Helen Rebekah Garber, Numbers

Eva Schlegel, Solo Exhibition

Gallery Wendi Norris

161 Jessie Street, San Francisco, CA 94105

06 November 2014 – 09 January 2015

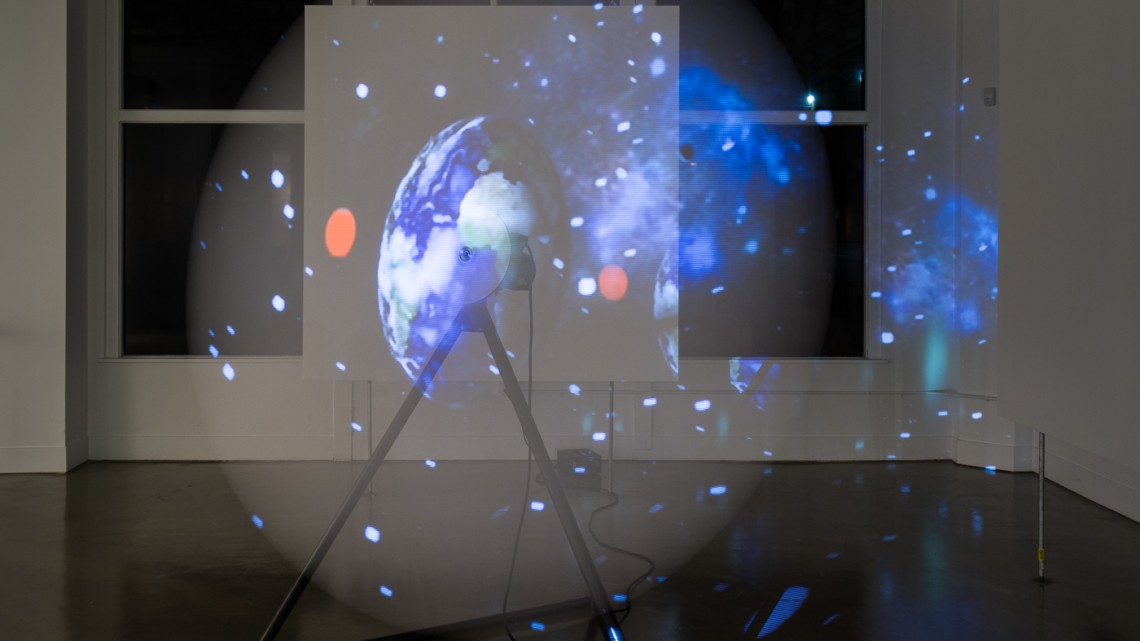

The lights are dim in the gallery and a somewhat loud, mechanical hum fills the space. To the right of the entrance is an 8-foot-diameter rotor of spinning fan blades that creates a round, slightly flickering surface. Though the sound emanating from it clearly indicates its power, the piece surprisingly does not produce any wind. The round surface of the rotor has a planetary innuendo, which reiterates the themes of the two intermittent films by Eva Schlegel that are projected onto the blades, titled No Man’s Heaven and Rotor Universe. A stanchion surrounds the spinning sculpture-cum-movie-screen to prevent people from coming too close. The piece dazzles from the prescribed viewing distance, and the desire to touch it, to see how it works and to be a part of it is overwhelming. Looking from a farther distance, portions of the film spill beyond the rotor boundaries onto two panels behind it, adding multiple layers and shifts of perception.

In No Man’s Heaven images of people wearing business attire float into view as if in free fall. You look directly up at them from the ground, yet the rotor is installed perpendicularly, so logically one knows that they are facing the work, but there is a distortion of both time and place. Schlegel is interested in the phenomenon of what it is like to inhabit and navigate the lack of gravity in space. She took photographs of professional body flyers in Zurich for the imagery. The business attire the subjects are wearing alludes to modern capitalist dilemmas such as stock market crashes, or the trauma of failure. Any numbers of other readings are also evident, such as 9/11 or perhaps the more morbid suicide—if it were not for the calm, focused, and at-ease expressions of the falling figures. Using text documentation from European, Russian, and American astronauts, phrases whirl in the rotor, sometimes superimposed over the figures, and sometimes on a stark white background. In some instances the large text is bowed, as if it were projected onto a glass ball, while in other cases the text spins like a pinwheel from the center out: “To begin with, you felt like you always want to hang onto something.” By using actual testimonial and subjects wearing everyday clothes, Schlegel is conceptually inviting the viewer to imagine themselves in the feeling of weightlessness: “It wasn´t just me falling, but everything was falling, which gave me an even a more unsettling feeling . . .”

Eva Schlegel, “No Man’s Heaven,” 2014. Rotor, video projection 94 inches (240 cm) diameter; 300 rpm (Running time 8 minutes). Installation photos Johnna Arnold. Courtesy of Eve Schlegel and Gallery Wendi Norris.

In the other film, Rotor Universe, an artificially constructed universe rotates and spills onto the peripheral space of the gallery, creating an expansive and fragmented perspective. Here, Schlegel posits that existing in space is something to consider, but the only way to achieve that is to offer a visual alternative for where physical existence is simply impossible. Red flashes of Morse code translate a phrase by NASA astronaut Edgar Mitchell:

. . . that planets are just that, they are planets and you are not connected to anything anymore . . .

The quote reiterates the inaccessibility of the planets themselves, and their inhabitability. The etymology of the word “planet” is from the Greek planētēs, from asteres planetai meaning “wandering stars,” from planasthai meaning “to wander.” The double entendre insinuates both the wandering of the planets themselves and the wanderlust that seems to be an inherent activity for humans—our curiosity for attaining a tangible relationship with something as far reaching as planets only adds to the sublime nature of the night sky.

Also in the room by Schlegel are two other bodies of work, one comprised of appropriated images form a Viennese brothel, and the other a series of blurred female figures near doors and windows. The former features figures in coital positions, while the latter series features women in lingerie or slightly clothed, as if waiting for a lover to arrive. In all three of Schlegel’s series—the planetary works, the pornography, and the women—a common thread of the body reacting to space prevails. Whether as subjects of sex work or as impossibly cascading forms, commonplace activities are made apparent through distortions reminiscent of dreams or science fiction, yet reality lingers.

(left) Eva Schlegel, “Untitled (031),” 2013. Lambda print 63 x 47 inches (160 x 120 cm). Edition 2/3 + 1AP.

(right) “Untitled (153a),” 2014. Lambda print 81 x 41 inches (205 x 105). Edition 3/3 + 1AP.

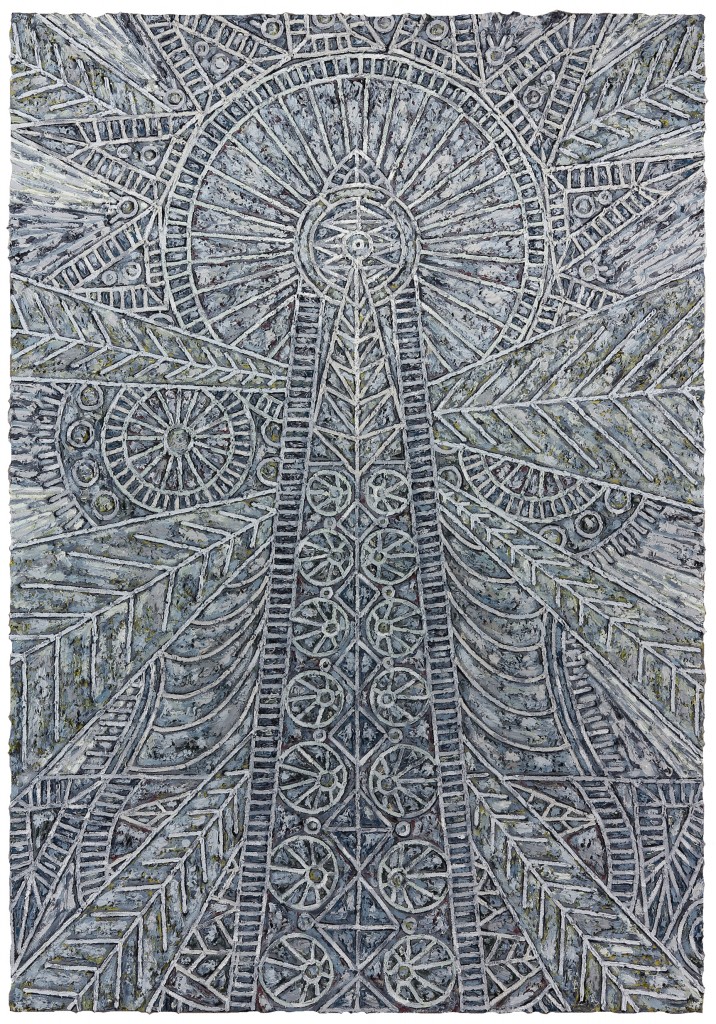

Also presented in the gallery are two bodies of work by Helen Rebekah Garber. One is a series of large-scale, impasto, pale-colored oil paintings, and the other is a series of three diptychs. Garber emphasizes the abstraction of language by creating alphabets that are comprised of geometric, modernist shapes such as circles and squares in varying degrees of thicknesses that span the surface. The letters she creates are inspired by Sir Thomas More’s utopian alphabet created in 1516 and featured in his book Utopia. Through her rigorous study of civilizations’ use of language in addition to obscure or occult culture, such as the writings of Aleister Crowley and the Qabalah, Garber deconstructs symbols and reassemble them to create new contemporary meanings. As the press release states, the series grapples with the “intrinsic truths about human communication.” But at the same time her work addresses concerns of impermanence and the intricate delicacy of symbols.

Helen Rebekah Garber, installation view. Installation photos Johnna Arnold. Courtesy of Helen Rebekah Garber and Gallery Wendi Norris.

Although all of her work clearly uses symbols, the paintings are by far testaments to her research into the phenomenology of language. Each piece is layered with almost 1/4 inch oil paint repeatedly applied in layers over the configurations of complex patterns. From a distance, the pieces appear as soft, gray-blue fields striated with delicate pale lines. Up close, many colors peak through from behind the steely surfaces—pinks, yellows, blues. In general, Garber focuses on sacred geometry with these works and the titles give the viewer clues to her thought process and her conceptual underpinnings rooted in religious or mystical iconography. For example, Katholicon for P. references buildings that are found in Eastern Orthodox religions.

Helen Rebekah Garber, “Mars in Place of the Ideograph,” 2014. Oil on linen. 72 x 50 inches (182.9 x 127 cm). Courtesy of Helen Rebakah Garber and Gallery Wendi Norris.

Knowing that Garber studied Crowley, Mars in the Place of Ideograph seems to have a direct correlation with his writings on the planetary relationships that influence and steer interpretations of how one locates themselves and navigates the world. These navigations are in correlation with a linear path of orientation fixed in the Qabalah. Where a point begins a sequence of events, for example, it leads to a second place in the creation of a line, that lead to planes, then to a solid which forms matter, leading to motion, thereby prompting time. From there, the past, present, and future are laid out, followed by being, thought, and, finally, bliss. This linear path is synonymous with the concept of mark making and perhaps the existential and dare-said transcendental equivalent of art making itself. In viewing these works, Jay DeFeo comes to mind. Her work, too, is noted for its pensive and repeating paths that follow lines on the two-dimensional plane as well as building up in three-dimensional form. DeFeo’s history is noted with a sentiment that borders on obsessive dedication to one particular thought. So too does Garber dedicate herself to building these paintings up within the framework of very specific lines and shapes. To cite Crowley, from “Nothingness a Something which can be said to exist.” In this way, both DeFeo’s and Garber’s work taps into concepts of nothingness. From that nothing, a point can arise, and so on goes the cycle.

Helen Rebekah Garber, “Katholikon for P.,”

2014. Oil on linen. 60 x 60 inches. Courtesy of Helen Rebakah Garber and Gallery Wendi Norris.

Though Schlegel and Garber seem disparately paired, upon close inspection the work is very much related in ways that require longer looking and a spell of background research. The gallery will be closed for the holidays between December 21 and January 1 and will reopen on January 2. The exhibition closes on January 9.