It was a serendipitous occasion for me to have a conversation with Kapwani Kiwanga, not just as a function of being an editor at NYAQ, but also from my standpoint as a roving artist. When we spoke, she was nine hours in the future, in Paris and preparing for her upcoming commission for The Armory Show, while I was housesitting at my mentor’s apartment in San Francisco on a trip that was sandwiched between Christmas in Canada, a solo show in Vancouver and a return to my ancestral homeland, Trinidad & Tobago. We find the time. Time travelling is not abnormal for us. And aren’t we are all becoming accustomed to the requisite time zone gaps, Skype schedules, and increasing connections on a global scale? It seems no longer to be uncommon for us, as artists, to have multiple connections among several geographies, so much so that, perhaps, coincidence is not so surprising anymore as the opportunities and expectations for working become more dispersed across the planet. As it turns out, she too was born in a small city in southern Ontario, went abroad to study, and similarly searches for that slippery place between historical documentation and constructed, fictional delivery systems, oftentimes within a diasporic context. Her use of anthropological research (much more certifiable than my own) is a very useful tool for following her obsessions, no matter which context she finds herself in: be it rural Tanzania, a small village in Poland, an immigration center, an ethnographic museum, or an astronomer’s office.

Kiwanga’s work will be featured in The Armory Show in March 2016, as part of the program, Focus: African Perspectives – Spotlighting Artistic Practices of Global Contemporaries. According to the program’s curators Julia Grosse and Yvette Mutumba:

Artists are contemporary AND painters, performers, Senegalese, Nigerian-born and grown up in London, for example. Meaning: many artists have backgrounds defined by multilayered cultural and social contexts. The young generations, especially, move around a lot—doing a residency in Hong Kong, participating in the Sao Paulo bienniale, attending a workshop in Yogjakarta, and being based in Johannesburg. Through this they become part of a constantly growing international or “global” network, which is even emphasized by digital connections such as social media, Skype etc. Of course, this kind of living shapes the artistic practices in various ways and at the same time reflects the so-much-talked-about “global society” of today.

I’ll just preface this conversation by saying that it’s been interesting for me, personally, to look at the methodology behind your work, because it actually kind of relates to my own work as an artist, being part of a diaspora as well, of Trinidad & Tobago. Especially looking at how you deal with the archive and fiction. It’s all very interesting to me. Do you want to talk about your commissioned project for the Armory? Are you ready to talk about it?

I can talk about it, it’s still evolving and it’s not yet fixed. Basically, the starting point is the idea of gifting, and economies that are established around that, and how relationships are founded around the process of giving and receiving. It’s going to be built around archival footage documents of past and present. I will take some more creative liberties and insert fictive elements into that. It’s really about looking at objects and historical moments in which objects or things will exchange between different people in order to create relationships and networks, I suppose, outside of just pure commerce or capitalism, although it can also fall into that. It’s a broad starting point, but of course, it’s something that, in anthropology, has been an important research area. I am always interested in looking at more popular and everyday expressions of this subject, and historical ones too.

Is the project addressing a particular place?

No, it’s very global, if you can say it that way. Often in my video and performance work, I look at events or even some patterns which are found in different areas, geographically, but also different time periods, so it’s chronologically or temporally quite expansive. Geographically it’s not linked to any particular place.

That’s interesting because many of your projects in the past are very much based in a place or a historical happening in a place and how that’s meaningful in terms of independence and post-colonial development. In light of both approaches, I’m curious how you begin this process of collecting documents to work from.

It’s really just setting out some word searches, starting to read, and then one thing leads to another. My starting point is usually reading academic articles or books or chapters of books, based on questions I’ve already had, I essentially eavesdrop on these conversations that have been happening within academia, or just see how my intuitive questioning has been explored by others. From there, there will be something that presents itself—an object, an event, a person—and that will then set off a chain reaction. So one thing leads to another and makes a network of ideas and interactions.

Could you give a cultural example of gift exchange and how that might expand in a community over time?

I’m not sure if it will find itself in the final work, but of course, there’s an example in the Pacific around gifting, a classic anthropological example of the Kula ring or Kula exchange. It’s the idea that, through giving different gifts, there is a network of relationships and indebtedness, which is held together through geographically distanced spaces, but allows for political and also economic relationships to take place or to be maintained.

It calls to mind Georges Bataille’s The Accursed Share, which I imagine you’re familiar with. That text is really meaningful to me. When I was doing my thesis work in grad school I was thinking a lot about ritual and how there are parallels in anthropological study and contemporary art contexts. There has been so much talk about how the process of a gift, or giving, is integral to a lot of relational art work or social practice, within the turn toward collaborative and publicly engaged work, where exchange is actually at the very core of the concept of the work. I was thinking a lot about how potlatches function in Pacific Northwest indigenous societies and how that might relate to the methods of socially engaged artwork. I’m wondering if there are any threads that you see between what’s happening in contemporary art and also in the anthropological perspective around the gift?

There are of course some great examples of people who are very much committed to social practice in their work, but that wasn’t my intention when I started thinking about this project. It was just to explore past forms of this phenomenon in different geographical and historical areas. What I will be proposing isn’t linked to social practice per se, or participatory practice. It’s more of an exercise in narration I suppose, and the reframing of historical moments and forms or objects in order to look back at them. So it’s a different intention—what echoes are there in everyday life about people creating alternative economies even outside the realm of contemporary art, in daily life?

It’s an important distinction to make and I agree, that it’s more like looking, indexing, and researching, rather than enacting. So, it sounds to me like your Armory project will be more of an installation of archives.

I’ll be working with video quite a bit.

How does this all fit, in your mind, into the theme of The Armory Focus program?

What my understanding of the curators’ approach to global perspectives, generally, is something that resonates. It seems quite obvious: this idea that wherever we are based, or wherever one may have been based before, is not of ultimate importance, and any artist, thinker, or individual, explores and reacts to their environment or to their interest. I’m someone who is very much interested in the African diaspora, because I think it’s an incredibly rich resource, which I don’t always find to be represented as much as I think it could be. I see a lot of absence of African or African diasporic exchange in global discourses. I think the fact that my approach is really interested in culture in the larger sense, temporally, but also geographically, probably reflects that idea of global perspectives that the curators are trying to present in their project and also at Contemporary And (C&). We’ll see how their entire project is articulated in March.

It’s definitely interesting because, here I am coming to this conversation and thinking that the curators are choosing artists who are African or of the African diaspora and who are dealing with African content. That’s just my assumption and I think a lot of audiences would assume that because the program is somewhat framed that way. But how fascinating that, then, you might be liberated from the expectation to present African content specifically. Even if that’s something you’ve done in the past, even if that’s something you identify with. It’s refreshing to hear that you have the latitude not to do that.

And I think it’s something that just depends on the project that comes up at that moment. And it could have been that I wanted to continue on with the project that was specifically founded in an African historical moment, but it just didn’t come up at this point. For example, I could do a project around Maji Maji, which was a historical event that happened in Tanzania, but it was also a conversation with German and French collections, so it was never a single place. There is always this idea that is not forced: it just comes up naturally, of how, of course, one region relates to another through political, economic, or historic exchange. It’s always a space, a particular experience, or a particular moment within a global context. It’s not something that can be extracted from international relations and contexts.

I think that’s very well said, and I believe that, as an artist, your identity is complex and informed by many places. To be pinned down to one narrative of being of Tanzanian descent, Canadian-born and all of this, really starts to shape the expectations of your work. To be able shake that limitation off is actually in some ways more analogous to the reality of the actual economic and political ties between all of these countries. It’s much more complicated than that.

The question of identity doesn’t really come up when I’m working, of course. It only comes up with questions of how does one communicate and mediate one’s work to a larger audience, and then other people are trying to get an entry point from which they attempt to understand something. That’s when I’m reminded that some people are still asking these questions of identity, which for me are not present when I’m thinking about a project. On the other hand, I don’t say I’m not going to work on this or that subject because it might be seen as subject matter that people are interested in because of, perhaps, their family background, and that I’m going to pull away from doing work on Tanzania because part of my family is there. I go where I’m interested in exploring, and it might happen that I’m interested in one area in Tanzania because I visited it and saw something that’s quite interesting, just as it could be that I go to Korea and I’m in Seoul and I see something that interests me and I want to create a work based on that. So it’s really where I happen to be.

Rumors that Maji was a lie . . . , 2014. Mixed media installation at Jeu de Paume, Paris. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Tanja Wagner.

I think that’s really important, and it comes up a lot, especially for artists who are part of a diaspora and do sometimes confront those topics in their work. It seems, sometimes, to be a real barrier to a productive conversation, because of course, as we all know, the artist’s identity isn’t the work, even if they might be related in some way. The two are not equivalent and the work has a life of its own, it has a context of its own. I teach critical writing in the arts in university, and one of the things that is so difficult to address in an artist’s statement or bio is the priority that is given to one’s heritage or pedigree. There is a lot of pressure for artists to self-identify these things, but a lot of it comes down to just the way you might be framed, even beyond your control.

Yeah, but I think that’s a tic that we’ll eventually get over.

Let’s hope so. I think with the kind of work you do, that’s more likely to happen, because you will continue to reject those limitations.

It’s not even a conscious rejection actually, but I suppose yes, it’s not a political statement. I think it’s just about being true to oneself and what interests you.

I am curious about your training in anthropology, and the approach that I’ve seen in your work where you in some ways pose as an anthropologist, but in an art context. Would you call yourself in some ways an unreliable narrator?

No, I think I’m quite reliable! [Laughter]. I think the question rests on how things are read, it always depends on who’s looking and so people will come with their assumptions and their knowledge—things they know and things they don’t know. I think a lot of the work is done by the person who’s receiving and assembling their own narrative. I’m giving a structure, but not telling them how they should interpret and then re-digest what I present.

There are so many variables! You can’t necessarily control what privileged knowledge an audience member might have for your work. Could you give a specific example of when you use a particular tactic to this end where you really want to make clear that what you are doing is possibly a subversion of accuracy or where you’re actually making it very clear that you’re introducing a fictional element to your work?

In most cases it’s just a frame, which is fictional, but most of what I say is true. For example, in my Afrogalactica series, I’m an anthropologist from the future, so the notion of time travel—I’m someone coming from the future to what would be my past, but the audience’s present—has that fictional framework. Most of everything else in that series is true, so my biography or my alter ego is the only fictional part because of what people know or assume. It’s quite rare that there’s much that’s introduced, but usually when it’s introduced in terms of fiction; I don’t try to pass it off as fact. It’s quite obvious because the humor is present and, the absurdity of a situation or of an action is quite transparent.

Time travel is very much something I think about as well and I’m often asking, what are some of the ways we actually use time as a material? I read an interview that you did with Mukami Kuria where you were talking about the Flowers for Africa work, and you mentioned the idea of time folding in on itself. That seems to be something that’s very consistent throughout your work and you’re building up many tactics around that subject. I know you use the term “expanded temporalities” . . .

I work with time, of course, as I mentioned before, as being able to “revisit” the past through documents and archives, but always having this ability to see that no one can ever go back to that time, you can just look back from where we are. So that’s why the archive and the document have always been important for me. There is always this attempt or desire to imagine another future, maybe a continuation of where we are now, also to project into the future, and of course, as we are in our present, we have that kind of temporality present too. For example, there is this very simple magazine fold that I did, in an installation for the South London Gallery last year for an installation called Kinjiketile Suite and in that there were some ads that were for a North American audience and some news which came from Tanzania, so, geographically, I was putting two places in conversation, which shared the same moment in historical time. I also do sound installations, often with voice narration where my voice is talking about a past experience, which is not one that I have lived, but it’s through something I’ve read or some media from the past. I could then talk about a moment that I’ve experienced through my research, or yet again talk about a memory which may be from years ago or whenever. So these kinds of narratives also allow for that temporal slippage. I often use space and emptiness, quite simply, just to allow there to be moments for possibilities, and also emptiness allows space for the unframeable, the things which escape us.

Installation view, Kinjiketile Suite, Kapwani Kiwanga at South London Gallery, London, 2015. Photograph by Andy Keate. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Jérôme Poggi.

You’re going to start to have slippages between yourself and the document by collecting something that is external to you, but also, say, historically accurate. It’s a document of something, but as soon as you interact with it, it’s almost like the observer effect takes place. You start to change it just by looking. It’s not necessarily about your personal memories, but rather the necessary sort of translation that happens between you and a document. Things start to mutate.

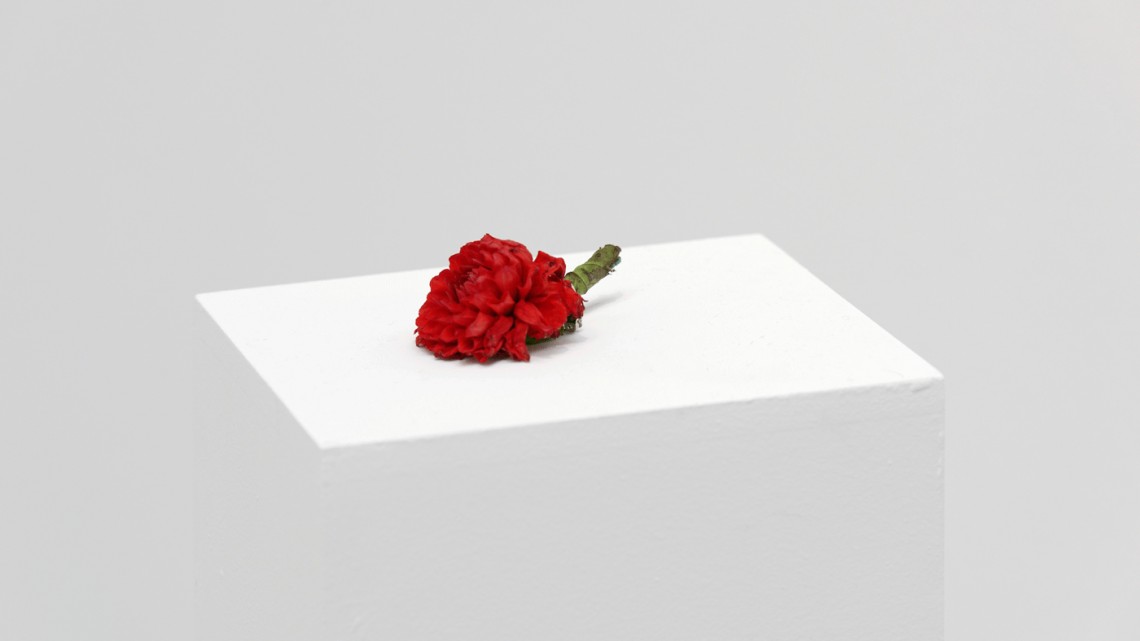

It’s very subjective transmitting experiences. Things are constantly moving and evolving, like in the series called Flowers for Africa in which I reconstruct floral arrangements based on archival images related to independence ceremonies. The protocol for that work is that the flowers are arranged, placed in the exhibition space and then allowed to run their natural course, which is to dry up and wilt away. So the question of fleeting moments; not being able to rigidly set something that may be quite monumental is just very much true to the way I see things as constantly in flux. It’s minute, but then sometimes an immense mutation. You can observe certain areas in a city that change very rapidly, but then there are other places where things seem not to be changing at all, but of course they are. It always depends on what distance one looks at something. I think there’s constant movement.

Flowers for Africa : Uganda, 2014. Protocol written and signed by the artist, iconographic documents. Variable dimensions. Photograph by Aurélien Mole. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Jérôme Poggi, Paris.

As an artist, it’s very challenging to come up with materials that can change over time.

I think that’s why performance is so interesting because it never is the same performance, and I also don’t document performances in terms of video or sound. Although, there may be some photographic documentation, and that’s because I want to foster transmission through people who have seen it and had an experience in the moment. If that was recorded on video or whatever else, something is lost. So, I think performance and actions accept the mutation of the fleetingness of time.

Do you ever actually present your ideas in a non-art context? Would you ever inject anything into an archive? I mean a real, official archive?

There was a project I did last year at the Ethnographic Museum in Berlin, and it was kind of that intention. I asked a simple question when I spoke to people from different sectors of the museum, from the security guard to the store keepers, to the conservators of the museum collections. I asked them, amongst the objects they come in contact with, to describe one of them to me and why it stands out for them. I then went and tried to find those objects in the various exhibition displays. I then made a very simple form based on the same material that the original object was made of. Then I asked the conservators of the appropriate collection to accept my double, I called it, into their collection. I made about 10 of these. Three were accepted into different collections. Those are now in the museum’s permanent collection. In 10 years time, the objects won’t have the same narrative context, things will be forgotten and there will just be these objects made by myself, which have the same name as another object from, lets say, the 13th century. When these objects are in a museum context they are going to be subjected to conservators, and conserving actions, pest control, cataloging and all sorts of things, and my name will be associated with the object as a donor but it is not going to mean much. It will unlikely have any value in terms of art.

I had a feeling you had probably done some work like this, just given the nature of how you work. Did your doubles really look like the originals?

No, not at all. For example, there was a sculpture from the Pacific and it was made from a certain kind of wood, and I just roughly cut blocks from the same wood, so it was really just the material. It’s kind of like these reflections or shadows of the originals. It should be able to stand in for the original object.

In some ways your work lends itself more to these kinds of project-based initiatives. When you do your project for The Armory Show, do you think it will live on past the event itself?

I’ve started on something I’m excited about, and then we’ll see if it develops right away, or if it’s something that I will come back to in six months, a year or two years’ time. I don’t think The Armory will be its end. As you said, I work in projects and they take on these different forms and expand; those could be a performance, a video, it could be sound, or sculpture, and all of these morph with the opportunities I have or what I feel I need to say at that particular moment.