Hammer Projects: Mary Reid Kelley

May 23 – September 27

Hammer Museum

10899 Wilshire Blvd. Los Angeles, CA 90024

—

“What god is this that drives thee without sail

Before the wild winds of a wandering will

Thro’ salt sea-storms of soul’s distemperature…?”

-Algernon Charles Swinburne, Pasiphae

The self has never been stable. Unmoored from all certainty, tossed about in a sea of shifting passions, it is privy to “wandering will[s]” and fleeting fancies. So are the characters in Mary Reid Kelley’s trio of films currently on view at the Hammer Museum: Priapus Agonistes (2013), Swinburne’s Pasiphae (2014), and The Thong of Dionysus (2015). Figures from the Greek myth of Theseus and the Minotaur leap to life, their fears and frenzies less archaic than contemporary. Using an eclectic stew of references in language, costume, and set decoration, Reid Kelley transposes ancient attitudes to our present moment, revealing enduring facets of human subjectivity.

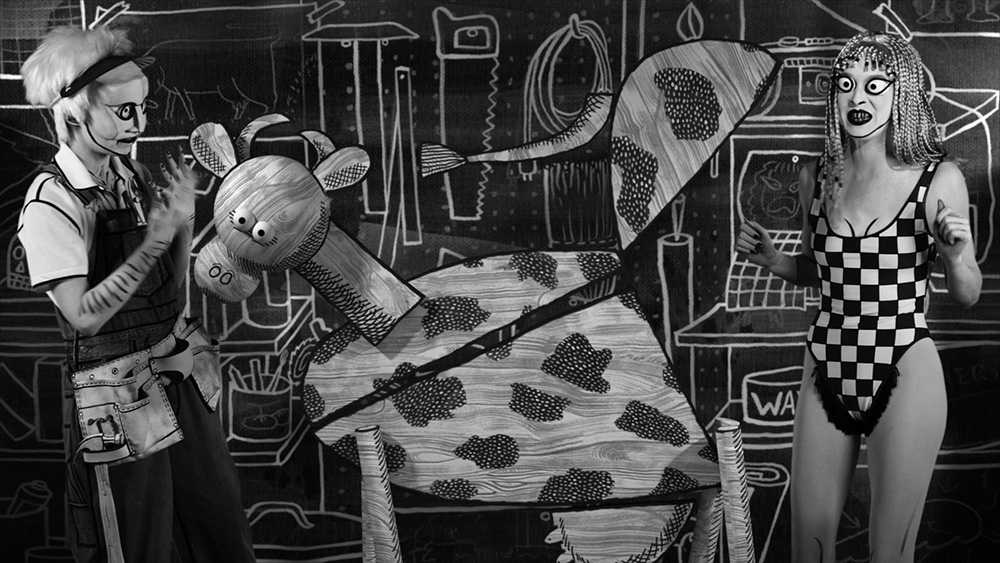

Mary Reid Kelley with Patrick Kelley, still from Priapus Agonistes, 2013. Single-channel HD video, black and white, sound. 15:09 min. Courtesy of the artists; Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects; Fredericks & Freiser Gallery, New York; and Pilar Corrias, London.

In all three films, a highly stylized black-and-white aesthetic transforms Minoan frescoes into living cartoons with the look of punk zine illustrations. Those familiar with Reid Kelley’s films will recognize her limited palette, painted masks, visual and linguistic puns, and comical allusions to classical mythology from past works like You Make Me Iliad (2010) and The Syphilis of Sisyphus (2011). For her project at the Hammer, Kelley painted and sculpted each prop and set piece by hand, their bold contours creating a backdrop of brilliant contrast, like the tales on Greek amphorae. The objects were arranged in front of a green screen that artist Patrick Kelley used to create composite images of various characters, all played by Reid Kelley herself. This high-contrast world is the setting for mercurial passions, their shifting gradients amplified by the physical absence of color.

The films tell the story of the Minotaur, Ariadne, and Pasiphae from three different perspectives. In the original Greek myth, when King Minos fails to sacrifice a beautiful bull to Poseidon, the sea god curses Queen Pasiphae to couple with the animal. The union produces the Minotaur, half-man, half-bull, who is locked in a labyrinth and fed an annual tribute of fifty Athenian men and women. Athens’ greatest warrior, Theseus, travels to Minos to battle the beast and free his people from innocent slaughter. With help from Ariadne, the neglected daughter of Minos, Theseus kills the Minotaur and sails off for his home polis.

Mary Reid Kelley with Patrick Kelley, still from Priapus Agonistes, 2013. Single-channel HD video, black and white, sound. 15:09 min. Courtesy of the artists; Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects; Fredericks & Freiser Gallery, New York; and Pilar Corrias, London.

In a comically contemporary update, Reid Kelley’s trilogy opens on an indoor volleyball court, where rival church teams face off to determine which loser will be sacrificed to the Minotaur, who lurks below the gym floor. Theseus is reincarnated here as Priapus, the setter for Athens Baptist, whose one eye and fruit-filled jockstrap identify him as the Greek god of the phallus, masculinity in its purest form. After defeating a gaggle of mime-like players wearing the mute masks of a Greek drama chorus, the action cuts to Queen Pasiphae, a Cleopatra-Bo Derek hybrid with blonde beaded braids, who suns herself in a checkered onesie beneath a grape-laden trellis. There the conceited queen insults jealous Venus, who Reid Kelley plays with the face of a pug (“Venus, you’re half-shill, half-shell;/A fallen Avon goddess who can’t sell/Beauty to a pig. Your crap lip glosses/Didn’t put me on the throne of Knossos.”). In retaliation, Venus curses Pasiphae to love a bull (“We have our beef! And I am vowed,/Proud Pasiphae, to make you cowed.”). A volley of bawdy puns makes the dialogue’s sestet form refreshingly humorous, the Greek goddess and queen throwing shade in the meter of classic poetry. Reid Kelley plays them both with high-pitched, flat American accents, recalling the “valley girl” tones of not a few Real Housewives.

Mary Reid Kelley with Patrick Kelley, still from Priapus Agonistes, 2013. Single-channel HD video, black and white, sound. 15:09 min. Courtesy of the artists; Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects; Fredericks & Freiser Gallery, New York; and Pilar Corrias, London.

In Reid Kelley’s version, the Minotaur is a pitiable creature, neglected by her parents to aimlessly wander cinderblock corridors forever. Dressed in a flesh-toned body suit and paper shopping bag—with cartoonish eyes, snout and horns poking out—Reid Kelley stalks sand-filled service tunnels, unable to read wall messages scrawled in blood. Her “friends” are the skeletal remains of Athenians she’s forgotten she ate. Hungry only for company and familial acceptance, the Minotaur wonders why she must suffer such a fate: “I’m as beloved as I am unique/And he who calls me outcast is a liar/Sick with envy over my immortal blood!” Reid Kelley suspends her humor for a moment to relish over the strange. The Minotaur, for her, is a metaphor for human beauty, a physical aberration that reflects the dazzlingly diverse perversities of desire.

Kelley’s transgressive project extends understanding for sexual taboos and illicit pleasures still considered incompatible with the aims and interests of present society. As a literary mouthpiece for this tolerance-expanding enterprise, Kelley turns to Algernon Charles Swinburne, the famed 19th-century poet whose classical poems and dramas have fallen into relative obscurity. Swinburne was a notorious hedonist, his drunken escapades the subject of many sensationalistic London paper reports. Tales of barroom debauchery and bestiality may have been invented; they certainly mythologized the Romantic poet, whose sexually suggestive style made him a cultural revolutionary in the austere moral climate of his time. But Swinburne also practiced what Catherine Maxwell has called “literary sadomasochism;” he saw “the transmutative activity of form as a liberating violence, binding and disciplining language and yet also releasing its energy. Form gives language its teeth so that the finished poem is itself a pleasurable violence exerted on the sensibility of the reader.”[1]

Mary Reid Kelley with Patrick Kelley, still from Priapus Agonistes, 2013. Single-channel HD video, black and white, sound. 15:09 min. Courtesy of the artists; Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects; Fredericks & Freiser Gallery, New York; and Pilar Corrias, London.

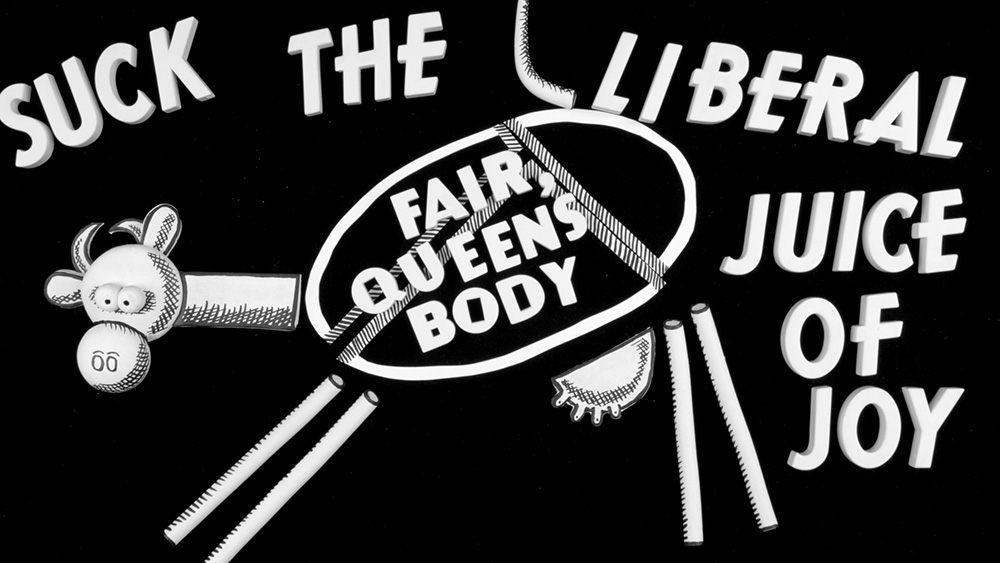

Swinburne’s Pasiphae was never published; the subject of bestiality, and the author’s refusal to voice disapproval for the act through his characters, made it too salacious for print. Reid Kelley recites the recently released dialogue between Pasiphae and Daedalus in her trilogy’s middle film, Swinburne’s Pasiphae. The inventor happily facilitates the queen’s sexual escapades, creating a wooden cow facsimile to enable the bovine seduction. Swinburne’s positive tone gives the reader poetic sympathy for the queen. One the one hand, read to a small and private male audience, Pasiphae’s “cock-crazy” language may have expressed what men felt was representative of women’s genuine yearning for the phallus, a hypersexualized account that serviced male fantasies of female pleasure in domination. On the other hand, this poetic sympathy transgressively places the (male) reader in the position of penetrated Pasiphae, expanding his awareness of the bounds of human sexuality and the liberating possibilities of perverse pleasures.

Mary Reid Kelley with Patrick Kelley, still from Swinburne’s Pasiphae, 2014. HD video, black and white, sound. 8:58 min. Courtesy of the artists; Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects; Fredericks & Freiser Gallery, New York; and Pilar Corrias, London.

Just as the wooden cow becomes a vessel for Pasiphae and her desires, so Pasiphae becomes a vessel for Swinburne and Reid Kelley. The film historically resituates sexual taboos by addressing the Dionysian perversity of classical mythology and culture, where bestiality, sadomasochism, and gay sex are common subjects of interest and desire. In Reid Kelley’s work, as in Swinburne’s, form reflects content; the sting of rhyming poetry is a pleasurable pain that bridges the archaic and the contemporary. By quoting Victorian verse and employing its rhythmic forms, Reid Kelley resists the familiar fetishization of classical culture. Sexual diversity is timeless in her work, a feature not just of ancient Greece or contemporary life, but of Swinburne’s era and all those in between. As James Cahill has argued, “art needs to err—against taste, against conventional morality, and ultimately against its own elaborate devices and affectations—in order to grasp the most fugitive aspects of human thought and experience.”

Mary Reid Kelley with Patrick Kelley, still from The Thong of Dionysus, 2015. HD video, black and white, sound. 9:27 min. Courtesy of the artists; Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects; Fredericks & Freiser Gallery, New York; and Pilar Corrias, London.

The myth’s episodic family drama feels familiar, like a season of Keeping up with the Kardashians. Kelley’s stylistic references are as eclectic as Swinburne’s literary allusions, with the sexually frenzied Pasiphae assuaging her illicit yearnings with pills, alcohol, and the comfort of lifestyle gossip magazines (“I AMPHORA NEW ROMANCE”, one title declares). In the trio’s final film, The Thong of Dionysus, Kelley alights in the alliterative (“Ewer the people implacably plagued by/perpetual pupal putrescence”) and delights in the delinquent: in the labyrinth Priapus falls for the Minotaur’s corpse, drastically altering the myth’s conclusion, marrying bestiality and necrophilia with a lyrical soliloquy of love. The film—and the trilogy—ends in the wine-god’s “Disco Tent”, the maenads and Ariadne dancing aimlessly under the light of a mirrorball. Their closing chorus recalls the “salt sea-storms” of Swinburne’s Pasiphae: “We pass all the nights in our Disco Tent,/In our bedlam we toss and turn,/In truth, we don’t sleep, we just lie on the sheet,/And our Disco Tents never adjourn.”

Whether sailing across the stormy Aegean, strolling through the streets of Victorian London, or dancing in a modern-day discotheque, we are perpetually unfixed by our passions. In an age where religious piety strikes an all-time low, our mores have become apocalyptic hedonism, the existential challenge of ethical self-determination so great it’s been cast to the wind. In Kelley’s work, our current rudderlessness isn’t far from the ancient Greeks’ bacchanalian submission to divine fate or the Romantics’ obsession with death and decay. All we’ve ever had are our desires to guide us, like a thread through the labyrinth of the soul.

—

[1] Catherine Maxwell, Swinburne (Tavistock: Norcote House, 2006), 21.