I first found out about Pedro Reyes’s project the People’s United Nations (pUN) while attending the 2013 Creative Time Summit in New York. There was a booth in the auditorium there for recruiting individuals from all over the world to represent their homeland as part of the exhibition at the Queens Museum, the site where the UN General Assembly met from 1946 through 1950. The People’s United Nations congregated its 150 citizen-delegates for two days in late November of last year.

Reyes’ contribution at the Creative Time Summit was the organization of conversations between himself and former Bogotá mayor Antanas Mockus Šivickas, who famously introduced mimes to curb traffic accidents in Bogotá, as well as numerous other political endeavors that took cues from art and creative impulses in general. The conversation was entitled “The Absurd and Urban Transformation,” and successfully brought genuine curiosity and playfulness to the very dry bureaucratic problem of tax collection. The conversation culminated with the two of them offering tokens of public resources in the form of sacramental bread to the mouths of audience members.

Long an admirer of Pedro’s ethics in the form of art projects inspired by psychotherapy, I was now a follower of his aesthetics, which I perceived to be adorations to humanity and the complexities of human psychology and spirituality. The following freeform interview is an attempt to understand the mechanisms behind his therapeutic thought process.

Can you tell us how you originally came up with the idea for People’s United Nations?

The dream of making a parallel organization to the UN may be something that I thought since I was a child. I used to read Mafalda, which was a very influential cartoon for several generations in Latin America. Different from Charlie Brown (Peanuts), Mafalda was always commenting on the Vietnam War, the tensions between the Pentagon and the Kremlin, or the dictatorships in Latin America. Her dream was to grow up to become an interpreter at the UN to smooth the exchanges between countries. Many years later I got invited by Larissa Harris to present a project for the reopening of the Queens Museum. The building was the first home of the UN and where many historical events, such as the partitions of Palestine, and North and South Korea were discussed. Two other factors were crucial: the Queens Museum has a special vocation for social practice with a unique community outreach, and Queens is perhaps the most ethnically diverse place on Earth.

Your work is political, in a direct sense, and yet it seems to work precisely because it is not overtly political. It is transformational rather than political. Can you say something about the positive outcome you hope for with much of your work, especially your project People’s United Nations?

We live in a world where different cultural environments overlap as in a kind of palimpsest. Each cultural environment has its own set of parameters to assign value. My work in general is very optimistic and Panglossian, as in the character from Voltaire’s Candide. It suggests optimism regardless of circumstances, and is very utopian. Dr. Pangloss is someone who speaks all languages with all species, the Latin pan for everything, all, and glossa for a list of words; glossary. People’s United Nations is a totally Panglossian project in the sense that it aims to bring everyone together—one representative from every country in the actual UN. Humor is a very important aspect of all of this. One of the main theses of my work has to do with humor and the way that jokes work. Most jokes have a setup and a punch line. The setup involves something that is wrong or is going in the wrong direction. To tell a joke is a process of things becoming an awkward situation, and the punch line is this shocking delivery far below your expectations. And when something is far below your expectations, when someone is in a ridiculous and embarrassing situation, the way one can best handle such shock and disappointment is with laughter. For instance there is a joke where a guy goes to a doctor and the doctor says to the patient, “Here is your analysis and it says that there is not much time left, only ten.” The patient replies anxiously, “Ten months? Ten weeks? Ten days?” And the doctor says, “No . . . 10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5 . . .”—you know? You have to have a setup that is a kind of warning and a delivery that is between your expectations of reality and the realpolitik. The way that a joke allows one to deal with disappointment is through laughing. According to biologists, laughing is a kind of reaction where, say, you thought you were being attacked but you realized it was a false alarm, and then a scream is produced that is this kind of a spastic thing that we call laughter.

What I am trying to do with pieces like p(UN) is reverse the mechanisms of jokes. So you have an extremely optimistic punch line, something that is so far above your expectations that the shock value is a resolution that is extremely, hilariously optimistic. I do that because I believe that the shock value of optimistic projects is something that brings new ideas to life. It is a little bit messianic, but it is based in spontaneity.

In his book on the psychology of jokes and laughter, Freud says that jokes produce revelations through their technique—creating something that makes sense via the mechanisms of the nonsensical, juxtaposing two conflicting ideas—and in this way jokes are akin to how our unconscious mechanisms make sense in dream displacement, allowing for new interpretations to arise. Can you say something about the thought process of conflict resolution in p(UN)? You say that diplomacy has proved not to work, so you want to try alternative play therapies.

For instance, one of the workshops at p(UN) consists of breaking down the participants in groups of five or six, and then for the first ten minutes everyone has to share the most embarrassing thing about their own country. Then the participants have a workshop where they envision an ideal world where, if they were to open the pages of a newspaper, they are to imagine the polarities were switched around from the worst to the best. For instance, people who were from the Philippines were angry that the Catholic Church had ruined the reproductive rights of women. So then they were able to imagine a joint venture between the Catholic Church and the State to open abortion clinics nationwide, and they expressed this idea though the workshops. Another example emerged when the people of Turkey were embarrassed that they had the highest number of journalists in prison. The reversal of that fact was that Turkish prisons could become journalistic meccas and that a newspaper called the Turkish Prison Times would sweep the Pulitzers. Because really it’s not that farfetched; it’s actually a completely plausible idea. Imagine that you create some kind of network inside a Turkish prison that becomes an online newspaper through which they smuggle their texts. It really could be!

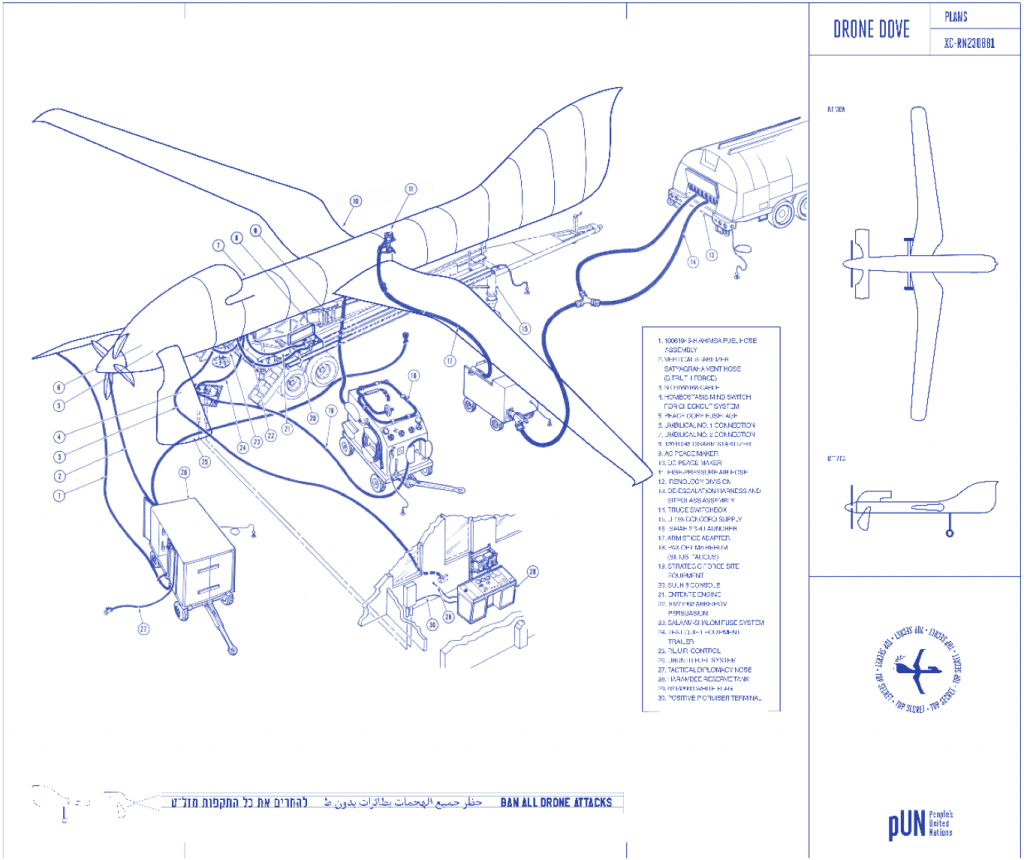

What I’m trying to do comes from this basic thing that I believe in, that there are two ways to deal with reality. One is to focus on the problem, and the other is to focus on the solution. But the focus on the solution has to be something that is daring. And I do that in sculpture as well. With Disarm and Imagine, a continuation of my project Palas por Pistolas, I transformed seized guns into musical instruments. Turning a machine gun into an electric guitar is a successful, positive transformation. Many of the operations that are underlying my work are basically quite systematic in the sense of identifying an agent of suffering and death and destruction and making a change in polarity where these agents become something extremely positive. For instance, I may do a collage where I turn a tank into kind of a musical-mechanical orchestra on wheels, or I take a drone and I turn it into a dove, and it becomes a drone-dove. Visualizing something positive is a stepping-stone towards that reality. You have to have a vision.

Blueprint plans for Drone Dove, 2013. Courtesy of the artist.

Disarm, 2013. Instruments made from de-commissioned weapons, Lisson Gallery, London, 2013. Courtesy of the artist and Lisson Gallery, London.

Imagine, 2012. Documentation of fabricating a musical instrument out of a destroyed weapon. Courtesy of the artist.

It would seem to me that a concentration of yours is to play with the given polarities of a situation. With projects such as Disarm and Imagine you have made a pretty straightforward reversal of polarities, from this extremely negative force of the weapons to this very positive source of the musical instruments. However, it’s a great deal more nuanced with something like People’s United Nations, where the act is not necessarily reversing or transforming a given situation, that of the UN, but rather presenting viable resolutions that could easily be implanted by the already existing state of affairs. Nonetheless, there is a visceral reaction to the solutions offered through p(UN), such as the absurd and hilarious ones you have mentioned with the delegates of the Philippines or Turkey. Why do we have this internalized reaction to these great solutions that says, “that’s clever, but it’s totally crazy, too crazy to work”?

I believe it is because the status quo is insane by nature, how things operate normally is often wrong from the very get-go. What we are used to accepting as normal is in fact insanity. It’s why R.D. Laing would say something along the lines of “perfectly normal people have killed two million people in the last century.” The idea is that you are never going to run out of incredibly wrong things in the world that need to be corrected. They’re everywhere, from energy for communication, or distribution of wealth, everything is wrong.

For instance, food, when I was doing the catering for People’s United Nations, I wanted to do a kind of prototype dish that could become the staple food for the future, and my rationale for doing this turned into the “GrassWhopper,” which is a hamburger of crickets, of grasshoppers, and if you stick to the most rational solution, this is it! The GrassWhopper is the most kosher thing to grow in this way, because insects such as crickets don’t need refrigeration, and they are pure protein, and no suffering is involved. If a cricket eats 100 grams of grass it becomes 100 grams of protein in its body so it’s a kind of 1:1 translation, whereas a cow has to eat the equivalent of hundreds of football fields to create a single pound of meat. There are so many aspects to illustrate how this food choice is in fact the most rational, economical choice of all. It may look exotic and strange, but that’s only because our regular world is wrong and completely upside down.

The Grasswhopper, 2013. Courtesy of the artist.

Intuitively we laugh at the GrassWhopper and jump a bit because it sounds disgusting and absurd to our usual sensibilities. However, if you were a super-rigid bureaucrat crunching the data, it would be something where to see this on paper it would be the most pragmatic food solution.

One of the things that art does best is to bring estrangement. You have to make the familiar strange in order to reveal the arbitrary standards that we live inside of. And you have to make the strange familiar to introduce something new. Monotony is gray. Art brings color, and when it punctures the monotony of the everyday, it creates estrangement. In order to do this you must make the strange familiar and the familiar strange.

This idea of estrangement is really interesting in the context of People’s United Nations because it seems to be at odds with the espoused mission of the actual United Nations. What I imagine is that the United Nations seeks to be seen in the public imagination as bringing people together to create a common understanding and set of solutions, and in this way presents itself as diametrically opposed to estrangement. So then, the artistic component of p(UN) would seemingly go against that logical, rational, practical ideal of the actual United Nations. I’m trying to contextualize the idea of estrangement within the kind of cultural politics that play out at the UN that supposes a goal of “mutual understanding” and “democracy.”

But what makes it work has to do with it being not only estrangement; it’s also role-play. Estrangement is one condition present but the reason these individuals felt like they needed to be there, the reason people were so committed to the project, was because of the aspect of role-play, and playing a part that is already inside of them. I was afraid the volunteers would not show up, because this was in New York where people’s time is very coveted, and especially since it was freezing and all the way up at the end of the 7 line in Queens. It was a big request for people to do this for free. But in the end they not only showed up for the first day but they came enthusiastically for the second because they were passionate about it. They really devoted two whole days to this, and these people were all very busy people, important people in their respective fields. I really believe that the reason why they committed was because of the aspect of role-play. The moment that they accepted their roles as delegates, they would fail their countries if they failed to be there. Their countries would not be represented. So they had an honor and a duty to—

Their identity. Twice removed, and put back again.

Yes, helped by the fact that they were wearing a badge. I believe a lot in the rich role of props. So they were asked to dress in business attire or their ethnic clothing, just as in the UN, and also they were wearing a badge with their flag and their name. If these same people were just at a party it would be different, but the fact that they became delegates created a kind of atmosphere of respect and admiration for each other, and it was all because of role-play. Estrangement is just a kind of substrata; it is this role-play that brings a certain cohesion to the psychodynamic.

In some way this role-play becomes a dress-up game where someone becomes themselves again, albeit in the role of their entire country. But of course they were not alone. You have people in character talking to other people in character but the character is themselves.

In New York everyone is from everywhere, but during p(UN) they were delegates and they were talking on behalf of their nations and their legacies and their cultures. They had to advertise and advocate for their countries. They took it very seriously because they were around others doing the same, which set up opposition that would not exist on the streets of NYC normally. As for coming together with the other delegates in new ways there was a therapist from the school of Milton Erickson doing couple’s therapy, and I had these people from different countries going to this couples therapy and really talking about their long-standing hatred between their two countries to this therapist. There were many other situations where there was socio-drama. I use a lot of psychology, mainly Milton Erickson and Jacob Levy Moreno, founder of psychodrama and socio-drama.

Citizen-delegates and other participants of The People’s United Nations (pUN), Drone Dove in foreground and official pUN flag with motto “Hands-on with a vision” in background. Queens Museum, New York City, 2013. Courtesy of the artist.

It seems that the most important thing is that you have made a space for various new psychological states to play out, in this case literally psychological “states”! What strikes me is how seriously the delegates took role-playing. Because in a way it was also a state of play, a universal country of ridiculousness. And it is within this very psychological playground of absurdity that all of this was taken very seriously.

I believe that the mind loves cognitive dissonance. When you don’t know if it’s real or if it’s a joke, then you’re actually paying attention. And above all, the existence of the two possible interpretations, the coexistence of those two: Is this serious? Is this a joke? I’ve been talking with a neurologist, that I’ve had a long-standing conversation with, about how we get excited by cognitive dissonance. You are playing a role and you are aware that it’s a joke, and at the same time it’s serious. And that is exactly what provides you access. I have these opposing interpretations, that it all has to do with our own meta-theater. The mask frees you to perform roles that otherwise would be unbearable. Because if this were pretending to be serious it could be about worthiness or it could be patronizing, or it could be messianic, but you’re stating, you’re warning, that this is a joke and a game, so then people relax, and precisely because they are relaxed you can talk seriously. If you talk serious straight-talk to people you scare them off. You have to present it as a game for it to become serious; at least that was my framework for this project. In other scenarios there is a demand and a place for earnestness as well, and some aesthetic experiences demand this earnestness. For instance, in Sanatorium at documenta, I had different people coming in, but there always had to be a place for this ambiguity between play and earnestness; it was also a big role-play game. Suddenly I had some serious workshops that had to be conducted in full earnestness. I had a Protestant pastor at documenta who came to give a blessing workshop . . .

[Laughs]

Why do you laugh?

I laugh because it could have only been a Protestant pastor doing such a thing—the Protestants who once swore off aestheticism, and yet he’s doing it in a place that is highly aestheticized. On one hand it’s this very aesthetic experience of the blessing, one probably most associated with the aesthetics of the Catholic Church, but this priest would be reprimanded immediately if he was Catholic. He has traded one aesthetic venue for another . . . for an ethics and aesthetics of earnestness.

A blessing is something that has to be earnest. It consists of you saying something positive to someone and then complementing that with a physical gesture. Wishing someone good, it’s very powerful. Most importantly, it’s beautiful.

It’s interesting though that you use a blessing as being exemplary of earnestness in the face of role-play and an open-ended play in general. Presenting serious matters as a game was at the heart of the conversation you had with Antanas Mockus Šivickas at the Creative Time Summit. Can you introduce our readers to this project of Antanas’s and the conversation you two had around it?

Antanas Mockus is a mathematician, philosopher and used to be the mayor of Bogotá. I was interested in showing a very particular policy that he implemented that increased tax collection by 30% in Bogotá. He created something called “110% for Bogota,” where the citizens of Bogotá went to the tax service office to pay taxes and you could opt for paying 10% more and you could choose where that extra 10% would go. What was most exciting about the project was the idea of empowering people to take part in direct democracy. It was not something that you could do online—you had to go to an office to pay your taxes. He created a casino in these places.

At the beginning of the talk you remarked that he had “turned the entire city of Bogotá into a game.”

It was a very sophisticated and whacky game that worked. He has one of the wackiest minds I know. He created this pseudo-casino and people were using this kind of dreidel called a pirinola that you spin, which has six sides and it says things like put one, take one, take two, pass, etc. Every time you bet money you lose or you gain. Antanas is so sophisticated that he created a seven-side pirinola. So when you spin the pirinola, you will end with two faces up, so you have the freedom to choose whether to be selfish or altruistic, and that is how one decides how to spend this public money. The citizens became addicted to this democracy and were going back to the cashier to pay more taxes to get more points and bet more on which projects they wanted funded.

A fantastic phrase, “addicted to democracy.”

Yes! So tax collection was then able to be increased 30% because people were very excited to take part in this addictive and fun game to promote paying taxes. And if you paid 10% extra you were given these chips. For whatever you were paying you were given a stack of chips and then you could enter these tables where people were gambling for where the money should go, and you would bet on certain projects, which made the whole process very exciting. People would lose their money and then go pay more taxes to get more chips and get the projects they wanted funded. And these chips resembled and acted as the body of Christ, the hostia, and they said on them “Public Resources-Sacred Resources,” and the citizens were given a small piece of paper with which they had to classify where the resources would be put—social justice, roads, etc.—and he was trying to create a cultural change by saying that stealing public resources was a worse scene than stealing private money. He sees money given as a tax to be holy, and he was teaching people that the biggest proof of love for your country was to pay your taxes. That is how some of the pain of paying taxes could be relieved. You had to be extremely careful about how you handled your public resources. And so that’s why we ended the Creative Time talk by giving away these pieces that resembled the communion bread as if we were in mass. People made a line and we gave it to them in the mouth while saying “public resources, public resources” instead of “body of Christ.”

This blessing gesture you surprised the audience with was a brilliant mix of play and earnestness. And I believe Antanas beautifully placed it into language when he said at the end that he was convinced that humanity cannot change many of its problems without taking a look at religious traditions. I believe a lot in the importance of religious mythologies, aesthetics, and ethics in art. I am Catholic in this sense.

I am Catholic but I don’t know what I am now . . .

But, I bring this up in light of the certain dichotomy and dialectic that was at play, if you will, with the presentation you and Antanas made by giving the body of Christ as if at mass, because this gesture is at once the most serious, and indeed earnest gestures imaginable if you are a believer, but the way it was presented was very playful and childlike, and outside of the usual context it’s given at the Church. It seems to be a fundamentally artistic gesture.

Antanas would say so. One of his favorite quotes is, “When I don’t know what to do, I ask myself, what would an artist do?” And so now I ask myself, “What would Antanas do?” To me he’s a genuine genius.

You have said that your artwork has an intention to heal. Can you speak a little bit about this?

The idea is not creation for creation’s purpose; I believe that art has to have a purpose. At least for me. There is this story of Bashō, the Japanese poet, who is working with an apprentice, walking in a field where there are many dragonflies, and the apprentice says, “Master, I have a haiku,” and the master says, “Okay, tell me.” “A dragonfly takes out its wing and you have a pepper pod.” And the master says, “No, that’s not a good Haiku. You have to say, ‘take a piece of pepper, and add wings and it’s a dragonfly.’” So it has to be something that adds positively and that is a kind of healing process that reveals something beautiful and good, and I’m not afraid of having that ethos, that moral intention in itself. That’s why I insist on, you know, that the work is not completely open-ended, that the work has an intention to heal. It’s about healing.

Drone Dove, 2013, artist rendering. Courtesy of the artist.

In this sense it’s an Aristotelian ethics, something which aims toward the good and the positive rather than inverting things.

It’s a categorical imperative. And I acknowledge that this is strange within the art world, because in the art world there is a kind of parenthesis or exception where you don’t have to be ethical, you only have to be aesthetical. I don’t know why, but I believe that things have to make the world better. And I don’t believe that all art has to be like that. It’s only something that I ask for most of my own work.

When I create group activities I hope for collective creativity and spontaneity to produce a spectrum of different ideas. This is coming from Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed. He is possibly the most important philosopher from Latin America in the 20th century. He states an obvious thing: there are the rich guys and the poor guys, and the rich guys think the poor guys are inferior. You cannot expect change to come from above—you have to teach yourself if you want liberation. One must take responsibility for one’s own liberation process, and when you have a problem you have to socialize the problem. Then I have to turn to Augusto Boal because he takes Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed and he creates Theatre of the Oppressed, wherein what you do enunciate the problem with a one-act play, a short play, with a critical moment where the oppressed face all the oppression, and you don’t have a solution. Then you stop the play at that moment, and you invite the audience to contribute with solutions, but they cannot verbally say the solutions, they have to act them out. The people from the audience come on stage and decide which actor they want to replace and then you have different endings. You have a problem and you have the audience who become “spect-actors” through which you explore all the potential outcomes of the problem. You have a spectrum, a rainbow of solutions.

In the end it is about the difference between learning and teaching, learning and being taught. Augusto Boal says that the whole problem started with Aristotle because Aristotle was a hack for the government, you know? Aristotle, when he created the idea of tragedy, he was first of all saying, okay, drama is going to be a prescription where we’re going to show what those people should not do, because if they do that they will end up destroyed. So you should not sleep with your mother, etc. . . .

Yes, of course. This is the double-edged sword of the Aristotelian ethics of the good, “You must do this.”

Yes, Aristotle alienates the audience by creating the chorus. You don’t need to participate now that there’s a chorus that will sing for you, that will lament when there is disgrace, or will celebrate when there is victory. He alienates reactions from you. He basically separates the audience from the actors and he kills spontaneity and agency from the public. Augusto Boal and Jacob Levy Moreno, through psychodrama, group therapy, and the encounter movement, basically brought back theater to its primitive stage where the audience could participate and change the end of the play.

One can change the trajectory of the story because they have their own understanding and not someone else’s.

I believe that you have to create an idea that the audiences can experience and make as their own. If an idea is truly valuable everyone will understand it. The idea that an artist should not create small curtains—basically, I don’t want bullshit.

I see a kind of curatorial dictation in art today that reminds me of this flaw of Aristotle’s—all too often the way an exhibit is organized and written about demands an art spectator to experience it with a strict, often oppressive pedagogy, where they tell you how to look at a piece of art. That seems like bullshit.

Well, I like obscurity and I like art—I enjoy some art about art. But I don’t expect other artists to follow the same rules that I make for myself. I don’t think that it’s bad that there’s self-referential art. But I do believe that art should speak to most people, even though when I do this I put myself in a risky position because I know that in reaching out, your audience may have curators in it.

But what I appreciate in much of your work and your thought process is what I see as creations of open spaces that let the viewer see for themselves, spaces that one can navigate on their own and decide between what is good and what is not, because the most basic and yet most profound thing one can understand is their own lived experience.

I have a kind of a very personal dogma that my work has to be understood by everyone.

Has to be or could be?

Has to be. Yeah.