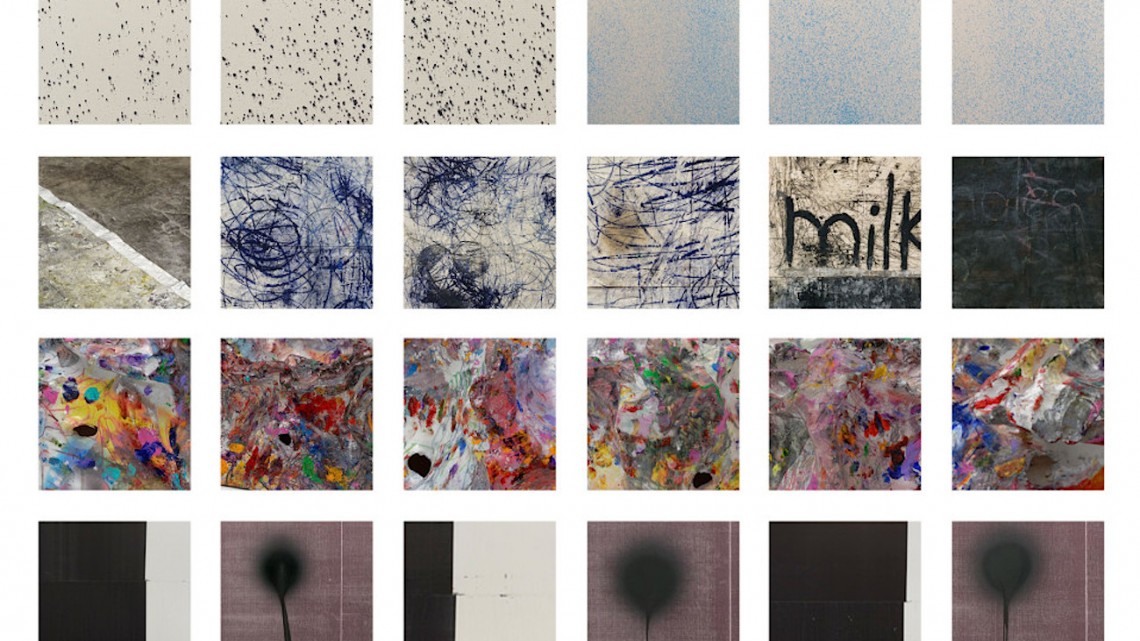

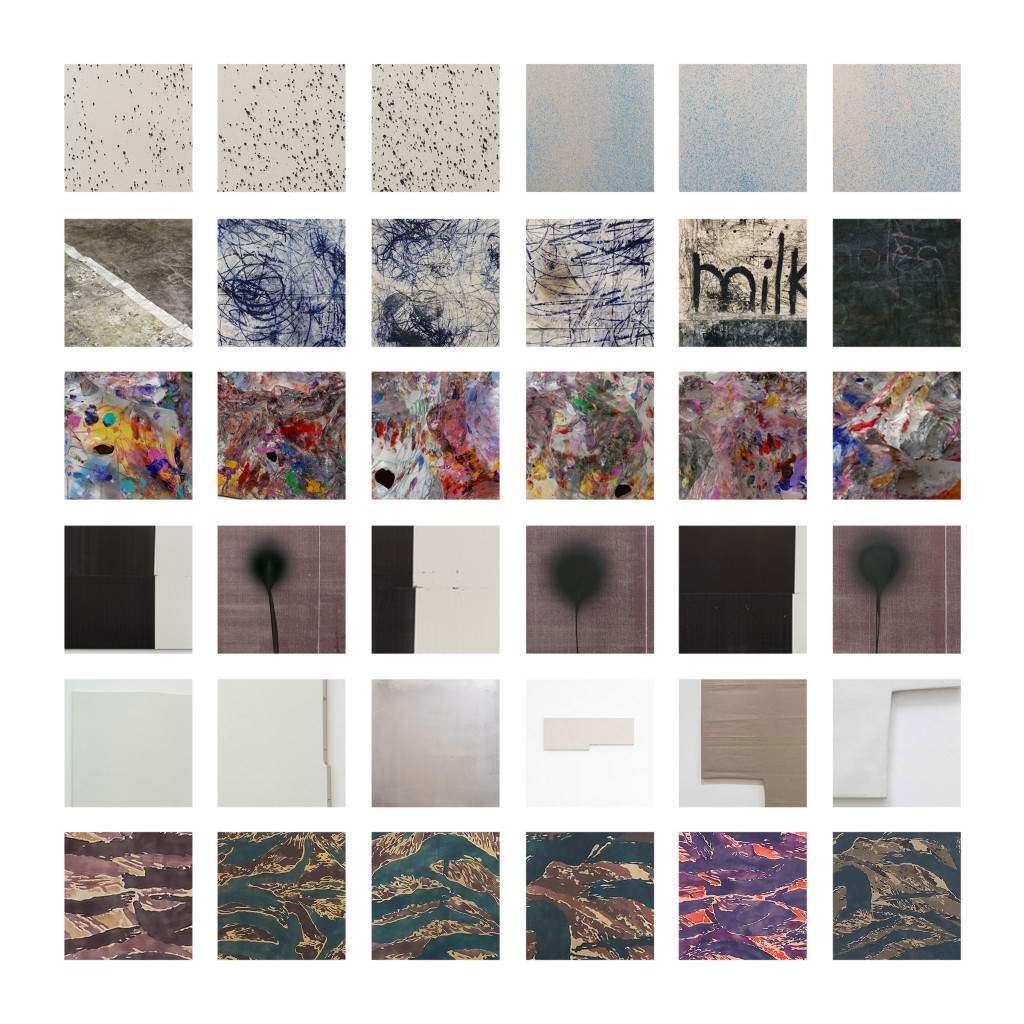

Artists by row, top to bottom:

Lucien Smith, Oscar Murillo, Parker Ito, Wade Guyton, Jacob Kassay, Lucien Smith. Courtesy of the Internet.

It’s debatable whether that will prove to serve these artists well in the long run. I sincerely hope it does, since, while those bodies of work were quite strong, in many cases the newer work is even better. The fact that Wade Guyton printing off numerous additional canvases of a work that went for auction at Christie’s did nothing to stop that painting from setting a record price is just one clear example that today value actually accrues more to methods of hype and distribution—much like special edition sneakers—rather than to old ideas of connoisseurship and the “original.” Today a “collector” wants to own the same things his ten friends do. It’s a status symbol, a register of a certain kind of taste (though more in the sense of hip clothing than of traditional notions of what establishes quality in art), a certain level of economic achievement, and corresponding entry into an “in crowd” who all have the same art portfolio. For critics to hold onto old romantic ideas of the artist as a dignified bohemian nobly toiling away in poverty don’t hold up any longer, and the point is that even if the artist acts in that way it means nothing when his or her work is activated as a product, whose distribution and reception is essentially dictated by the market.

Critics, whether they like or dislike the work formally, should be fighting back against this hijacking of art, by at least taking the terms of the work seriously. People wonder why there is a state of crisis in criticism today, and I find it especially hard to understand given that we have this very visible force to rally against. Given the omnipresence of these same socio-economic forces throughout society we cannot expect that the market hijacking of art will stop at this brand of work; its effects will continue to be felt. In my eyes, this is a much more concrete battle to take on than the formalist ones of the sixties around objects and illusionism that generated so much of our most venerated recent critical past, and whose example really feels like a call to arms amidst today’s critical apathy.

Having now spoken to the market directly in an almost sociological sense, as I think it must be addressed, I would like to tackle the art historical, formal, and conceptual issues at stake in the work itself. It means little to make such charges, as I already have, if the work can still be understood as beyond the pale of defensibility by formal and intellectual standards. Though I must now present another caveat and disclaimer to what I will say, because of how much the market has dictated the conversation around these artists I am hesitant to name names, as it were, and continue to propagate the association of certain artists with the market speculation around their work. Of course, it is only a matter of Googling recent auction results or looking at the charts produced by ArtRank (formerly SellYouLater) to discover which artists have been taken up by the market, and to what degree. Yet to make the association at one level gives credence to the market domination of the discourse around these artists’ work.

I would like to also insist on my feeling that the art must be considered first, and that only after that can we consider why and how the market has seized upon this kind of art. The market likes to categorize the work as “abstract painting” because that gives it an art historical lineage, but in reality the work is not only about so many more things, which I plan to address with you, but, even with regards to art history, it provides a simulation, rather than a loving recapitulation of late modernist non-compositional tropes like process, the grid, and the monochrome. Few of the artists are actually applying paint to canvas so as to actively compose a painting. That idea of painting, the very conception of it that for centuries placed it at the top of both academic and avant-garde hierarchies, still held so much power in the 1960s into the early 1970s that the work of so-called minimal painters like Jo Baer, Brice Marden, and Robert Ryman was based in part on the undoing of that idea of painting’s supremacy.

Today an artist can make anything and painting no longer has any particular weight. If anything it has been humbled now for so many decades that its appearance is always only mediated, contingent, and relational to other practices. For this reason we have to think of the radicality of a group like BMPT (Daniel Buren, Olivier Mosset, Michel Parmentier, and Niele Toroni) and their formation out of the ferment of May ’68 in Paris, even more so than those more often mentioned American painterly deconstructionists.

The primary red herring is process, especially since that is the main moniker that the market has used to identify this assortment of artists. It is true of course to the extent that every artist has a process by which he or she brings an idea into the world, so that it can take the form of a piece of “visual” art. The point, however, is that the way these young artists use process is not in the art historical sense of “process art,” where process was content for artists like Robert Morris, Bruce Nauman, and Richard Serra—you were meant to be able to reconstruct the performative act by which the work was made by looking at the result, the scattered felt, the cast body part, or the flung lead. Today, however, it is a given artist’s exploration of the contemporary terms of materials and labor presented in a “painting” frame.

Many of these artists don’t have a background in painting, and nor do they need to; after all a shallow thing that is hung parallel to the wall has as much to do with digital technology—those shallow objects like tablets, smartphones and flat-screen televisions that serve as vehicles for the delivery of any range of content and imagery—today as it does with painting’s art historical legacy. For artists that are trying to address questions of perception and materials, and even of space, something like painting becomes a useful mode to adopt. Painting here is a tool, much more so than a historical conversation. It is a lens, a frame, a proposition for something that poses as, adopts the form of, etc., a painting.

Earnest: If you make things that ask to be considered in painting history, even though that is not the conversation you are trying to enter, it seems like a failure on the part of form and imagination—what is the purpose of this formal shell game?

Bacon: For Douglas Crimp, the artist Daniel Buren takes the “space of painting,” and that is his radicalism: not presenting “painting” in a specific history, as a next link in the chain, but rather deconstructing the history, exhibition, reception of “painting” itself—that is the legacy that this new work is involved in. When people say these new painters relate to someone like Robert Ryman, it is a distraction from the central issues. Artists like Parker Ito or Michael Manning have been termed post-Internet artists as much as they have been seen in relation to “abstract painting,” and I think it is significant that they have chosen painting as a vehicle to talk about materiality differently—so in their case “painting” is both meaningful and not meaningful. The process these artists use is a means to an end, and that end is often perceptual. That is why post-Internet artists would want to make objects at all—we live in a world now where the image is as important as an object; people encounter everything through images and we give that a reality on par with what we actually see in the world. A lot of this new abstract painting has to do with our weird hybrid perception that exists today, whereby images take on the weight of objects, and vice-versa.

Wade Guyton. Courtesy of the Internet.

Earnest: The emphasis on “process” as a unifying device across these works is part of what makes the visual content inseparable from the larger economic demands that create them—they are about a certain type of production and consumption.

Bacon: As I have been saying, it is important to separate the market activity from the formal activity of the work. I have a lot of strong things to say about the formal aspects, though I am of course not entirely uncritical of the ways some of these artists have, maybe unconsciously, played into market demands of heightened production. We now see some artists producing the number of paintings in a month that Barnet Newman made in a lifetime.. But what that speaks to is not the quality of the work, but the market. The demand is unprecedented, even the most successful artists of the past did not have this level of interest in their work.

To understand the formal activity of the work we have to understand process as a means to an end, though “process” has become for collectors a new form of iconography. For a long time people struggled with how to read abstraction: “What is it about? How do I understand it?” Today I’ve been told, and it seems true, that it is easier to sell this kind of abstraction because people like the fetishized story of the artist’s process—what actually amounts to a lot of banal stuff: this artist had a canvas silver-plated; this artist had this fabric dyed; this artist left this out in the sun. These artists are more like architects or engineers or managers finding experts to help them realize ideas. The majority of one of these artists’ time is not spent putting the gesso on a canvas, but organizing the people who can help him or her execute the work to a certain standard. This has an obvious precedent in the role of fabrication in minimal and conceptual art.

And most of this so-called painting wouldn’t have even stood as painting before; nobody would have looked at the supremely spare surface of a David Ostrowski in the ’60s and said “this is a painting.” They would have said “this is a Dadaist gesture.” It would have had existential connotations. That is why a lot of people didn’t like Yves Klein, because they saw his monochromes as not really “paintings” but as stand-ins for paintings and they felt a lack. Today, of course, the rich, dense surface of a Klein looks uncontroversially like a painting surface. Just as does Ostrowski’s very minimal one.

Jacob Kassay. Courtesy of the Internet.

Earnest: I disagree with you about the idea that there is a formal or intellectual reality of the paintings that are outside of the market forces they are participating in, but seem embedded in the very formal decisions of the work. It is frustrating to read conversations with these artists—like Lucien Smith or Parker Ito—there is no interesting thinking that I can discern.

Bacon: One thing that feels quantifiable about my research into the ’60s is that painting was seen as dying and conservative because the painters didn’t write and speak in the way the object makers did, which negatively impacted their reception. Jo Baer, for one, felt that an artist should not be paid to write, yet she was very articulate and wrote many letters, which we are lucky have now been brought together and published. But her art historical fate has been quite different from those artists, like Robert Morris or Donald Judd, who repeatedly published their very cogent arguments. How much value today is placed on artists being able to articulate their position? It’s unfair to ask artists to be the gatekeepers of the meaning of their work. A lot of these artists are being picked up so young that they aren’t fully formed—we are seeing essentially student work from some of these people, even if sometimes it’s quite good. For many artists I think the best is still to come. But it’s detrimental to have this kind of (over)exposure. These artists have no ability to have an idea and work it out privately over time. Everything is almost immediately put out into the world.

Earnest: Who are the artists in this group you are most interested in and give me a sense of what you find interesting in his or her work.

Bacon: I hesitate to name names, and in doing so perpetuate the associations of certain work with the market. In my own writing I focus solely on the formal and intellectual aspects of the work, since everyone else is busy gossiping about the market. For the most part, rather than simply side-step the question, I’d like to direct people to my essays on, and interviews with, individual artists. But I think, since they have been around for a while , and for this reason clearly emerged from outside the market context that later annexed them, I can discuss Jacob Kassay’s silver paintings. Even more so because I think they are perhaps the strongest work that’s been made in abstract painting in the last decade. They were first conceived in 2005, and then developed for a good three or four years until Jacob first showed them in 2009, then the market took them up around 2010—so there was a good five years in which these paintings evolved outside of any conception of the speculative market that has since derailed our ability to perceive what makes them interesting—the very complex play they have with perception.

Those paintings are really about our expectations of vision—what we see, and our engagement with our own image. People talk about how they absorb their surroundings, but of course they are not mirrors, they are plated silver. You have to burnish the silver to get it reflective and Jacob doesn’t do that, he just takes them as they’re made in the plating process, which gives them very interesting surfaces. Up close the reflection is hazy, but if you go back it gets clearer, and if someone walks by you see them very clearly, while they see themselves as a blur. They are a very concrete commentary on a certain type of perception.

They are about the fragmentary and contingent nature of vision and, insofar as this relates to our forging of identity through the endless stream of images we seamlessly upload and download, they have a contemporary valence. We expect for the Kassay to mirror us back, but instead we are faced with a caesura of vision, a literal blurring out. A Kassay constructs a complex visual system, because you want to move around them to resolve the image, but it’s an impossibility. Nor can the autofocus of a camera map one of these paintings, which is radical considering the sinister potential of technologized forms of spatial mapping and image profiling. The work is not “about” that technology, but it has that valence. That is what minimal-perceptual work is all about: a very concrete perceptual experience, the implications of which are quite far reaching. With Jacob’s silver paintings there’s a lot of food for thought if we allow ourselves to take the time.

Jacob Kassay. Courtesy of the Internet.

Earnest: I think you’re the smartest person defending some of this work—the people advocating for it are generally not doing so in a way that seems nuanced or aesthetically aware—or more accurately the only people advocating for it are doing so with large sums of mute money. How do you see it related to the work you’ve done on mid-20th Century painting?

Bacon: I came to it all from a historical angle. I was someone who had thought he was going to be a contemporary art historian, but then didn’t really like most contemporary art so I moved into the past and dealt with minimalism. Around 2011 I became interested in Kassay and wanted to know more about his work. I was also confused because the abstraction from the midcentury had a lot of critical and academic success but not much mainstream appeal , and here we are talking about the reverse where critics and academics are not interested, but it is popular. Everyday people love to look at these paintings, which is odd considering they would deface Barnett Newmans and Ad Reinhardts in the ’60s. The work touches on a lot of these issues. It deals with image culture, the screen, abstraction in general. What does abstraction mean in a world where images have the same real-world value as objects? Barbara Rose wrote of op art in 1965 that it was the first brand of modernist folk-art, that it spoke to certain ideals around medium specificity and perceptual purity but was packaged in a way that was very appealing to a general audience.

Earnest: The way you described that Kassay made me think about the language around op art.

Bacon: As a historian I see a continuum in the ‘60s around perception in art, spanning the range from Minimalism through to op art, which is the extremely visible end of that continuum. Jacob’s work is certainly more in the lineage of minimal and conceptual art, and even more so the radical interventions of late ‘60s French art, but insofar as I see minimalism as in dialogue with op art, there is that connection with Kassay’s work as well.

Earnest: I see this as “investor identity politics art”—made for and consumed by a highly toxic financial system that thrives on inequality. It completely neutralizes difference in every conceivable way, in terms of gender, race, and class experience—and the most disturbing example has been in strange discussions of Oscar Murillo’s biography. That chocolate factory at David Zwirner was Murillo’s way of trying to navigate that, which most people saw as a failure.

Bacon: It’s unfortunate that people don’t see the actual geopolitical issues involved in Oscar’s work—that his work comes in part from his nomadic, and transnational background. He is engaged in these systems of circulation and migration, so that there are politics around identity, a post-colonial and transnational identity. Yet the market wants to see him as a neo-Basquiat; it loves the highly problematic fantasy of this guy sweeping offices and becoming an art star—that’s very romantic. What is not romantic are the aspects of Oscar’s work that rigorously deal with the movement of very real geopolitical forces.

Earnest: Are we talking about the paintings or the chocolate factory?

Bacon: I don’t think there is a difference with regards to these issues. The fact is that in many cases the paintings aren’t even hung on walls, as often they are laid on floors where people walk on them, or do yoga. Which raises the larger point that for these artists there is not a sense of “Painting,” capital P; it’s not like neo-expressionism where “Painting” returned in its guise as a high art form to reinstate the humanist values the ’60s neo-avant-garde had supposedly stomped to death. That was a battle of post-modernism. Today painting does not have a privileged, hierarchal value for these artists. With Murillo, for example, you don’t understand the paintings without the larger context of the installation-based work he makes, and the socio-political issues from which it emerges.

Throughout the 20th century a lot of work was animated by “responses,” even though this is a false model because there is always more continuity than initially appears. Nevertheless there was a tension the work was establishing with the work of the past, and that is no longer true. We have been living with post-modernism for so long now that it is as if we are born into irony and pastiche, knowing we are already co-opted. There is no longer any resistance or negation, which is what gave rise to self-referential work in the 1960s. It’s really important to understand that a project of someone like Frank Stella—how to make painting an object or purely flat—is not something that plays anymore because the minute something becomes an object it morphs into something else, and then into something else again—there is no fixity. All art has a chameleon status, or should. Today just to get started is hard—painting is then a readymade focal point, a way to get something off the ground.

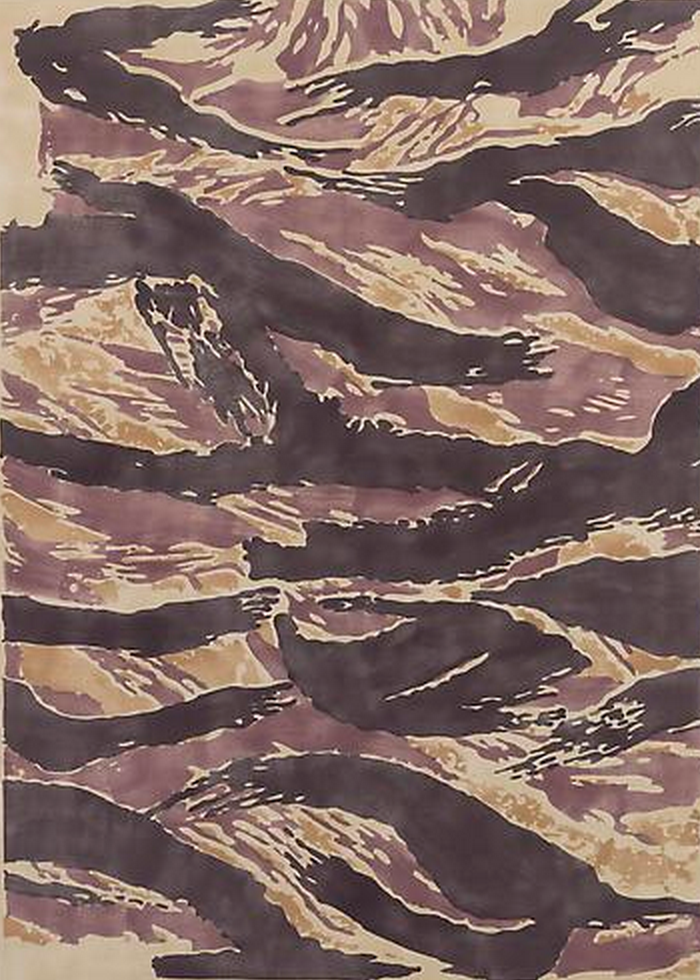

Oscar Murillo. Courtesy of the Internet.

I would like to also raise David Joselit’s idea of “virality”—he basically argues in After Art that in a digital age where work is reproduced and disseminated endlessly that its virality becomes its power; that the more people access and engage with it, the more power it has, and he sees that positively. The market then has its own kind of virality, and that is a way certain people talk about these careers—”oh this artist has the most hits on Instagram so he’s a good buy”— people use virality in a literal sense to see who is financially viable. This raises the question: is this is a critique of Joselit? Is this a bad virality? Or rather, is there a way to use this kind of market interest to unleash some form of critical contagion in the system itself? That is something Felix Gonzalez-Torres talked about when he discussed taking on the forms of established art like minimalism or conceptual art as a gay, Latino immigrant. His point was that if you introduce something within an accepted capsule people will be seduced by it and think it is innocuous, but once they’ve been lulled into complacency you hit them with content. So there is a question: is the only role formalism can play now is as a Trojan horse? And can this be applied to any of the work being made now?

Earnest: Formalism is, and always was, a Trojan horse for content. This moment is defined by the failure of certain forms of critical art practices, most specifically institutional critique and strains of performance. Really smart artists thought they could infiltrate the systems of art and retain agency and make change—I think Andrea Fraser is the best example of this—and as far as I can tell she’s come to the conclusion that the project cannot succeed on its own terms in the face of these crushing systems of corporatization; that they are always already beholden to the forces of advanced capital. I don’t think that is our way to the future. If we cannot infiltrate without becoming beholden, the only option is then to envision, create, open another way of doing it—not in reaction against, but away from—together.

Lucien Smith. Courtesy of the Internet.

Bacon: But look at the recent Christie’s sale of Wade Guyton. He started Instagramming photos of him reprinting the painting that was in the sale, printing it off, printing it off. Some critics happily talked about him subverting his own market. The painting still went for a record price, proving that these collectors do not want a “unique original”—they would prefer that there were fifteen of them than just one. It’s not about these collectors being connoisseurs, it’s not “I own the best painting.” It’s about “I own the same painting that all my friends own.”

Earnest: It’s human beings making decisions about these things. And artists and critics and curators have thrown up their hands like they aren’t responsible for what “the market” is doing. You can decide to make something that doesn’t make itself available to circulate in the way those things do, you can decided what conversation you are having and where you are having it. I’m conflicted about even having this conversation because I feel like our power is to choose not to talk about those collectors, those investors, in favor of things that we can focus on that are more worth our time because they can open onto another future.

I was just reading an interview with Judith Butler talking about Israel/Palestine and finding a solution of cohabitation—an idea that is full of potential antagonism and discomfort, and that many people say is impossible, but she says she believes it is the purpose of philosophy or theory to envision and hold open such spaces; that nothing radical could happen that was not kept alive and open. That’s what I think art does, too. Maybe some of the exact formal things I’m so critical of in these young crapstractionists I would be in favor of in a different climate, with a different discursive charge. But as it is, it seems completely disengaged from the struggle and it’s hard for me to not see it as cynical opportunism—I think Christian Viveros-Fauné calling them “the Opportunist Brigade” is probably the best name, although I use “crapstraction” because it’s sillier.

Bacon: In terms of cynicism, you can’t put that on the artists. I can’t think of an artist who makes work from that position. Sure, there must be a link between this work and this kind of speculation because they emerged at the same moment, but what “the market” has done is become a player, a player in a way that critics and curators are not; and the way people talk about this is as if “the market” is making the paintings. But it still needs artists to make the work. Maybe there are these market constructions of a “Lucien Smith” or a “Parker Ito,” but there are the actual artists too, and in a way they have equal validity. Isn’t that what Guy Debord said, that spectacle is so much capital concentrated that it becomes image? There is so much capital concentrated in certain artworks that the market’s vision of those artworks becomes its own parallel reality, entirely separate from the very real actors involved in making the work—the artists. Intelligent people today shouldn’t allow that to become the only functional reality for this kind of work.

*Note: This article was originally printed with degraded and unauthorized images from the Internet. All contacted galleries declined SFAQ’s permissions requests—a perfect illustration of the ways commercial interests aim to control discourse about their properties, especially within this context of market speculation.