Public Works: Artists’ Interventions 1970s–Now

Mills College Art Museum

5000 MacArthur Blvd., Oakland CA 94613

September 16 – December 13, 2015

In reading the title for the current exhibition at Mills College Art Museum, the words “Public Works” can be interpreted as civic engineering, infrastructure, or utilities services. This tongue-in-cheek play actually pertains to works of art, with a focus on artists who utilize public space not only as a location for display (as might be expected with “public art”) but who also use public space as a forum. Likewise, reading the time frame “1970s–Now” may not make it obvious to some that the exhibition includes all women. But for others, a small amount of deductive logic would clue the viewer in to the fact that the 1970s was the height of the feminist art movement, a significant period for artists who have been vocal, have been concerned, have been active, have been present and who paved the way for younger generations to follow suit. The exhibition does feature all women, though the media materials do not draw too much attention to the point, or focus on feminism as a label. By not drawing attention to this point, the emphasis is solely on the importance of the work itself. It’s a strategic move by curators Christian L. Frock and Tanya Zimbardo to remove gender from the initial discussion and to focus on the more important issues at hand: public space is fodder for discussion, for change, for interventions. However, female gender is not downplayed here, it is actually recognized as a particular voice that carries with it a weight—one that leverages public space in strategic ways whether to challenge the status quo, question male-dominated corporate and social structures, or to make women more present where they are under-represented. The over twenty artists in the exhibition define public space on their own terms, whether it is space as politics, education, transportation, architecture, the body, and even the air that we breathe.

Installation view of Public Works: Artists’ Interventions 1970s–Now. Courtesy the Artist and Mills College Art Museum. Photo credit: Phil Bond

The exhibition is laid out in a formal museum installation, which requires the underlying messages to be drawn out from their historical context, resulting in a kind of sleuthing that empowers the viewer to think more acutely about the works’ implications. This should in no way be perceived as passive, but rather subliminal. This subliminality creates a greater shift in understanding the work on a deeper level—that these works stand to be noticed. They are not “in your face,” but rather imbue the psyche; they put forth, they activate the mind, they inspire, they subvert. Together, the artists form an alliance of groundbreaking moves that jostle comfort zones and push the boundaries of public space, of identity, and what it means to be a woman’s body in public.

Candy Chang, I Wish This Was, 2010–ongoing and photo documentation of I Wish This Was. Courtesy the Artist and Mills College Art Museum. Photo credit: Phil Bond

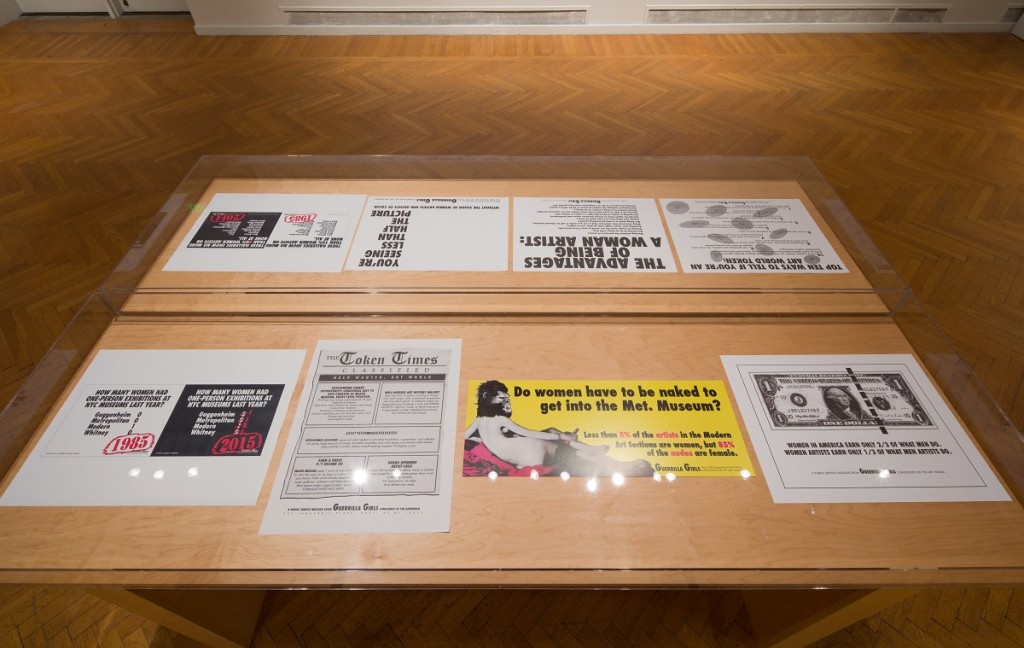

Several artists use the general public as facilitators and messengers of their projects. Candy Chang has been putting stickers, ubiquitously, on buildings in negatively impacted areas since 2010, which read “I Wish This Was ….” The blank space on the sticker invites people to write in their own responses, some of which might read “a school,” or “a medical clinic,” whatever the case may be. The project boldly allows the public to state their wishes directly on the face of gentrification or urban blight. Favianna Rodriguez’s Migration is __________ included an ad taken out in the Oakland newspaper in addition to coloring pages that people could fill in while at the museum. The project also aligned with Rodriguez’s art advocacy entity Culture Strike to collaborate with Mariposas Sin Fronteras and End Family Detention for Visions From the Inside. She worked closely with families detained at the Karnes County Civil Detention Center in Texas, where migrants are held during their process of attaining asylum to enter and stay in the United States. The project focuses on mothers who are there with their children, each suffering tremendous abuses while being incarcerated. Jenny Holzer’s Inflammatory Essays (1979-1982), part of her Truisms series, are list-like free association “essays” in all caps plain italicized font, printed on bright pink, green or yellow solid-colored 17” paper. There are hundreds of phrases drawn from activists and cultural thinkers such as Emma Goldman or Mao Tse-Tung including, “SHRIEK WHEN THE PAIN HITS DURING INTERROGATION,” “CRIME AGAINST PROPERTY IS RELATIVELY UNIMPORTANT,” and the sarcastic “KNOWING YOU HAVE POWER HAS TO BE THE BIGGEST HIGH, THE GREATEST COMFORT.” They were pasted on walls around New York City, as a way to make viewers question their roles in surrounding culture. At Mills they completely cover a wall, so their messages of violence or power extend to the roles of viewers and artists in formal museum settings. Museum discrimination is nothing new to the Guerrilla Girls, whose practice publicly draws attention to the age-old issue that women only occupy only 20% of gallery rosters and one woman, perhaps two at best might have a solo museum show. Their work incorporates, as one can deduce, guerrilla tactics and heavy propaganda distribution to build awareness of the issues that they illuminate.

Guerrilla Girls, various posters from 1985-present. Collection Mills College Art Museum. Photo credit: Phil Bond

Many artists address issues of censorship and government hierarchy in their work. Karen Finley’s 1-900-ALL-KAREN (1998) is an exemplar work that was prompted by the NEA rejection of her work, along with other artists for violating “general decency standards.” Promotional materials for 1-900-ALL-KAREN featured a photo of Finley in the nude, wearing only black high heels, coquettishly posed with a pay phone covering her torso. People could call into the hotline and listen to various soliloquies about life or news. The piece was created nine years after the 1989 Jesse Helms’s NEA attack on Robert Mapplethorpe’s The Perfect Moment, a solo exhibition which included homoerotic imagery at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington DC and Andres Serrano’s Immersion (Piss Christ). Both Mapplethorpe and Serrano were recipients of NEA grants, but the aftermath resulted in the censorship of the work as well as the relinquishment of government support for artworks that are controversial. In the case of the NEA and Jesse Helms, the public is no longer space or a place, but rather a population of people rallying for the cultural protection of a speculative majority. This action censored not only the artists, but also the public’s access to learn from artists who may have exposed them to something new, to something radical. Years later in 2009, Tania Bruguera was accused of discrediting the Cuban government with her performance piece Tatlin’s Whisper #6 (Havana Version), presented at the Havana Biennial. The piece incorporated live testimonial statements by visitors to the fair, prompting widespread public interventions in the streets and on blog platforms, siding with the artist and the participants against suppression. Coco Fusco also used Cuban politics as a platform, particularly the empty public square Plaza de la Revolución also in Havana. In The Empty Plaza/La Plaza Vacia, a single-channel video draws attention to the abandoned architecture interspersed with a Spanish voiceover by Cuban journalist Yoani Sánchez describing various events. The desolation of the setting in this piece draws attention to the “pomp and circumstance” that gilds the lies of government.

Bonnie Ora Sherk, Sitting Still I, 1970, San Francisco. Courtesy the artist.

Other artists take an ethereal approach to questioning our individual roles in the landscape or with surroundings. Bonnie Ora Sherk used the simple act of sitting as a means for inserting herself into places where normally a person would not be. For the Sitting Still Series (1970), Sherk sat in various places around San Francisco, including a garbage-riddled creek run-off area of the Army Street freeway, the financial district, the Golden Gate Bridge, and the San Francisco Zoo. In doing so, she was drawing attention not only to herself, but to the problems that might be plaguing the chosen area. Amy Balkin’s Public Smog (2004-ongoing) considers the absurdity of the atmosphere in the sky as a space for public use through leveraging existing laws that govern the sky. Ironically in reality, where issues of particulate matter and real smog are concerned, the sky is a haven for real estate trading and for shirking air pollution responsibility by the governing agents that occupy the land below the space. One governmental trading entity that Balkin references is the Kyoto Protocol agreement of 1997, which advocated for market trading of sky emissions to alter responsibility for certain regions while simultaneously offering monetary incentives for those who complied with clean air regulations.

Coco Fusco, The Empty Plaza/La Plaza Vacia, 2012. Single channel video projection with sound. Courtesy the artist and Alexander Gray Associates, New York. Photo credit: Phil Bond

Some artists’ work is available for visitors to take with them, to contemplate their meaning or to re-use in their daily lives. Adrian Piper’s My Calling (Card) #1 and #2 (1986-1990) were also available to take and use. Card #1 addresses racial discomfort that people of color face when attending events that might be more populated by whites, or when racial slurs are made: “I regret any discomfort my presence is causing you, just as I am sure you regret the discomfort your racism is causing me.”Card #2 contests the issues of single women attending events by themselves, and states that being alone is not an invitation to be approached: “Thank you for respecting my privacy.” Minerva Cuevas’s, Mejor Vida Corp. (Better Life Corporation) “student identification cards” can be used to get student discounts at museums, transportation, or other services and excursions. Visitors could have their picture taken, and put onto one of these ID cards to keep and use. Susan O’Malley’s text piece You Are Exactly Where You Need to Be (2012) emblazons the museum exterior with its hopeful affirmation. A pedestal at the entrance of the exhibition offers a stack of the same piece in postcard form, so that visitors can take the same sentiment home, or perhaps pass along to others. The word “be” means to exist, to occupy a place, or to continue and remain as before. O’Malley’s work leaves a lasting impression—that we all are part of public space, and that we navigate it, contend with it, agitate and activate it—and if not, we need to be.

Susan O’Malley, You Are Exactly Where You Need to Be, 2012–2015. Courtesy of Tim Caro Bruce, Romer Young Gallery, San Francisco, and Galeria Rusz, Poland. Photo credit: Phil Bond

The exhibition includes documentation, video, interactive works and a catalog. There were two projects that took place in public spaces in addition to the exhibition at the museum. Jenifer K. Wofford: Maxipad: Templum De Mysteriis, Morcom Rose Garden, 700 Jean street, Oakland and Constance Hockaday, You Make A Better Wall Than A Window (http://mcam.mills.edu/events/) Other commissioned works included Susan O’Malley’s mural and postcards, and a newspaper intervention by in the Oakland Tribune of Favianna Rodriguez’s Migration is ____________ campaign.

The full list of artists include: Amy Balkin, Tania Bruguera, Candy Chang, Minerva Cuevas, Agnes Denes, Tatyana Fazlalizadeh, Karen Finley, Coco Fusco, Guerrilla Girls, Sharon Hayes, Lynn Hershman Leeson, Jenny Holzer, Emily Jacir, Suzanne Lacy, Marie Lorenz, Susan O’Malley, Adrian Piper, Laurie Jo Reynolds and Tamms Year Ten, Favianna Rodriguez, Bonnie Ora Sherk, Stephanie Syjuco, and Mierle Laderman Ukeles.