“Jack Wright: A Unified Theory of Painting”

Krowswork

480 23rd Street, Oakland, California

May 2–June 7, 2014

“Resuscitating Reputation,” by John Held, Jr.

When painter John (Jack) Cushing Wright moved to the outskirts of the Bay Area to Inverness in 1959, he found a sophisticated set of settlers, among them Gordon Onslow Ford and J.B. Blunk, who shared his thirst for blending art and life. They were part of a generation ravaged by war, ill at ease with the conservative culture of the era, many of them travelling and residing for a time in Mexico, restless in their search to find harmony between living and its transmission to canvas. After their travels, they believed they found secure and fertile ground in Inverness, far from the roar of the deafening mainstream.

Wright was born in St. Paul, Minnesota in 1919, attended art school in the thirties, and had a “gong” moment upon seeing a certain Morris Graves painting at the Art Institute of Chicago. He entered military service in 1942 and married fellow artist Patty Ordway in 1945. Leaving Mid-America behind, the painter moved his young family (the life-long marriage produced four sons) to California in 1950, where he became a color consultant for an architectural firm.

Relocated to the Bay Area, Wright met Gordon Onslow Ford, a former British naval officer, who had sat in Parisian cafés with the Surrealists at the invitation of Breton, later lecturing on Surrealism at the New School for Social Research in New York to such notables as Pollock and de Kooning. He had a special fondness for Roberto Matta, a Chilean follower of the Surrealists, who made frequent visits to Inverness, and may have influenced his fondness for Mexico where he resided for a time.

Encouraged by Onslow Ford’s tales, Wright moved the family to Mexico for a brief period, obtaining for the first time a spacious studio where he was able to create large-scale works. In 1959, he moved back to Inverness; built a massive studio in the hills overlooking Tomales Bay and Point Reyes. Tellingly, he painted a large glass studio window white, obstructing nature’s bounty to turn inward, concentrating upon his craft and inner visions, searching for a unity in act, thought, and dreams.

Ensconced in the new studio, he joined a community of like-minded artists residing far from the galleries in the concrete canyons of New York. Among them was J.B. Blunk, whose furniture—styled similarly to George Nakashima’s wooden wonders sculpted along the natural grains and burls of the wood—is highly sought after. Philosopher, Zen advocate, and Marin resident Alan Watts, was an influence on the group. Gordon Onslow Ford joined Wolfgang Paalen, Lee Mullican, and Jacqueline Johnson in the staging of an exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Art called “Dynaton.” Other Area painters included John Anderson, Richard Bowman, and Fritz Rauh.

Despite the attempt at forming the group into a united front, a self-inflected habit Onslow Ford acquired through his stint with the Surrealists, the painters of Inverness rather shared an affinity centered on a response to their unique environment and the utilization of dreams in the creative process. In 1989, Fariba Bogzaran—an advocate of “lucid dreaming” in which the dreamer is aware of dreaming—met Onslow Ford. Very much in the Surrealist mold of researching the unconscious, Bogzaran began a theoretical collaboration with Onslow Ford, lasting until the Surrealist painter’s death in 2003. Upon the artist’s death, the Lucid Art Foundation was formed as a beneficiary of Onslow Ford’s estate, and has done much to perpetuate the memory of the painters associated with the region, including Jack Wright, who was the the subject of an exhibition sponsored by the Foundation, “Jack Wright: Luminous Visions,” held earlier this year.

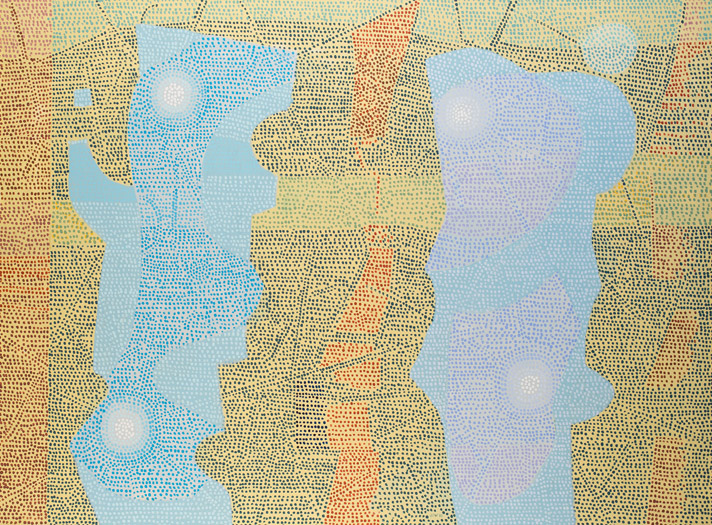

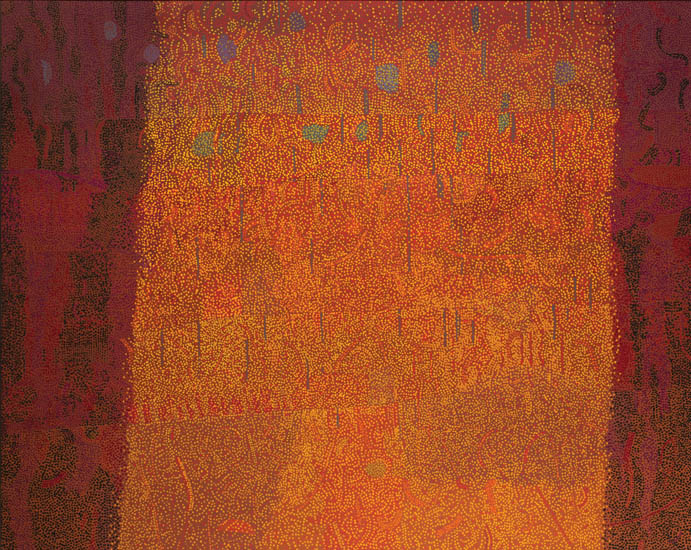

At first glance, one would associate Wright with George Seurat rather than the Surrealists with Aboriginal Art looming as an even more apparent source of inspiration. His use of pointillism, employed throughout most of his career as a painter, became a signature style, modified during various periods to include allied markings, such as commas and slashes. Works in his final years marked a promising new direction, patterned on calligraphy and harking back to the work of Graves and fellow Northwest School painter Mark Tobey.

He began his use of pointillism in 1952, with a masterwork derived from his friendship with “maverick” composer Harry Partch, who made his own instruments, including a set of Pyrex bowls he called a “cloud chamber.” Wright’s response to this work, a painting known as “Cloud Chamber,” set the stage for a lifetime of work, using broad swaths of color filled in by flourishes of square dots applied by brush. We are able to watch him in action, through the foresight of a son, who recorded his father’s thoughts and actions in the film “Dragons on the Ridge,” produced in 1988, and made available for viewing in the gallery.

Wright states in the film that it’s all about mystery, and if the painting lacks mystery, there’s no success in the work. The similarity to Aboriginal work is compositional, yet separates in intentionality. While the native Australians employ dots to map regions and histories, Wright used them to map the mind. In “Dragons on the Ridge,” we watch him charting broad patterns with solid colors and dots added lightning fast—a duel between fore and ground, negative and positive, the yin . . . the yang. Colors are heightened in relation to one another, and it is as a master colorist that Wright excels. In many of the works, the colors seem to extrude from the center, giving the finished work an inner glow.

With early exhibitions at the Walker Art Center (1947) and Betty Parsons Gallery (1948), then at the center of the New York art world, Wright was and could have continued to be a contender. But like the majority of the Inverness milieu, he required a more leisurely pace away from the bustle. Leaving his early successes behind, he was content to pursue his craft and dreams in an isolated setting, painting out the natural world (as he did his studio window) to seek the mystery lurking beyond the surface of things.

As a generation of postwar painters weaned on Abstract Expressionism melts away, we are beginning to witness the rise in reputation of those artists who worked away from the spotlight, neither seeking nor receiving recognition. In their previous exhibition, Krowswork featured the work of ninety-four-year-old local painter Sylvia Fein, garnering a glowing review in the current (May 2014) issue of “Art in America.” Krowswork gallerist Jasmine Moorhead has teamed up with Travis Wilson in this latest exhibition to unfurl yet another blank slate in the modernist canon. In terms of research, presentation, and resurrection of reputation, the current Jack Wright exhibition is a testament to a small gallery making a huge impact.

For more information about the show, visit Krowswork.

Previous contributions by John Held, Jr. include:

“Guglielmo Achille Cavellini 1914-2014″ at the Italian Cultural Institute Gallery, San Francisco

Review: Dohee Lee’s “Ara Gut (Ritual of the Ocean): Mago” at the YBCA, San Francisco