To encounter ambitious contemporary art, you must also encounter the world of the international curator, the most prominent member of the global art world. He’s there at the gala preview, she’s up at the lectern laying out her concept for the biennial, they’re there when you flip through the exhibition catalog. She’s interviewing, or being interviewed; he’s profiled in Artforum or a fashion magazine. What are they saying? It begins, and perhaps ends, with a kind of utterance that reliably ushers you into their world: (a) “The very idea of a ‘work of art’ is a particular invention of our culture” (Jean-Hubert Martin); (b) “It’s clear that the museum as an institution in the West represents a love of the image, of the picture, on which the objectivity of gaze [sic] confers cultural value to the image” (Okwui Enwezor); (c) “We are living in the society of the spectacle. In spite of its alienating effects on our life and social relationships, it is one of the very fundamental conditions of our existence” (Hou Hanru).1 What are such sentences saying? And perhaps more importantly, what are such sentences doing?

Such sentences are undeniably a part of the most authoritative framework for understanding contemporary art. For the past two decades, the most typical characterization of recent visual art and its cultural settings is that, whether the art of our era is best thought of as postmodern, post-conceptual, or post-colonial, we live in the Era of the Curator. In one influential statement, Michael Brenson remarked after listening to three days of curators’ talks at the Bellagio Center in Italy in 1997, “It was clear to me that the era of the curator has begun.”2 The curator in this sense is not just any curator, but is the type of internationally prominent curator of the world’s biennials and triennials. Of the authors of the sentences quoted above, Martin was the curator of the exhibition that seemed to open this age, Magiciens de la Terre (Magicians of the Earth) of 1989, and Hou and particularly Enwezor are among the most prominent recent exemplars of the type. A recent Wall Street Journal profile of Enwezor suggests that we should ignore the verbiage that accompanies his exhibitions and just look at the show. This suggestion may well simply ratify existing practices; anecdotal evidence suggests that few visitors to a biennial concern themselves with the exhibition statements, and a notable feature of the reception of such language is the difficulty of finding any extended consideration of it. Might the most authoritative framework for contemporary art carry little authority?

Certainly the sentences themselves neither invite nor reward critical scrutiny. Consider just the gross features: (a’) Martin’s scare quotes around “work of art” intimate that there is something problematic about this conception, but what? Does he mean to suggest that the concept of an artwork has no legitimate trans-historical or cross-cultural usages? What does “particular” mean in this context? On one charitable reading, Martin’s sentence might be taken as the beginning of an investigation into the ways in which in which a particular conception of an artwork rises around 1800 and attains dominance in the arts; the classic essay The Modern System of the Arts by Paul Oskar Kristeller lays out the emergence around that time of the conception of “fine” art, and more recently scholars such as Lydia Goehr, M. H. Abrams, and Larry Shiner have explored the concomitant shifts in conception in particular artistic media, respectively music, poetry, and the visual arts. No such investigation follows.3 (b’) Contrary to the opening “It’s clear,” in fact nothing is clear. Enwezor then puts “of the picture” as a qualifying apposition of “of the image,” but of course pictures are not simply images, and art museums “in the West” typically include a few sculptures along with their pictures. And Heaven knows what Enwezor means by “the objectivity of the gaze”; is this a subjective or an objective genitive construction? That is, is the gaze supposed to be something exhibiting a kind of objectivity, or is it that the activity of the gaze creates objectivity? And if the grammatical construction were clarified, would it then mean anything determinate? What is “cultural value,” and is it something that can simply be conferred by “the objectivity of the gaze”? (c’) What does “its” refer to in Hou’s second sentence—society? The spectacle? Are we supposed to think that society, conceived in abstraction from the spectacle, is something un-alienated? Hou fails to provide any explication of how he interprets or means to apply Guy Debord’s term and thought. And it (whatever “it” is) is “one of the very fundamental conditions of our existence.” What are some equally fundamental other conditions? What’s the difference between a fundamental condition and a very fundamental condition?

Although never explaining what the particular idea of a “work of art” was, in the catalog for Magiciens, Martin does at least offer what he thinks the replacement conception adequate to contemporary art should be.4 What all the works (Martin calls them objets [objects]) in the exhibition share is an “aura” and a purpose: they are made to “act in the mental realm and on the ideas of which they themselves are the result.” Further, Martin claims that they all communicate some meaning by virtue of the fact that they bear “metaphysical values.” Supposedly we call the way in which art exercises its “living and inexplicable influence” a kind of “magic,” and because many of the world’s cultures “are not familiar with the concept of art,” the people who make these works are not rightly called “artists,” but rather “magicians.” Well, that’s something, but as with Enwezor’s talk fifteen years later of cultural values, Martin’s invocation of metaphysical values never explicates how objects gain the relevant sorts of values, nor what distinguishes this kind of magic from the familiar kind of seemingly sawing people in half.

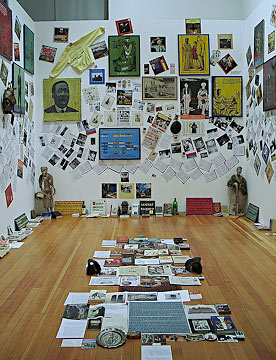

Installation view, “Cities on the Move,” Vienna Secession, 1997. Curated by Hou Hanru and Hans Ulrich Obrist.

One common explanation of the prevalence and prestige associated with such talk is that it is not meant to be understood; it functions, with great reliability, to police the social distinction between art world insiders and outsiders. Insiders are those who produce such talk, or who nod or grunt affirmatively every few minutes as it unfolds. Outsiders are those who look bewildered or bored or outraged when they hear the talk. Of course such explanations have also been offered in earlier episodes of peculiar art talk, such as the theory-speak of the 1980s and 1990s, but such an explanation is silent as to why the curator and her speech have become such a prominent aspect of contemporary art, and what effects such speech have.

One possible route to a further explanation might be to consider the very need for a person fulfilling the role of the international curator. The philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre has urged the point that to understand a moral philosophy we must set it within the social context that is its home and which provides it with its aim. In some cases this task will involve constructing a “character,” an ideal type of a social role that embodies the representative aspirations and moral aims of a culture.5 MacIntyre offers sketches of three prominent characters of late modernity: the Rich Aesthete, the Manager, and the Therapist. The Rich Aesthete is someone who pursues “the interesting” as a way of warding off the worst of life’s states, boredom. What is “interesting” is generating and fulfilling ever-new wishes and desires. For the aesthete, other human beings are occasions for entertainment. The Manager is part of an organization’s bureaucracy, wherein the aims of organization are determined by its attempts to maintain and expand its position within a competitive struggle for resources and prestige. The Manager aims above all at “effectiveness”—the most efficient use of “resources” (human and otherwise) towards realizing the relevant institutional goals. Similarly, the Therapist treats the aim (“adjustment” or “mental health”) as given, and uses whatever techniques required to turn “maladjusted individuals into well-adjusted ones.” A negatively definitive mark of these characters is their inability qua characters to engage in moral debate about their aims; in each case the aim is set prior to any individual’s making herself into that character. The social setting that is common to these characters is positively marked by “emotivism,” wherein judgments of moral or aesthetic evaluation are grasped as nothing more or other than personal preferences, and where the distinction between manipulative and non-manipulative human relations is lost. Is the Curator a character in this sense?

An often noted feature of the Curator is her need to communicate with very different audiences and clients: the national and international interests who finance the exhibition; the artists included, who in many cases have been set specific tasks or commissions by the curator; the various local audiences, whether or not savvy to the latest trends in art; the jet-setting art world of the scene-makers, the mile-high bourgeoisie, critics, fellow curators, and art pilgrims. Something of this need to, if not communicate, at least resonate with these diverse audiences may account for the un-eliminable indeterminacy of the curator’s talk. Terms are used (“society of the spectacle”; “multitude”; “center and periphery”; etc.) that have their home in theoretical constructions of some complexity. In using those words the Curator signals to those in the know, but the use must also allow each of the other audiences to project something into the language, and to think itself finding something of significance there. The un-eliminable vagueness of the Curator’s speech may not in every case be maligned. After all, obscurity and indeterminacy are not always negative features of a linguistic style; it is part of the greatness of Rilke, Vallejo, Celan and a vast array of other modern poets that their work cultivates such qualities.

Like MacIntyre’s characters, the Curator, and the art world generally, are surely at home in the emotivism and moral anarchy of the present. One badge of seriousness in this world is to denounce the purist version of normative formalism advocated by the critic Clement Greenberg after World War II. Such denunciations slide easily into a general rejection of allegedly ‘objective’ criteria of taste and quality as crypto-authoritarian attempts to constrict the possibilities of contemporary art. However, the international Curator does display a kind of freedom denied at least to the Manager and the Therapist, in that she is bound only the very general aim of making the most interesting exhibition she can. Part of the shaping of the aim of any particular exhibition involves a diagnosis of the present, and this diagnosis is given in part in what are on the face of it concepts at home in ethical reflection, such as justice, responsibility, fairness, or obligation. By contrast, again, the Manager and the Therapist must accept the more determinate ends of efficiency and adjustment in taking on those very roles.

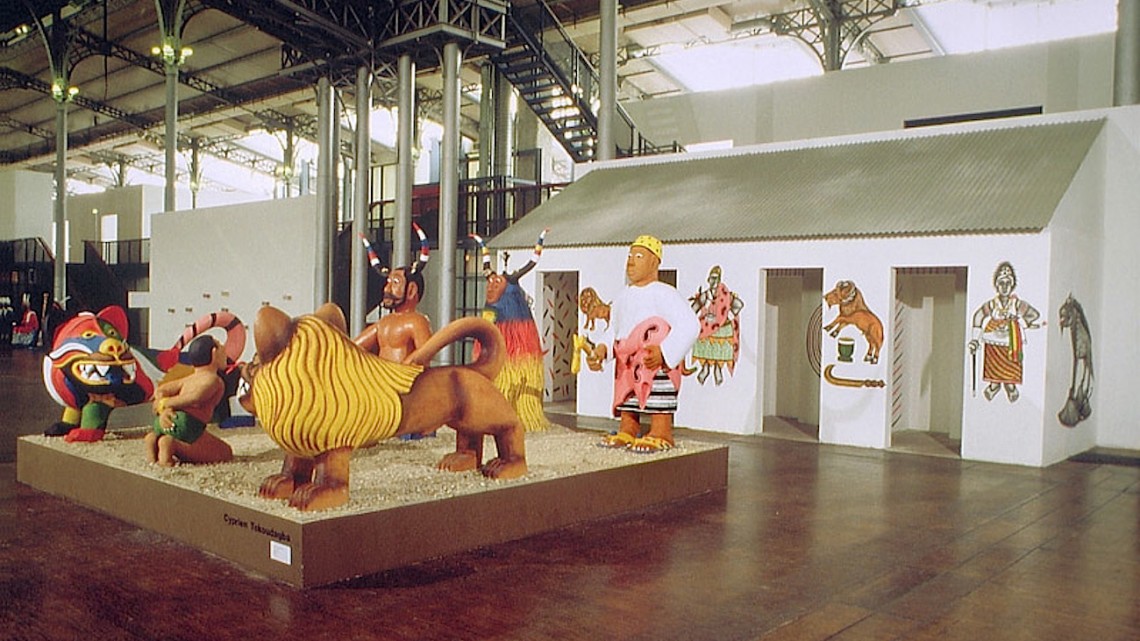

Installation view, “The Short Century: Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa 1945-1994” at Walter Gropius Bau, Berlin, 2001. Curated by Okwui Enwezor.

One part of the problem of the Curator’s speech remains superficial, albeit pervasive: its clumsy and over-heated quality. A good rule of thumb is that the more ambitious the Curator, the worse the style. The problem is familiar to every college teacher of composition: when the author has little to say, but feels the pressure of making a Big Statement, the reader is confronted with abstract nouns doing and having done to them all sorts of thinly characterized actions, with a high percentage of passive constructions, dangling clauses, and modifiers that modify nothing. Perhaps the fabled awfulness of Enwezor’s prose is in part due to his pitched ambitions. Accordingly, the common objections to the Curator’s talk—its hollowness, pseudo-intellectualism, vapidity—strike me as almost invariably accurate. But perhaps these objections are not definitive if qualified by the sense of the strenuousness of the Curator’s ambitions.

The problem is deeper. The most serious objection to such talk, to my mind, is the characteristic way in which it blocks self-reflection or even the beginnings of self-clarification. Michael Baxandall once noted that even the most puzzling, obscure, or even tautological statement in art talk may come to have a meaning, and even offer illumination, in the presence of a work.6 Adapting Baxandall’s example, imagine someone saying “the design is firm because the design is firm” in the presence of a simple gouache. If we can make anything of this, two conditions at least must be in place: First, we must import something of a background sense of what graphics as an art consists in. Part of this will necessarily involve some conception of the artistic process, wherein an artist engages in an activity governed by some conception of what she wishes to create, and monitors and sustains a feedback process involving an enormously complex set of actions and reactions. The process may go awry in countless ways, but if it succeeds, as it must do with some regularity if it sustains a living practice of art, something results which exhibits some kind of inner organization. Second, the sentence must in some sense be juxtaposed with the work. As we consider the sentence and gaze at the work, something of the sentence is clarified: the first part (“the design is firm”) refers to the inner organization of the work; the second part (“because the design is firm”) refers to the artistic process. What gives rise to further thought is the “because”: in what ways does causality operate here?

So one way of seeing what misfires so badly in the Curator’s talk is to note that it typically occurs in the absence of the works. The Curator imagines that she addresses the sense of historical necessity and possibility, but the talk latches onto nothing. But surely the Curator would respond by noting that in her exhibition previews and talks she does show and discuss various works. The problem, though, is that the Curator lacks a viable conception of the artistic process. One sign of this in the quotations from both Martin and Enwezor is the indication that in some way values are embodied by works of art, but neither author offers the slightest indication of how this occurs. It is part of the force of Baxandall’s example to show how damaging the lack of some sense of the ways in which the work process of the artist charges materials with meaning. And just how damaging is that?

To be continued . . .

1) The quotations are taken semi-randomly from the following: Jean-Hubert Martin’s proposal for the Magiciens exhibition, in Making Art Global (Part 2), 2013; Okwui Enwezor interviewed by Karen Raney in Art in Question, edited by Raney, 2003; Hou Hanru, catalog essay for the 10th Lyon Biennial, in le spectacle du quotidien/the spectacle of the everyday, 2009, p. 25

2) Michael Brenson, Acts of Engagement, 2004, p. 117

3) Paul Oskar Kristeller, “The Modern System of the Arts”, 1951-2, now in Renaissance Thought and the Arts, 1980, pp. 163-227; Lydia Goehr, The Imaginary Museum of Musical Works (1992, revised 2007); M. H. Abrams, Doing Things with Texts, 1989, pp. 135-187; Larry Shiner, The Invention of Art, 2001

4) Jean-Hubert Martin, in Martin and Mark Francis, Magiciens de la Terre, 1989, p. 9

5) Alasdair MacIntyre, After Virtue, 1981, pp. 26-28

6) Michael Baxandall, Patterns of Intention, 1985, p. 12