I stop into a morning bar to kill time before meeting with Richard Hell at his East Village apartment. I have a couple whiskeys trying to unwind after having spent the previous day rereading his autobiography, I Dreamed I Was a Very Clean Tramp, in preparation to interview him. It’s pouring rain, and by 11:45 a.m. I walk a few blocks to meet him at his place.

He’s on the phone and I wait for him in the living room. I snap a few secret photos of his black cat and his apartment that I can best term kooky. It’s a classic Lower East Side flat, with slanting walls, high ceilings, a bathtub in the kitchen, and a palpable feeling of home. His walls are adorned with shelves of books and artwork, and I try and wrap my head around living in the same place since 1975. But this is New York: when you get something nice you hold on to it.

Throughout his music career he pioneered a sound that I describe as incendiary, sharp, and fucking sexy all at once, and not just because a high school girlfriend and I used to jerk each other off to “I’m Your Man” or “Love Comes in Spurts.” His image was innovative and vociferous, his lyrics forward and imaginative. The music he produced has had an immeasurable influence on rock and roll’s legacy, offering a no-bullshit sensibility that rivaled the pompous arena rock of that era and continues to rouse musicians today.

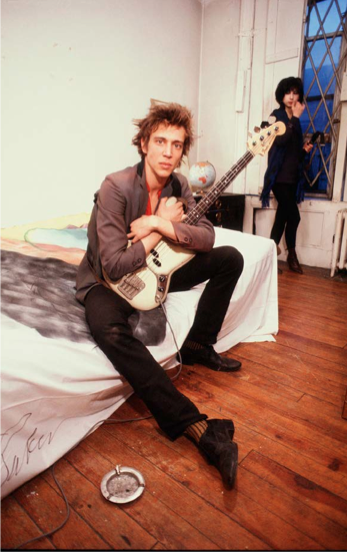

Richard Hell moved to New York City at the age of 17 in 1966 to become a poet with ex-band mate Tom Verlaine before being sidetracked by their musical collaborations, Television and Neon Boys. After Hell left Television he was the vocalist, bassist, and lyricist to The Heartbreakers with Johnny Thunders and Jerry Nolan.

With the exception of a brief musical project called Dim Stars in the early ‘90s, Hell left music for good in 1984 after the release of his second and final studio album, Destiny Street, as Richard Hell and the Voidoids. The Voidoids’s 1977 debut album, Blank Generation, is widely considered a punk classic, and its title track the anthem of that decade.

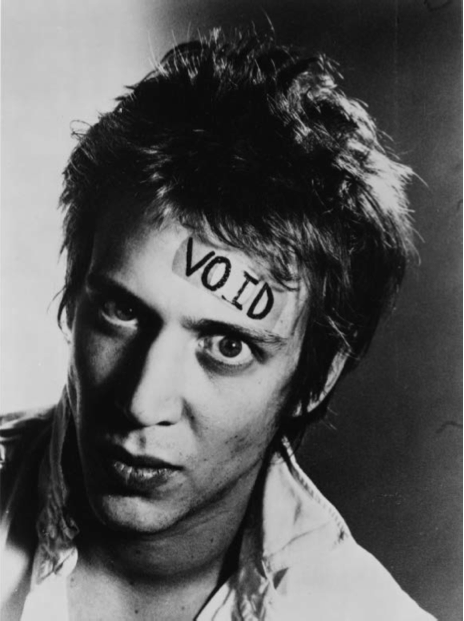

Richard Hell, 1977. Photograph by Kate Simon.

Since leaving the stage Richard Hell has devoted himself almost entirely to writing, including two novels, Go Now (1996) and Godlike (2005), and a collection of short writings and drawings entitled Hot and Cold (2001). Most recently published was his autobiography, two years ago.

I Dreamed I Was a Very Clean Tramp is an unforgivingly honest account of his life from boyhood in Lexington, Kentucky up through when he quit music in the 1980s. From having been a pivotal engineer of punk and the downtown rock and roll scene to his very descriptive and, well, provocative depictions of his sexual encounters with . . . a lot of women. Hell is unapologetically a man who knows how to use his love muscle, and that essence of shamelessness, authenticity, and candor extends into his music and writings.

SPOILER ALERT: He doesn’t die in the end.

I love the story behind the title, so I ask him to remind you readers where he got it.

I’m a little bit ambivalent about that title. Sometimes it really seems stupid to me. But I usually like it a lot, and in context I really like it. The context you’re talking about, which is where I got it from, how it arose and arrived, is the story of when I was a kid and I just loved to run away from home. It was my favorite thing to do. It was always the most exciting possibility, and not because I had some horrible childhood or terrible home life, not at all, it was very comfortable. But I was just thrilled by the idea of going some place unknown and being someone that wasn’t known to anyone and having adventures. Anyway, it’s common among kids and I tell a couple of stories about runaway experiences in the book. I did it almost annually until I finally succeeded when I was 17.

My father died when I was seven and one of these stories of running away happened just a month or so before he died. He played a big role in this anecdote about running away. And as it turned out, this specific memory I had of running away, which was really significant to me, wasn’t remembered at all by either my mother or my sister. As I said, my father had died just months after it occurred, so there was no way to confirm exactly what happened. For almost everything in the book I have some way of confirming, somebody else I could consult. But I had no way of checking this story. My wife teased me about it, that I was making it all up, and the way I remembered it was probably wrong. But my mother keeps everything and I happened to come across this story I wrote for school two months after this runaway happened. It told the whole sequence of events. I was able to confirm that the way I remembered it actually was correct. And it was really a triumph. The story was called “Runaway Boy.” I had turned eight by the time I wrote it, and it recounts what happened that night and how the runaway feels and having to return home and go to sleep; the last sentence of the eight-year-old’s story of how he had run away a couple months before was how he returned home, went to bed, “and I dreamed I was a very clean tramp.” So that’s where the title comes from.

At the end of your autobiography, you write that one of the reasons why you wrote the book was that you wanted a say in your own reputation.

That’s interesting, nobody has ever quite put it that way. Well, but that’s not in the context of why I’m writing the book, that’s in the context of the book being really frank. Even when it reflects badly on me.

You write, “My life only comes into being by having been written here.” Basically, if a tree falls in a forest and nobody is around to hear it, does it make a sound?

Yeah, but it’s not even that, because there’s a lot on record about things I’ve been involved with because it’s been written about and stuff. You could draw conclusions about certain stuff I’ve been involved in because there’s a record, whether it’s books I’ve written or records I’ve made or stories that have been told about that era in New York or whatever, but the point of that sentence in the book was that a lot of my motivation in writing the book was to try to grasp what the fuck happened. What it all added up to. I wanted to embody it in this object, which is a book, in order for me to try to have some understanding of it.

It’s all so amorphous. You never really have a reality in a certain way. You’re always just part of a flux. And you might have a memory for a second, you might have a plan, or you’re just reacting to some kind of stimulation you’re getting, but it’s all just sort of chaos. It’s funny, I also realized that in the writing of the book—there were a few people, a few reviewers, who made comments in a kind of skeptical way about how here and there I quoted people from decades and decades ago, or described something in great detail, and they wondered whether I actually could put in quotes faithfully, reliably, two sentences that somebody said to me in 1969—but the fact is, I only ever did that, and the only way that I was capable of doing that was because I kept journals at that time. Those were all things that I actually noted as they happened. Which is another example of the thing I’m talking about, because I wrote it down and I was able to keep it, and that’s also true for me, having a life period. It really only comes into being by having been evoked in concrete detail, and just material form. Otherwise, it didn’t even happen!

That’s also the nature of being an artist for so long and living and working as an artist. You’re constantly, even subconsciously, planting seeds for future projects. So things are always in the archives. It might be in the form of journals or in drawings, sketches, and other materials. Even if you’re not using it now, you might pick it up again one or ten years later; it’s always in the bank, so to speak. So in that sense you have these journals you can go through.

Yeah, I really did feel like if I wanted to have had a life, it needed to be written. I mean, for me, in a certain way books are more real than people anyway!

They have a better smell.

You never actually know what’s going on with somebody else. But in a book you can really study it and it doesn’t change. You change and so you might be able to derive something new from the book because of some way in which you developed. And so, yeah, I wanted to have a life, so I wrote a book!

In your earlier bands, from the Neon Boys to Television to The Heartbreakers to The Voidoids, how big a part did the way you dressed and presented yourself play in your life and music? You write, “[We] were the positive standards of being, rather than examples of failure, depravity, criminality, and ugliness. . . . The traits and signs of what came to be called punk were the ways that we’d systematically invented or discovered as means for displaying on the outside what was inside us.”

I wanted the clothes to be consistent with how I wanted to be perceived. I was aware that people chose what they wore and that I wanted to dress in a way that created the effects that I wanted to create. But then once I started a rock and roll band, it all sort of blossomed because I became aware right away, and it really turned me on. It really excited me and it was really fun—this realization that with a band there’re all these means of communication besides the songs. And I never really consciously thought of that before. I knew it, but it wasn’t conscious, that in a way a band is like a whole subculture—I mean, in itself, when it’s done right, when it really exploits all the possibilities. It’s a subculture that’s expressed in the graphics of their posters and album covers, in their hairdos, in their clothes, in the things they say in their interviews, in the way they behave on stage. All of those things are means for communicating what you want to be saying, how you want to affect the world. So the whole issue of how you dress took on this new force once I started thinking that way consciously. It’s not just me on whatever kind of relatively mundane level wondering if I wear madras or not. Without any censorship or convention or hesitation or inhibition, I want the clothes to say the same—to sort of represent on the outside the way I feel inside, you know? And all of the sort of things we were trying to do in the band that were different from what was popular and acceptable and conventional at that time could have an equivalent in the way we appeared. So I sort of methodically thought through what I could do that would represent what I felt like inside. That was about the raggedy, patchy hair and the torn-up clothes with writing on them. I just thought through what means I could come up with to have the clothes be consistent with everything I wanted to be throwing at the world.

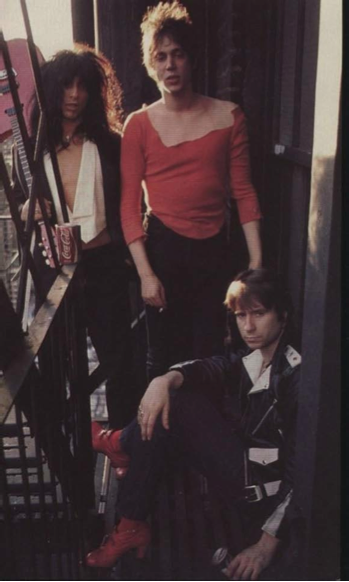

The Heartbreakers, 1975. Photograph by Bob Gruen.

Do you feel like there is still a conscious decision as to how you present yourself?

Well, that’s definitely built into me but I don’t give it anything like that kind of attention anymore. In a way it was almost like an art project.

So many people that you worked with in music or that you were friends with have died, many from overdose. Did you ever imagine that you’d make it this far? Do you ever look back and say, wow, I really dodged that bullet?

Well, I feel lucky in certain ways. I’m glad I’ve lived this long, but I’m kind of getting a little bit tired of it! You know, it’s always seemed to me that I had a little advantage over people in music who would find themselves kind of at a dead end because they had no other options. And there’s a lot about rock and roll that is dangerous. It’s all kind of about pure self-indulgence and never growing up, and that covers it pretty much. Never growing up and self-indulgence. You can’t stay a teenager for your whole life, and if you try to you’re going to start having psychological problems. And the whole self-indulgence thing, which includes drugs, is also really risky. I kind of had other options and interests, but you know, at the same time, I OD’d a few times—I mean, woke up in the hospital without any knowledge of what happened and immediately said, “I want some more of that! That was really good!” So a lot of it is just pure chance. I never had such a death wish that I actually assumed that I was going to die before I was 30 or 40 or whatever. I wonder if you did some kind of statistical study that you’d find the life expectancy is a lot less for the rock and roll demographic. I wonder. I’m not actually sure. A lot of people have lived, too.

What are your thoughts on contemporary rock and roll? Obviously it has changed a lot, but is there anything that stands out now?

You know, I’m not hooked into it. Back in those days rock and roll was everything. It was life and death. My impression now is that it’s so diffused because of the advent of digital recording and the web where anybody can disseminate anything and everything is basically free. It’s just become kind of Balkanized, all these hundreds and thousands of little pockets. I really just don’t know enough. When I try to keep up, it’s too overwhelming. Every once in awhile somebody recommends something you know, and I’ll listen to something, and sometimes I find something that I like, but I have no idea really what all is out there.

Yeah. I don’t either! So you’ve done acting before. It seems like you haven’t acted much since the ‘90s.

Yeah, I never was serious about acting. I was basically living hand to mouth and sometimes every once in a while somebody would ask me to do something in a movie and if they would pay me I would do it. It was never something I pursued and I don’t really feel cut out for it, frankly.

Is there a film that you acted in that you liked more than the others?

That was good? Well, by far the best and my most successful attempt to have a role in a movie was in Smithereens, Susan Seidelman’s first movie. But I didn’t do very many, only four or five.

So you didn’t enjoy Ulli Lommel’s Blank Generation?

That movie just repels me and makes me shudder and vomit. But the fun thing about that was when they recently re-released it on DVD and they asked me to contribute in bonus interviews at the end of the film and I had them agree in advance I could say what I want. I got to spend 45 minutes completely trashing the movie!

You’ve been in New York for almost 50 years. In what ways do you feel like it’s changed, and what keeps you here?

There’s really no vestige of the New York of my youth anymore. New York is a theme park for the smug and arrogant wealthy. But it’s kind of been convenient that I aged as that sort of thing developed because I don’t play rock and roll anymore, I don’t do drugs anymore—all I need from New York are movies and museums and art galleries, the things that still thrive here. I cannot stand going out on weekends when the streets are mobbed with rich people barhopping, Wall Street types and college kids and shit. But I still have my apartment, I’m very lucky. So yeah, I feel for anybody who’s like me at that time, now.

That whole culture—it was crime ridden and dirty and there was a lot that was ugly about it in certain ways, but also you had nothing to lose and apartments were cheap; jobs were plentiful. The fact that it was like the Wild West also brought a certain freedom to it.

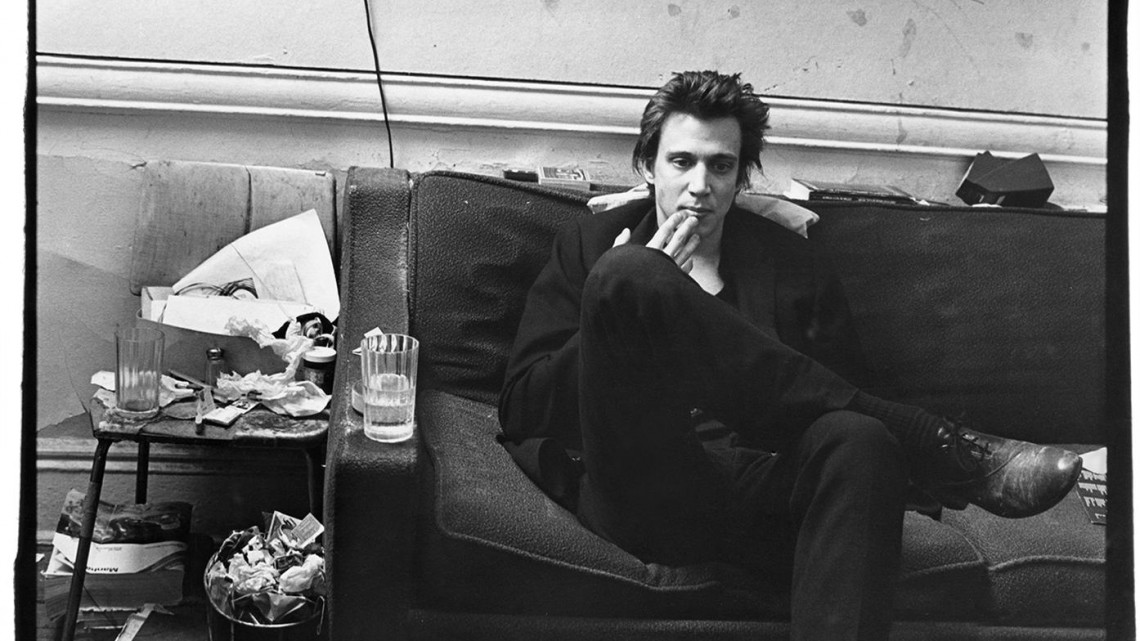

Richard Hell in his New York City apartment, 2014. Photograph by Dean Dempsey.

Richard Hell in his New York City apartment, 1982. Photograph by Roberta Bayley.

New York leads the country in both homelessness and luxury rentals. All around my neighborhood these generic posh condominium are popping up, and under their construction scaffolds are almost always five to ten homeless people living in boxes. The rate of poverty and the influx of the wealthy moving in is nuts. It’s becoming a third-world country. You’re very poor or you’re very rich. But anyway, that’s my rant. So you were working on a movie in 2007—where is that?

This kid came to me at a reading of mine with a DVD where he shot a chapter of my first novel, and he had done a really good job with it. He put himself at my disposal. He was a film student and just near graduation and he could handle all aspects of making a film. He had a camera and editing software and he just asked me if it was anything I’d like to do. I couldn’t resist, so I started toying with this plan for a movie and shot this little experimental piece to see what it would look like. I had some experience messing around with writing film scripts, trying to get something done in the past, and I realized the single-mindedness and persistence and sacrifice it takes to get a first feature made. I mean, you have to do nothing else for like five years. It takes all of your energy and all of your focus, and it’s a horrible struggle. And all this money.

So I basically gave up on this years ago, but then this kid came up and I thought why not give it a shot because things had become easier due to digital film making, so I did play around with this thing and shot a few minutes and put it up on YouTube. It exposed how thin my commitment to doing it was because I knew how backbreaking it is. We were shooting in available light, and he told me that it was going to be plenty for the equipment he was using, but it turned out really dark and it wasn’t something that would have been usable. That was enough to say, okay, never mind, I’m moving on!

Is it on the back burner or are you just going to move on from it?

It’s completely set aside.

Do you ever consider acting again?

No. Every once in awhile I get some kind of little something about doing something, but I’ve had no trouble resisting. I’m just not cut out for it. I don’t like the experience. I liked doing it for a clip I put up on YouTube in 2007.

Which one?

It’s called Melinda’s Neck. I was in my element so it was comfortable. I wasn’t having to contort myself into somebody’s idea of a role. I really can’t do that, I don’t have the acting chops. I’m too self-conscious. I can only be confident when I’m actually relating with somebody, and that’s the way we made that movie. We were kind of more or less improvising, and we were just relating to each other. We weren’t trying to fit into roles.

What was the last movie you watched that you enjoyed?

The new Jean-Luc Godard 3D movie, Goodbye To Language. He’s over 80 years old now and has been really prolific. This is my favorite period of his, the last ten years or so. I’ve always loved him, he’s just amazingly fertile; he keeps going new places and he’s brilliant. He uses different types of cameras, like the cheapest possible $200 digital video camera you can buy, up to 35 mm; I’m not sure what he used on this particular film, but different kinds of technologies. If I’m not mistaken, he actually even created his 3D camera just by taping together two cameras himself. But it’s really effective. It’s really good, and it’s an amazing movie. I can definitely recommend that.

What is this performance series you’re doing, Night Out with Richard Hell?

Well, this agency approached me back in the summer asking me if I would be interested in curating a series of performances at this uptown venue called Symphony Space. The concept was that I would interview the performer and they would do their act. I didn’t even understand what they were proposing at first. I thought they were just asking me to do one in a series, but it turned out they wanted me to do five of them across the winter. They were looking to get young musicians. They thought I could bring in who I thought was interesting to do stuff in New York now. But I don’t really keep up, I didn’t really have five young musicians, and I didn’t really relish the prospect of having to go out and cruise nightclubs. So I asked if they would let me present performers in other media, and they agreed. It was really fun and I didn’t know what to expect. I’d never done anything like it. Four or five people came to mind that worked in completely different areas who were relatively unknown. There were two bands, a poet, a filmmaker, and then an artist who made his original reputation on YouTube. I’m interested in painting and art, and I have a lot of friends who are artists and I love going to galleries. It was kind of frustrating that I wasn’t going to be able to include a visual artist in the series. What was he going to do for his performance? Stand up there and paint something?

It’s a little bit stressful, but it’s kind of a challenge and an adventure and I’m really getting off on it. I am pleased with the lineup that we’ve got together. The first one is a 22-year-old Cow Punk. Did you ever hear that? I hadn’t. She’s like a country musician, but she comes from a background where she’s sort of liberated by what punk music was doing. It’s very aggressive and frank, and she’s a wild child. Her name is Lydia Loveless; she was the first one. The second one is a poet named Ariana Reines, who’s this funny picture of sort of bag lady and extremely sophisticated intellectual. She’s a genius poet, the real thing—it’s like you’re talking to Gérard de Nerval or François Villon or something. She lives it. And then in December was Kelly Reichardt, a filmmaker. I interviewed her and then screened her movie. In February will be Donald Cumming who has this band called The Virgins, but it’s no longer, and his new record is a solo record, but he also has this real interesting history being a street kid junkie who fell in with Ryan McGinley and was opened up to things by that whole experience, and ended up having a career because he made this little home-recorded set of five songs he had written that he put on CDs for just a few friends. Then within a few months there was a bidding frenzy for them and he found his way into the music business. He’s really a talented and interesting guy.

Then the final evening is this artist Jayson Musson, who shows with Salon 94. He’s a commenter on the state of the art world. The videos he made for YouTube were wildly popular and funny; really comic and insightful about art making. He did that under the assumed name of Hennessy Youngman. He made this series of videos where he adopted this kind of rock star persona and dissed the art world. They’re really hilarious. But this guy is the one person who I hadn’t known about before I took on the assignment of doing this series, and he was perfect because he had done this multimedia stuff.

So yeah, it’s funny to move from artist to artist like that and have this whole intense relationship going on in sequence with these very different people. It’s edifying and it’s stimulating. They’re all different personalities and all work in different areas, and it requires me to do a lot of research because I have to get familiar with what they have done. It feeds me, I like it. I mean, it is hard work, and I should be writing a book instead.

What’s next?

Well, the main thing is a new book. I’m still not sure if I have the stamina, but what I’m trying my hand at is a cold-ass noir novel.