Kurt Seligmann

First Message from the Spirit World of the Object

May 9-August 28, 2015

Weinstein Gallery

444 Clementina, San Francisco, CA 94103

Was it the Watergate Hearings in 1973, or the Clinton Impeachment in 1998? I can’t remember which. I do remember that sometime during the course of one of them, the national broadcaster announced that the proceedings were “surreal.” I wondered if the general public knew that the word derived from the art world and marveled that a term born in the obscurity of Parisian artistic café society had penetrated into the very fabric of American life. It was proof that art did indeed have an impact.

It was probably due in large part to Salvador Dali, whose public antics fascinated the national press. But there were many players in the surrealist fold, harbored under the rigid control of André Breton, who slashed and burned through his membership much like a strident dictator. Kurt Seligmann was one of these casualties. His expulsion from the ranks occurred after a Tarot reading between the two went south.

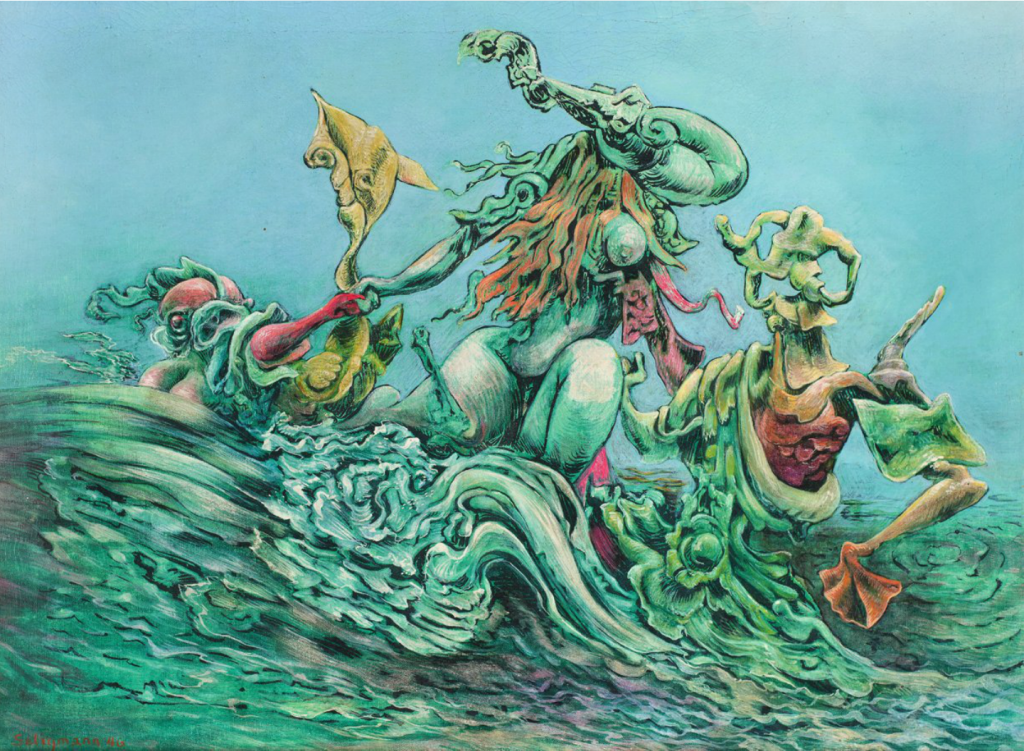

Kurt Seligmann, Amphitrite, 1946. Oil on canvas, 24 x 32 inches. Courtesy of Weinstein Gallery.

Seligmann was a player to be reckoned with in surrealist circles. He was not only an artist of merit, but also one of the world’s authorities on the magical arts, author of, “The Mirror of Magic” (Pantheon Books, 1948). He married well— partnering with Arlette Paraf, a niece of the founder of Wildenstein, one of the great galleries of the era with offices in Paris, London and New York. Their financial comfort assured that the two enjoyed wide travel, allowing Seligmann to explore his interest in the magical arts and tribal crafts of Mexico, the Southwest and British Columbia. Moreover, Seligmann was the first of the European surrealists to land on American shores before the advent of World War II, playing a significant role in securing safe passage to New York for this fellow surrealists, including Breton, where they rode out the war years and greatly influenced American art of the forties and fifties.

None more so than Seligman, who at the behest of Columbia University art historian Meyer Shapiro, provided painting lessons to a young Robert Motherwell. Seligman went on to teach at Brooklyn College from 1953 through 1962, the year he died from an accidental self-inflicted gunshot. He had numerous exhibitions, including participation in most of the surrealist public forays. Yet, Seligmann’s work has flown under the radar in the years since his death. The current exhibition at Weinstein Gallery is his first major American retrospective in 55 years, and a book published by the gallery in connection with the exhibition, “Kurt Seligmann: First Message from the Spirit World of the Object,” is the first monograph on the artist published in English. It can be viewed as a PDF online.

Installation view, Kurt Seligmann: First Message from the Spirit World of the Object at Weinstein Gallery, San Francisco, May 9–August 28, 2015. Courtesy of Weinstein Gallery.

Simply put, the Weinstein exhibition of Seligmann’s work is a revelation. It takes place in a space previously used solely as storage and devoted to exhibition for the first time. Weinstein has been a multi-faceted presence on Union Square for a number of years, notable as the site where a Picasso was purloined in 2011. The 444 Clementina setting is the gallery’s storage space, brilliantly transformed for the current show. The expansive venue houses not only the 50 plus paintings and 11 drawings on display, but also photographs, ephemera and film, providing a richer experience in understanding the artist’s background and significance.

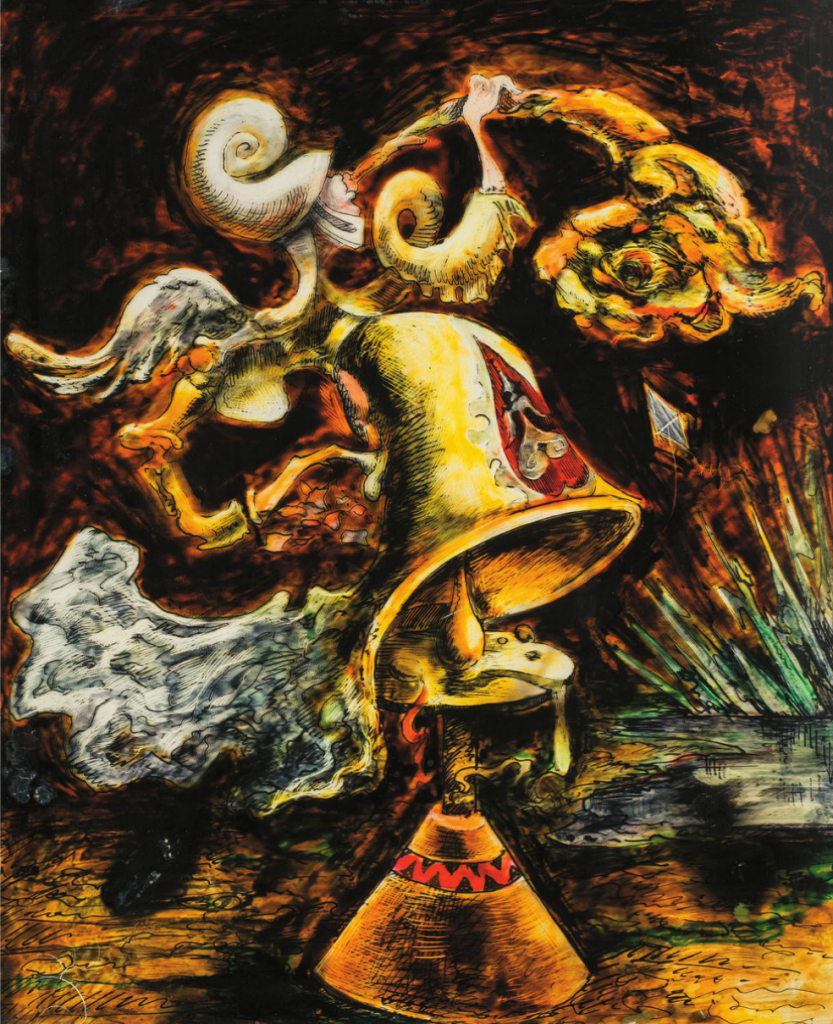

The scope of the exhibition is enhanced by photographs, ephemera and film, but the emphasis of the exhibition is on Seligmann’s paintings, which look as fresh today as the day they were created: not only stylistically, but physically. Whether it’s been the lack of public exposure over the years, or the talents of an exceptional conservator, these works glow. Like many surrealistic works, they contain narratives swathed in a dreamlike state, but many are purely abstract, and several harken more to cubism or biomorphic abstraction than strict assertion to surrealism.

Kurt Seligmann, Sorceresse, 1948. Oil on canvas, 30 x 40 inches. Courtesy of Weinstein Gallery.

The bottom line is that Seligmann was a magnificent painter, with high regard for traditional techniques that have stood the tests of time. The artist employed an unusual manner of working, often projecting light though glass fragments onto canvas, used as preliminary points of departure. It is similar in intent to works by John Cage, who avoided personal preference in favor of chance occurrence, letting subliminal forces determine the course of the work.

Adding to the Seligmann backstory is a symposium sponsored by the gallery, which brought together top scholars devoted to the artist’s life and work. The May 9th event featured Marcia Sawin, the author of “Surrealism in Exile and the Beginning of the New York School,” and Dr. Stephan Hauser, who organized an exhibition of the Swiss artist at Kunsthaus Zug in 1997 and authored the book, “Kurt Seligmann, 1900-1962: Leben und Werk.” They were joined by Stephen Robeson Miller, who serves as an advisor to the Seligmann Center for the Arts in Sugar Loaf, New York, the former residence of the artist. The eighty-four minute symposium can be viewed online on the Weinstein Gallery website.

Kurt Seligmann, Automme Trompette (La Carrillon Muet) aka Trumpet Fur & Kite, 1938. Oil on glass, 20 1/4 x 16 1/8 inches. Courtesy of Weinstein Gallery.

This is a museum quality exhibition by a magnificent artist whose work has taken for granted, rarely been seen in full since the fifty plus years after since his death. Weinstein Gallery specializes in surrealist artists such as Gordon Onslow Ford, Rudolf Bauer, Enrico Donati, Wolfgang Paalen and others, who have been marginalized by the passage of time. Artists come in and out of fashion—their time in the forefront a question of scholarly interest, product accessibility, and theoretical lockstep. Weinstein has made a major contribution by introducing Seligmann to a wider audience through thoughtful presentation of his work, and advancing scholarly insight through sponsorship of a major symposium and producing a significant monograph. The fact that this happens in San Francisco and not in Seligmann’s home state of New York is…so surreal.

Kurt Seligmann, The Age of Reason, 1950. Oil on canvas, 31 1/2 x 39 3/4 inches. Courtesy of Weinstein Gallery.