Marco Maggi, “West vs East”

Hosfelt Gallery

260 Utah Street, San Francisco, CA 94103

May 10–July 3, 2014

By Leora Lutz

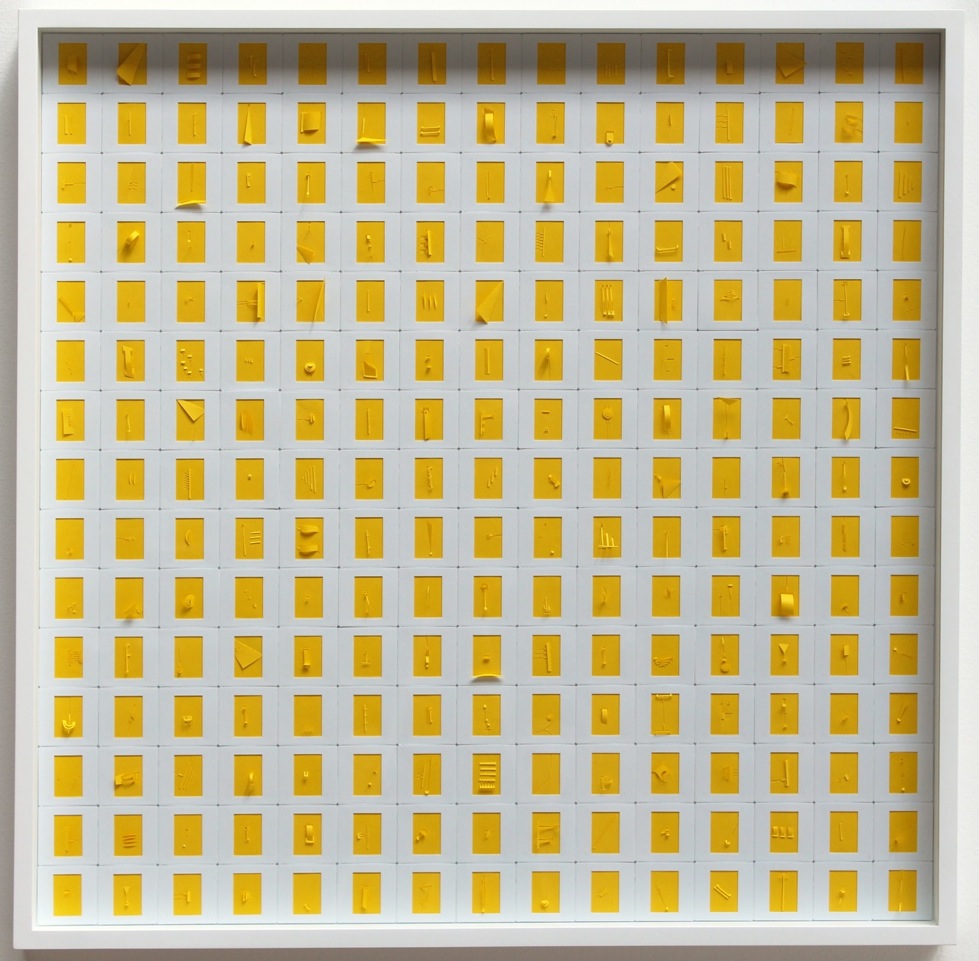

Marco Maggi, “Monochrome (Solar Yellow),” 2014. Cuts and folds on 225 35mm papers in slide mounts, 30 in. x 30 in. Courtesy of Hosfelt Gallery.

The context for Marco Maggi’s exhibition “West vs. East” is geo-political—taking typography, perception, and time into consideration. As the title suggests, juxtapositions are at play: visual and phenomenological; near and far; small and large. By using industrial, mass-produced materials that are painstakingly altered by hand, Maggi prompts a closer look, shifting the viewer’s temporal relationship in order to stimulate consciousness. Many of Maggi’s works are comprised of exceptionally small shapes hand cut from sheets of standard paper, lifted to form a tiny structure that is still attached to the page. Each little shape is approximately one half inch long, with stems that are thinner than toothpicks or squares only one eighth inch in height or length. Each references architecture, from itty-bitty doorways to windows or buildings erupting from larger page foundations, implying that the shapes can be “read,” as if in a book of places.

Though Maggi’s shapes do not share a direct correlation with an alphabet, the structural characters develop into a visual lexicon intrinsic in technological scriptures for an unknown language and unrecognizable typography coupled with his use of everyday objects. Maggi’s use of color—white, black, red, yellow, and blue—correlates with concepts of the ready-made and industrial production. In the “Monochrome” series, Maggi replaces the transparent lens of slide mounts with red, yellow, or blue carved paper. The monochromes are collectively displayed in 30-by 30-inch grids, comprised of 225 slide mounts each. As a singular object, the arrangement is manageable to take in—a field of colored rectangles outlined by white casings. Stepping closer, the intricacy of the objects becomes shocking as the viewer realizes that each pane is a tiny sculpture lifted away from the surface.

Marco Maggi, “Monochrome (Solar Yellow),” 2014. Cuts and folds on 225 35mm papers in slide mounts (detail). Courtesy of Hosfelt Gallery.

I see the crux of Maggi’s aim at consciousness most apparent in the “Monochrome” studies. Juxtaposition between the slides’ original use-form and this new appropriation are markers for disrupting concepts of the archive and the phenomenology of perceiving what is known and what is visually apparent in the present moment. Confusion arises in realizing that what was once transparent is now opaque, and what once held the documentation of an object shifts to an object in and of itself. This conundrum loosely echoes the considerations of early western philosophy, specifically Immanuel Kant’s theories of object-read idealism.1 For example, in knowing that the slide is supposed to be transparent, our view of it is disrupted by the current state it is in, therefore yielding a different and somewhat unexplainable feeling that we are viewing an illusion.

Furthermore, these monochromes bring the realization that certain kinds of technology are becoming obsolete, such as the digital archive replacing slides, PowerPoint replacing the slide lecture, and personal websites and blogs replacing the family album. Whereas slide presentations are viewed in darkened rooms—the images enlarged through projection—the slides here must be viewed close up to see the miniscule paper sculptures jutting up from the tiny pages. So while the big picture of these works feels referential of western philosophy, it is the utterly small nature of the work that seems aligned with eastern philosophy.

Over and over, with a sharp blade, Maggi has cut uncountable numbers of shapes. It is easy to quantify the labor as any number of habits or compulsive inclinations, but if one is to align the making with the teachings of Confucius, then ritual is apropos. Confucianism’s centrality of “li” is analogous with the notion of creating one’s character through performing rituals, or in a sense building, carving, and shaping of the self. Practice of and dedication to li results in “ren,” a state of being that is, simply put, a state of focus and desire for maintaining a positive and unencumbered attitude toward life. Clearly, Maggi’s work can be equated with ritual, simply by the perpetual nature of its making.

Marco Maggi, “Underline,” 2014. Sixty 8 1/2 in. x 11 in. reams of paper; cuts and folds on 8 1/2 in. x 11 in. sheets of yellow, blue, and red Wassau card-stock. Courtesy of Hosfelt Gallery.

Marco Maggi, “Underline,” 2014 (detail). Sixty 8 1/2 in. x 11 in. reams of paper; cuts and folds on 8 1/2 in. x 11in. sheets of yellow, blue, and red Wassau card-stock. Courtesy of Hosfelt Gallery.

The idea of the ritual is also implied in the piece “Underline.” Sixty reams of card-stock paper are aligned side by side on the floor, nestled up against and spanning the length of the gallery wall. There is a striking architectural contrast between the handmade bricks of the wall and the industrially made stacks of paper. In an interview with author and curator Mary-Kay Lombino in 2012, Maggi notes his views on space and scale: “Our illegible world is global and myopic. Breaking time and reducing the scale is my answer. No big solutions or urgent revolutions: my proposal is a homeopathic process. Person by person, step by step, inch by inch.”2 Far away one can view the macro, and upon closer inspection the micro is revealed. In order to closely view the work, one must kneel down to the floor to examine their different folds and cuttings on the surfaces, as if genuflecting. Looking down, one can walk along to read their surfaces. From left to right would be the western way to read, whereas from right to left would the eastern way to read—neither of which is necessarily the correct way. The title of the piece, “Underline” references punctuation that is used as a note in publishing to indicate the use of italics. In the last twenty years with the rise of home computers, the need to indicate italics to one’s publisher is no longer needed, because the writer can now type italic texts themselves, alluding to the obsolete nature of books and the fragile nature of publishing, further iterated in the paper reams themselves. This shift between materials and their temporal function is constant in Maggi’s work.

Marco Maggi, “Points of View (Drawing Glasses),” 2013–2014. Dry point on reading glass lenses on shelf. Courtesy of Hosfelt Gallery.

The other room in the gallery houses a different body of work with textual references that are equally detailed and abstracted, although quite different in their use of drawing as a mechanism for reading. Ideas of analog and mechanical are displayed together in both materials and in the titles of the work. For example, “Points of View (drawing glasses)” are two lenses from a pair of eyeglasses that are etched with abstract lines and displayed on a clear panel raised a few inches from the surface of an underlying white panel. They are lit from the top and cast a shadow beneath them echoing the lines on the lenses. In the Lombino interview, Maggi equates drawing with language: “To draw is very similar to writing in a language that I cannot read: a text with no hope of being informative.” The lenses are now rendered useless for traditional reading and act as a metaphorical lens for viewing the world. If one were to wear these, the act of drawing would be in direct correlation with the eye, marking everything seen through them as a drawing.

Marco Maggi, “Frozen Ream,” 2014. Dry point on 11 in. x 8 1/2 in. x 2 in. Plexiglas block, on black shelf. Courtesy of Hosfelt Gallery.

Across the way is another clear piece, “Frozen Ream.” Looking down into the sculpture is an awe-inducing abstract patterning of lines. Unlike the reams of paper, this one is a cast icon seemingly displayed like a relic for excellent performance given at corporate or industry award ceremonies. Maggi’s work collectively investigates the tiny, the slow, the preserved, and the obsolete. In all, this exhibition is more than one can take in without preparation for the intense realization that the things we take for granted are to be acknowledged as important. A sense of place and inevitability as a player in its development is brought to a monumental fore, which Maggi rewards the viewer.

For more information about the show, visit Hosfelt Gallery.

Previous contributions by Leora Lutz include:

Review: Ala Ebtekar, “Parallax” at Gallery Paule Anglim, San Francisco

Review: Art Market San Francisco

Review: Clare Rojas, “Caerulea” at Gallery Paule Anglim, San Francisco

1 Although Kant’s theories were delving deeply into the transcendental nature of “two-objects,” meaning viewing objects as two-fold; the viewed known, and the unexplainable feelings of said viewing—I think of this idea in a contemporary framework to look at the past and present of Maggi’s specific appropriated materials as the subjects of his work. For further accessible readings on object-read idealism, visit the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy website.

2 Mary-Kay Lombino, interview with Marco Maggi for the exhibition Marco Maggi: Lentissimo at The Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center at Vassar College, January 20 to April 1, 2012.