Courtney Malick in conversation with Jos McKain on the occasion of his acceptance to ImPulsTanz, Vienna’s annual and highly selective five-week dance festival, which this year will bring Tino Sehgal to work directly with participants as a mentor and collaborator.

Los Angeles-based Jos McKain refers to himself as a dance artist, and creates movement-based work that weaves choreography, installations, and videos together to address the ways that the problematic relationship between intimacy and media broadly affect individual identities and collective behavior and body language.

Courtney Malick: Let’s begin by you explaining to me what the program is that you have been selected for, which will be taking place this summer in Vienna with Tino Sehgal?

Jos McKain: Every year for the past twenty years this huge festival in Vienna has been held, for which they give out 60 scholarships to dancers. Each year they bring in a different “mentor,” and this year it will be Tino Sehgal. Out of thousands of applicants, I have been selected as one of these 60 participants. Along with the other dancers, I will be working alongside Sehgal and a number of other dance, choreography, and movement specialists from Europe who lead workshops and classes during the residency for its five-week duration. Some of the other choreographers include, Ligia Lewis, whom I recently worked with at the Paramount Ranch art fair here in LA this spring, as well as Trajal Harrell, who did a performance titled, (M)imosa/Twenty Looks or Paris is Burning at the Judson Church and The Ghost of Montpellier Meets the Samurai, which is his newest piece. Vincent Riebeek will also be there, who is in the New York, American Realness dance festival—basically all of the major dancers and choreographers from American Realness will be there, there are over 26,000 participants altogether with 150 workshops and research groups.

Ligia Lewis, Sorrow Swag, 2016. AMERICAN REALNESS, New York, 2016

Wow that is amazing, it will certainly mean a great deal of exposure both for others to get to know you as a dancer and for you to learn first hand from so many others. I’m curious as to why it is called a festival? Is there any point at which you will perform in front of a live audience?

No there isn’t, but basically everyone who goes through this program is very specifically vetted for the entire European dance community. Almost half of the people who are teaching workshops there this year attended the festival on the same kinds of scholarships that I’ve been given last year. It’s also quite an honor, in that, in the festival’s twenty-year history I am only the second dancer from Los Angeles that has ever been selected. There have been many dancers from the Bay Area, New York, Portland, some from Chicago, but only one other participant from LA until now!

That’s crazy! Were you aware that Tino Sehgal would be the mentor this year? If so, were you particularly drawn to the program this year because of the opportunity to be able to work with him?

Yes, definitely. However, it’s funny because I’ve never actually had the opportunity to see any of his work in person, but I know that he is incredibly innovative and thinking really outside the “box” of dance in a way that really resonates to me with my own sort of hybrid “dance artist” practice that I am developing.

True. I mean, when you first said that he was the mentor for this program that seems to be very specifically dance-centric, I was a bit surprised, because, though I understand that his work is very movement and intention-based, I don’t know if I would often characterize it as dance or think of him as a choreographer exactly…

Well he was a dancer before he began his art practice, so you can definitely see that coming through in his current work, but he is not really a choreographer. Again, I think that that duality of his work had to do with why they may have chosen me, because while my work is dance-based, it really exists in that area that is in between dance and contemporary art, and for that reason, I also find myself performing in spaces and contexts that play up to that conflation or grey area.

Tino Sehgal, The Kiss, 2002. MoMA, New York 2003

Right, yes, I have really picked up on that in your work over the past year or so of seeing you perform more and working with you on certain projects. You seem very concerned with behavior and intention as it is funnelled through dance… would you say that is right?

Yes, movement, behavior, and gesture are all at the fore of my thought process, and also in the projects that I have been cast for or collaborated with other dancers on, such as my work with Julien Previeux, Anne Imhof, and Ryan McNamara. This year the festival is specifically focusing on that space that exists between and in the combining of dance and visual art, so it is an ideal time for me to attend. It’s exciting because it seems like this move of dance and choreography into contemporary art spaces is becoming much more popular right now.

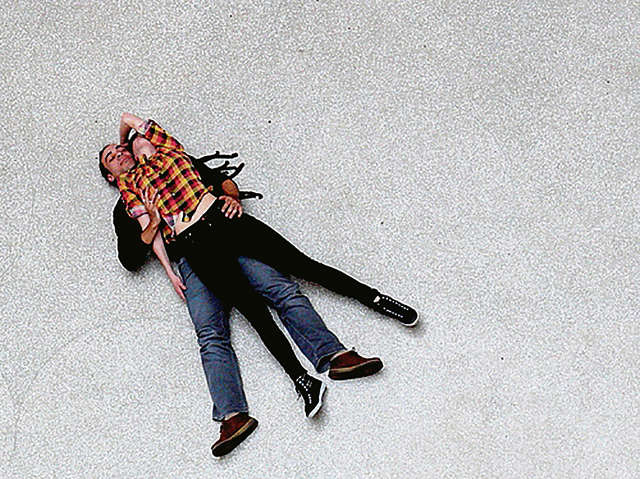

Julien Previéux, What Shall We Do Next?, (video) 2014. Photo credit: Lisa Wahlander

Well, I don’t think that’s an entirely new move…

Really?

Well I think that really began quite a while ago with Yvonne Rainer and her whole way of shifting dance out of a segregated, formal realm.

That’s true. Paul Taylor was also an early pioneer of that move… But I think it’s really having a revival right now in a way that is not necessarily as simplistic as it was back in the ‘70s.

Yes, I can see that… Ok, so, do you know any specifics about what exactly this five-week program will entail? Do you do work other than movement/dance work?

Well, I don’t know everything yet, but I know that in addition to the other dancers and choreographers that will be offering movement workshops, we will all meet with Sehgal as a group everyday and also set up individual meetings with him—so they take the term “mentor” to its furthest extent. The workshops with Sehgal will be specific to a certain content framework that he sets up, but we don’t know yet what that will entail.

Well, with regards to Sehgal’s work, it seems like he would some of the time want and need dancers, specifically, to carry out the actions that he sets up for his works, but other times it seems to be more about type casting and getting the right kind of person, rather than a person with the right set of “movement skills.”

Yes, I think that is probably true, but it’s part of the reason why his work continues to be so compelling regardless of its ephemerality and the fact that he continues to work in the same way, essentially, over and over again. He really highlights the impact of actions and specifically their meaning in relationship to the art world and to the concept of representational space. It’s amazing that he never makes anything permanently physical. I feel akin to his work because I never really wanted to make objects, but as I’ve gotten more involved in the art world, there is obviously a pressure to make objects and work that lasts beyond the performance. His work is great because it raises the question, for me at least, of what it is that defines an action, in and of itself, as a work of art?

Taraj Harrell, Judson Church is Ringing in Harlem (Made to Measure)/Twenty Looks or Paris is Burning, 2009. Judson Church, New York 2009.

Exactly. I mean, for me, I would say that his work proves that it’s the context above all else.

Or the intention?

Well, I am not saying that the context deems an action a good or bad work of art, but, the exact same action that someone would do out on the street, can become a work of art when it is acted out within the white cube, and especially when the overarching framework of that white cube reads “Tino Sehgal exhibition.”

I see that, but I wonder then if that means that his performers become specifically tied to, or an intrinsic part of the work of art itself?

I think so to a certain extent. Because he specifically casts them. If he really wanted the work itself to just be the action alone, he would make instructional art that anyone within the exhibition space could act out. For example some of Yoko Ono’s participatory work, one piece, that I saw last year at MoMA in her 2015 retrospective there, was an entirely empty gallery with a sign outside of its entrance that simply read: “Touch a stranger.” That’s really a conceptual work where the idea of the action is the content of the work, and it can be carried out at any time, by any body, within the exhibition space. Sehgal sort of includes that kind of openness or chance into his work in the sense that if a piece is sold, there is a verbal contract with him and the collector, through which an agreement is reached about the casting terms for future presentations of the work should it be lent to another exhibition. It seems to me that it’s very different for Sehgal to cast a dancer than a non-dancer, non-performer, which he often has. Dancers are so much more acutely aware of their bodies and how they move, etc. For example, if the direction, or action, was simply “sit in a chair,” how would that be carried out differently by a non-dancer as opposed to a dancer?

Well I think a dancer’s response to that direction would be “How?”

Right…

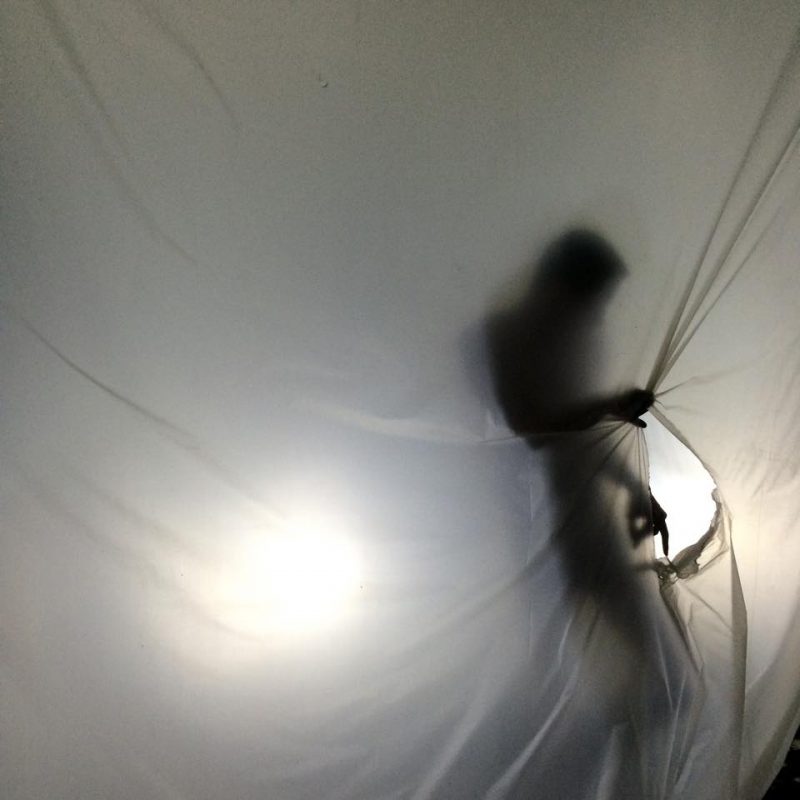

Jos McKain, silhouette l’apres-midi d’une faun, 2015. La SIRA, Paris.

I mean, with regards to this residency and the work that I think we will do with Sehgal there, it will prove to be really intellectually and conceptually expansive in comparison to a lot of the movement-based work that we see in the U.S. or that gets a lot of coverage or attention here. I know that there is such a difference in the overall understanding and appreciation of the importance of work that incorporates the body, of most people, even those outside of the dance or art world, in most places in Europe. For example, there is a piece that I have been formulating and trying to find a venue and outlet for for years now, which is pretty simple and just consists of an agreement that all of the viewers enter into with me when they come to the performance space, wherein they agree that they consent to be picked up me. It’s frustrating because whenever I propose it to people here they don’t understand it at all and just ask, “why?” I always respond by explaining that it is meant to be a sort of exercise through which audiences are asked to really focus on and think about their bodies’ relationship and reliance on gravity, but no one has wanted to take it on yet.

That would be great! Can you expand on how you think an understanding of dance differs here in the U.S. as opposed to in Europe?

Well, first of all, dancers are not just physically trained in Europe, they are conceptually trained and it is considered a much more intellectual and thought-provoking medium than it is, for the most part, here. So, because dancers are bringing more concepts and relevant issues into the ways that they compose performances, audiences there have a more of a direct connection to them.

Yes, that makes sense, it’s too bad that in the U.S. most dancers have to look to pure entertainment careers in order to really make a living, whereas in Europe there are so many more outlets and opportunities for dancers and choreographers who are working more like visual artists.

Exactly–Vienna I think its probably part of the reason that this festival has accepted so few dancers from LA, obviously it is considered pretty much the media capital of the world, and because of that, most dancers that live here work as back-up dancers for big concerts, do music videos, and that kind of thing, which requires technical skill but not always the kind of thought process that they are interested in helping dancers develop. Sadly, it seems like even many of those dancers working and being successful within the U.S. who are able to treat their career like a visual artist would, are still make very entertainment-like dance work that is often less conceptual and challenging to viewers.

Right, they are technically skilled but not putting a lot of content, so to speak, or meaning-making, into their work…? Are there any places in LA where dancers like you, who are working more experimentally and within art contexts, can work and train and develop?

Yes, to me, just dancing well as a backup dancer is not really an art form. It’s pretty hard to find that kind of community in LA. I have begun referring to myself as a dance artist, but that is a small field right now. There is Pieter, which is one place in LA where much less conventional forms of dance are being practiced. Adam Linder is also based here in LA now, so it seems that things are slowly progressing in the same kind of direction that I am working in, but it is still pretty rare.

In my opinion, just painting something well, or being very good at some kind of “artistic” skill in that way, does not necessarily make one an artist.

True, the role of the artist is more of a sort of spirit medium in a way, especially with dancers, they take on a lot of difference energies and forces. I mean dancers are basically witches, or wizards.

Well, I don’t think we’re going to come up with a better closing statement for this conversation than that!

Julien Previéux, What Shall We Do Next?, (video) 2014. Photo credit: Lisa Wahlander