Forrest Bess, “Seeing Things Invisible”

Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive

2626 Bancroft Way, Berkeley, CA

June 11 – September 14, 2014

By

Courtney Malick

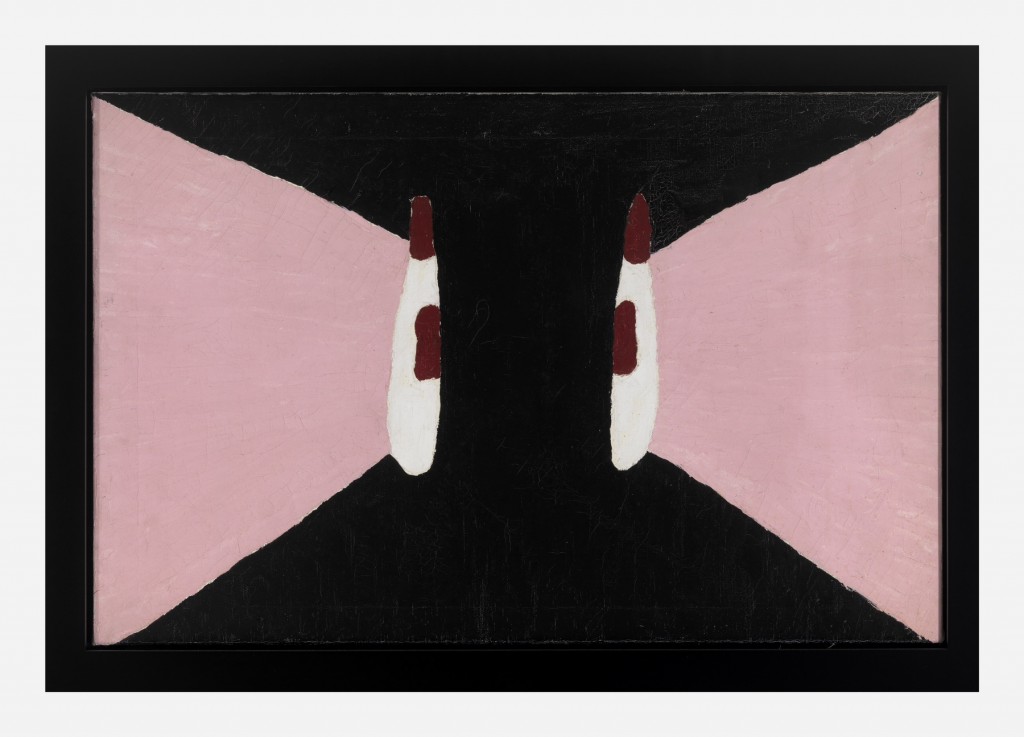

Forrest Bess, “Before Man,” 1952-53.

Courtesy of Neuberger Museum of Art, Purchase College State University of New York, Gift of Roy R. Neuberger

The little known, self-described “abstract primitive painter-fisherman,” Forrest Bess, is an intriguing character in the history of painting, but it is perhaps even more interesting to re-conjure his brief moments of notoriety today, in 2014. Bess (1911-77) lived most of his life in an extremely isolated, small fishing village east of Houston, Texas, where he worked as a fisherman. He had been painting since childhood, but in the early 1950s after a traumatic stint in the military, where he never saw combat but was nonetheless beaten for exposing his homosexual inclinations, his paintings began to take a noticeably symbolic turn. It was then that he began to connect his paintings with the “visions” (not to be confused with the “hallucinations” that he also experienced), that he often saw during the blurred state between consciousness and unconsciousness just before sleep. These visions often referenced specific symbols that he realized related directly to ancient mythology, and as he continued to try to decipher them, Bess began to find that an attempt to balance the male and female counterparts within the human body in order to unveil ancient truths were at their crux.

At this same time he made a rare trip to New York where he met with Betty Parsons who had recently opened her New York gallery where she had begun to show the work of then up and coming prominent Abstract Expressionists such as Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko, among others. She was immediately interested in his work, as it seemed to meld together her interest in abstraction and that of primitive African art, which she also continued to exhibit at her gallery until it closed in the mid 1980s. During their productive working relationship Bess had six solo exhibitions at the gallery and kept in close correspondence with Parsons, as he also did with several other influential figures in his life, including the then widely celebrated critic, Meyer Schapiro. Through his letters Bess’s friends and colleagues began to understand that his fixation with the hermaphroditic state had taken over his interest in painting, and he revealed to them that he eventually went so far as to perform several surgeries on his own penis in attempts to become, what he called a “pseudo-hermaphrodite.”

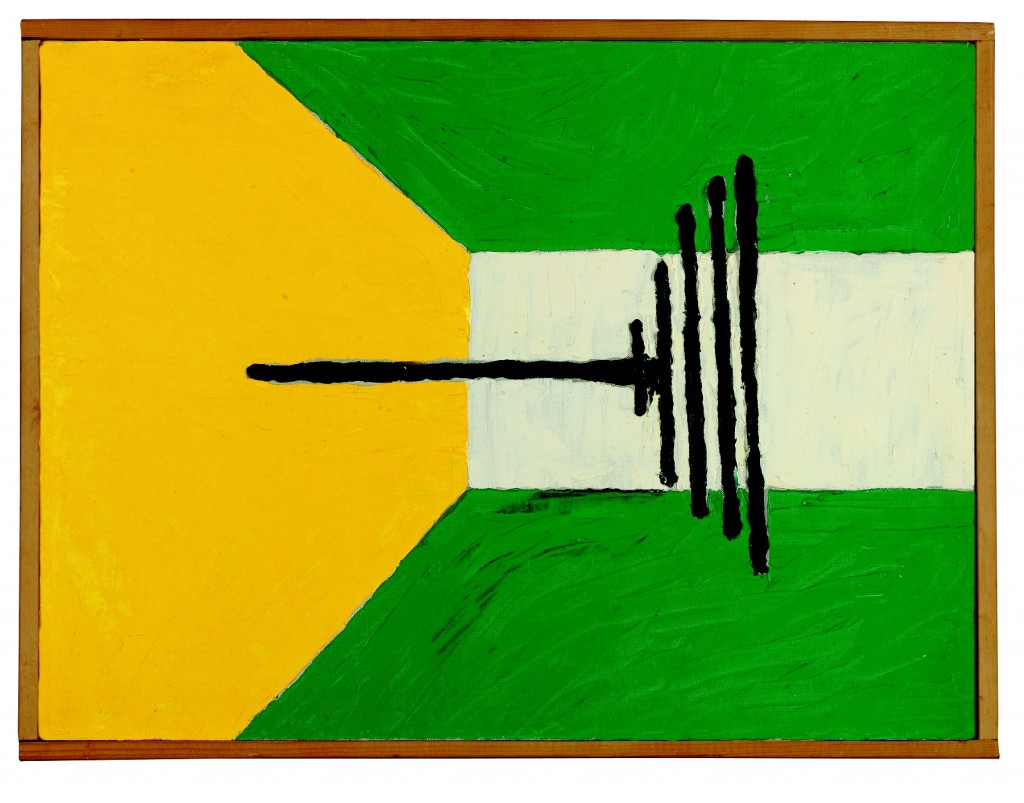

The tension that Bess must have felt in his desire to transform his physical body can be seen in many of the configurations of his canvases that juxtapose severe opposites in color, shape, direction and texture. They are all approximately the same size, around 6 inches tall and 8 inches wide, reminiscent of the size of a box or window one would put their head through. Though when seen together in this retrospective a cohesive language of sorts can begin to be put together through the visual connections from one painting to another, in the 1950s Parsons urged him to try to develop more of a signature style like so many of the other painters that she represented, but Bess felt compelled only to record what he saw in his mind, which resulted in a chronic variety in the body of his work.

This exhibition, which travelled from the Menil Collection in Houston, also includes many biographical artifacts from Bess’s life, such as letters to Parsons, Schapiro and also Dr. Money, a then-prominent physician in the field of gender reassignment, with whom Bess was in contact several times about followup surgeries to extend the manipulations that he had already made on his own genitals. His end goal was for the orifice he had created in the underside of his penis to be made large enough so as to be penetrated by another penis, thus inciting the mythical urethral orgasm through which Bess believed he would attain a state of physical rejuvenation and the cure to aging through the retention of semen. This was a theory that had been widely discussed and experimented with in the 1920s and ’30s, particularly with studies conducted by Dr. Steinach, who first tied the vas deferens in old rats who showed great signs of health improvement afterwards, and later with Chinese convicts, of which there are several photos of men in their sixties whom, after undergoing the surgery looked and felt thirty years younger. This procedure was later translated into today’s vasectomy.

It was only in 1981 when the Whitney Museum of American Art held the first comprehensive retrospective of Bess’s work that the strange story of his life and his thesis on hermaphroditism were exhibited alongside one another, as had been Bess’s wish for most of his life. However, after that point his work seemed to recede back into the shadows, and now again in 2014 comes to the fore with the help of artist and curator, Robert Gober. Gober, who has said he along with many of his contemporaries have been continually influenced by Bess’s work, first organized a small version of this retrospective in a gallery at the Whitney for the 2012 Biennale, after which the Menil approached him to expand the show into a larger museum exhibition and catalog. Today, with the resurrection of abstract, “back to basics” contemporary painting, along with an ever-shifting and complex formation of the notion of gender and identity, these works seem to have a new life and meaning that is perhaps better suited for today’s audiences that they were for those of the 1950s and ’60s.

Though it is difficult to know what one would take from these paintings were they not at this point so closely tied to Bess’s personal theories concerning the body, gender and sexuality. Nonetheless, his story continues to be told, and with it a widening understanding of the deep connections between the two “bodies” of Bess’s work: his painting, and his physical transformation and experimentation, that continue to spread and resonate with younger artists today whose work often explores similar identity-based issues.

For more information about the show, visit the website of BAMPFA.

Previous contributions by Courtney Malick include:

Review: Jonas Lund, “Flip City” at Steve Turner Contemporary, Los Angeles