The Seattle Art Fair has generated a significant buzz for being one of the first instances of an earnest attempt to marry tech money with the art world. While others have tried to wed the boom of over-valuated, venture-capital-infused businesses to speculative contemporary art markets (including last year’s Art Silicon Valley / San Francisco), none have been primarily instigated from within the tech-industry. For the Seattle Art Fair, Microsoft co-founder and private art collector Paul Allen attempts to bring together industries that have been dancing around each other for quite some time. Whether the fair can be viewed as a success or not (or depending on what metric of success one wishes to use), it seems as though the nut of contemporary art being of interest to boy billionaires is finally being cracked.

The fair didn’t come off as overly tech-centric or pandering to the interests of genius brogrammers. That being said, some gallerists who focus on digital art and so-called new media undoubtedly saw an opportunity to reach a much sought-after audience. Interactive sculptures, drone painting performances, and HD videos of 3D renderings attempted to lure collectors by appealing to shared interest in contemporary technology. As fruitful as tapping into a pool of newfound wealth can be for emerging artists working with technology, I can’t help but wonder if abiding by the tropes and strategies of art market economics stifles the potential disruptive qualities of digital art practices.

The Seattle Art Fair might be an easy target for directing these criticisms—it does not, after all, attempt to claim any radical agenda and only loosely promises a unique opportunity for emerging and established gallerists to interface with tech-industry collectors. However, for artists already invested in and responding to digital culture, the Seattle Art Fair might seem like a step backwards. Is a fair made and financially fronted by a well-known technologist in a technology hub the best bet for artists working in digital media to achieve long-term success? Perhaps a more important question could be: has the moment when digital art could confront the status quo of the art world already gone?

I ask these questions, particularly in the wake of the Seattle Art Fair, because I have seen, repeatedly, how digital art suffers from trying to be something that it is not. Over the years, many have tried to bring digital art into the contemporary fold, but few have made it stick in any meaningful way. If anything, private conversations I’ve had with digital artists about their experience with traditional art world dealings have been mostly negative. Though these artists yearn for recognition and participation within a larger contemporary art discourse, most inroads that lead toward that activity appear to contain unforeseen compromises that go against the ethos of their practice. Where some have found great success in translating their concepts from the browser or screen to the gallery, others continue to struggle to appease market demands and traditional methodologies for creating “significant” or salable work.

I suspect that much of this has to do with inherent political and social differences between digital media and the commercial art world. This probably comes as no great shock, but I think that recognizing these differences still gets systematically overlooked by artists and dealers alike. I will resist the temptation to fully enumerate these differences here, but instead will merely say that one primary divide is that digital art wants to be free and commercial art wants to be owned. This gap, though simply phrased, is the most significant problem facing gallerists and dealers wanting to bring together digital artists and the tech industry.

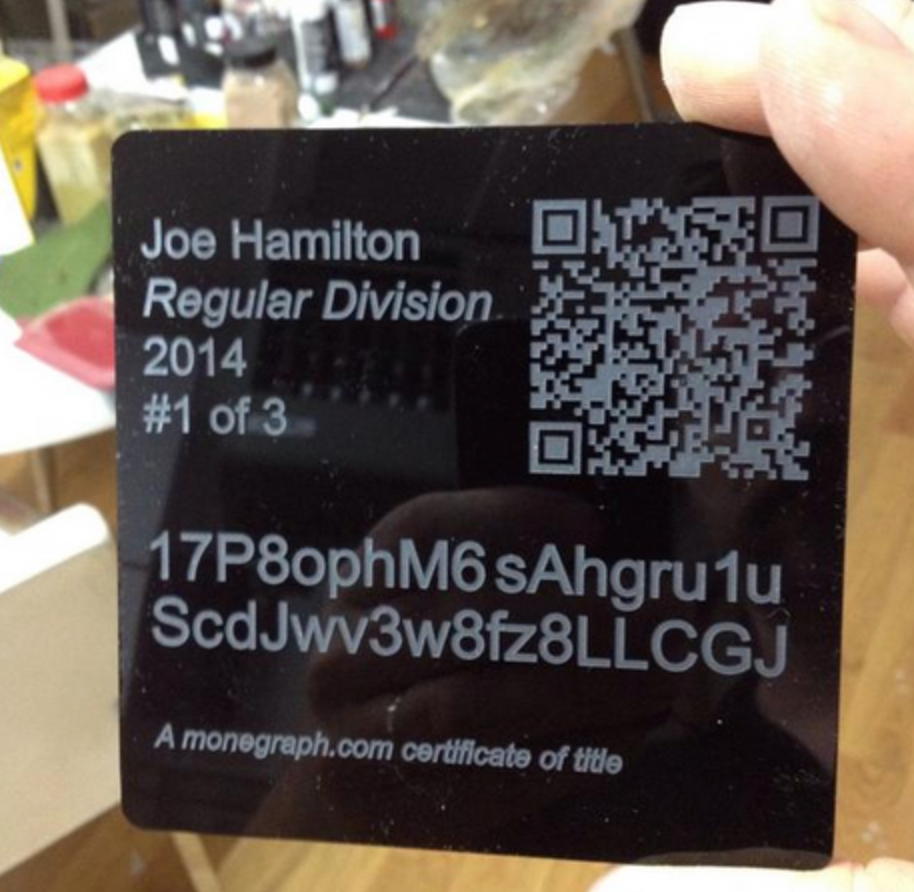

Experimental certificate prototype by Monegraph. Courtesy of Monegraph.

Finding a middle ground where digital art can remain free and where commercial galleries value the propriety of ownership has found some recent headway within the tech industry. Initial attempts at solving some of these systemic problems started bubbling up when Anil Dash and Kevin McCoy teamed up at Rhizome’s Seven on Seven event in 2014 to create a cryptosignature service called Monegraph. Using a cryptocurrency called Namecoin, the duo proposed creating a system wherein artists could authenticate works distributed online against forgery or unauthorized duplication. More recently other companies have also taken up the mantle of attempting to create a system of cryptosecurity to assist artists and creatives to gain more power over their content.

For roughly two years, a company based in Berlin called Ascribe has been attempting to create a magic circle where creators and owners can manage, oversee, and troubleshoot the distribution of intellectual property over digital networks. Started by partners Masha and Trent McConaghy with Bruce Pon, Ascribe is using the blockchain to create what they’ve called an “ownership layer of the Internet.” According to Trent, the blockchain is like a “a database or spreadsheet, just one with very special characteristics.” He added: “Once you add an entry to it, you can’t remove it. Those entries are public and transparent for all to see. As a result, no one owns it—or another way to look at it is everyone owns it.”

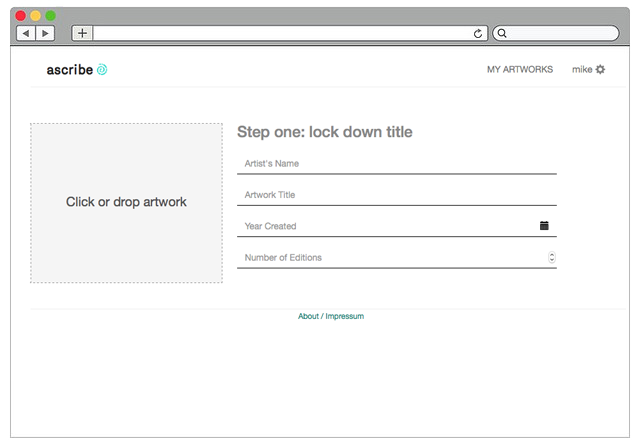

Screenshot from Ascribe.io tour showcasing interface for uploading content. Courtesy of Ascribe.

I spoke with Masha, Trent, and Ascribe’s arts organizer Jazmina Figueroa over Skype several weeks ago to discuss how their product was attempting to create “digital ownership for the creatives of the world.” By allowing users to register work and embed encrypted metadata into assets they wish to distribute online, Ascribe is attempting to give everyday users a legal leg up against a world of endless terms and conditions on proprietary websites.

This is not to say that Ascribe is merely another service for tracking content online. Consumer/user-based web traffic analytics systems have been around for several years, and combined with social media analytic services found on Facebook and Twitter, users have been able to observe extensively the online distribution of their content. But access to this information alone is not sufficient for users to claim ownership of intellectual property. In most cases, users who distribute personal content of any kind have very little knowledge about their intellectual property rights. According to Trent, what Ascribe hopes to do is to “fix the user experience of intellectual property.” By “wielding” the intellectual property more easily through Ascribe, the creators of this service are hoping to give back power to creatives by giving them tools to claim proper attribution.

During MAK NITE Lab on May 31st, 2015, the first digital artwork (a file) was purchased on cointemporary.com for bitcoin using ascribe.io to authenticate and transfer the ownership of the file through the blockchain. © MAK/Nathan Murrell.

Currently, attribution is nearly impossible to trace without tirelessly combing the web manually. Masha told me of one story where a video artist was employing someone on a regular basis to search for bootlegs of her work online and to send cease and desist notifications. Needless to say, the labor of maintaining attribution for most artists who want to prevent unauthorized copies of their work to circulate online, siphons time and energy away from one’s studio practice. Where some attribution can be embedded and traced within the source code of HTML files and/or WhoIs domain registration information, more discreet forms of media like GIFs don’t have this affordance.

As an independent curator and arts professional working with digital artists, Masha had been experimenting with and researching ways of getting collectors more interested in work made and distributed primarily online. She initially found that the main concern for collectors had to do with the provenance of the media. Collectors not only wanted to make sure that the work they owned was genuine, but also wanted to be reassured of the origin of a work. It was not only important that the creation of the work be documented and accounted for, but that the transfer of the ownership be equally legitimate. This is where the blockchain becomes particularly useful, because modifications to an asset’s ownership can be re-attributed at the point of sale, thus preserving its provenance.

Maintaining transfers of ownership and understanding the copyrights held on a work is often the least visible and hardest to access piece of information for any work of digital media. Some long-term plans for Ascribe are to use the blockchain to make ownership more visible for everyday users. Jazmina added how the tool could also be used by communities of makers to support their friends:

“We were brainstorming and wondered if a user found someone’s work [online, if we] could work together to properly attribute media. Someone could find a piece and say, ‘This is me!’ or else help out a colleague/peer . . . There becomes a chance for action for everyone to get proper attribution as opposed to one person trying to control everything.”

By exposing this layer of ownership to everyday users, and allowing those individuals to act/engage with how their content is circulating online, Ascribe starts to outline a potential common ground for commercial art and digital art to coexist. Ascribe is creating what Trent calls a “thin layer” on top of the Internet for proper attribution to exist in a transparent way. Whether an artist decides to financially capitalize on preserving that attribution is left to their discretion. In other words, Ascribe only provides information; it does not provide mandates. All decisions—whether they be cease and desist orders or letters of thanks—are left to the individual who properly owns the work. As a way of encouraging the latter behavior, Ascribe is partnering with Creative Commons France to encourage users to protect their work under a “Free Cultural Works” approved license. In doing so, “ownership” does not have to be synonymous with “commercial.” Trent continued to emphasize the need for digital media to remain open and accessible by discussing ownership as a component of an end goal:

“We’re not really interested in ownership as much as we’re interested in attribution. Ownership is just a benefit of attribution . . . Attribution is unfortunately a bit a of a mouthful, and people don’t understand it as quickly. We don’t have a formed solution yet, but emphasizing the ability to share securely is a really exciting idea . . . When you even say the phrase ‘intellectual property’ it implies something that you own. Property is analogous with ownership. But there’s no agreed upon phrase for ‘intellectual attribution.’ There’s no phrase, but there really should be!”

Perhaps I should argue that Seattle Art Fair isn’t necessarily a step backward, but maybe just a step along the long road of trying to find the best meeting point between the worlds of digital technology and contemporary art. This ongoing process of shaping that middle ground won’t be solved by a simple keystroke and a genius piece of IP, but participation is necessary from all invested members. Designing the better phrases, and better frameworks, can’t happen in isolation from one another, and it is my hope that better alternatives for addressing our problems happen together.