Terry St. John, “New Work”

Dolby Chadwick Gallery

210 Post Street, San Francisco, CA 94108

10 July–30 August, 2014

By Matt Gonzalez

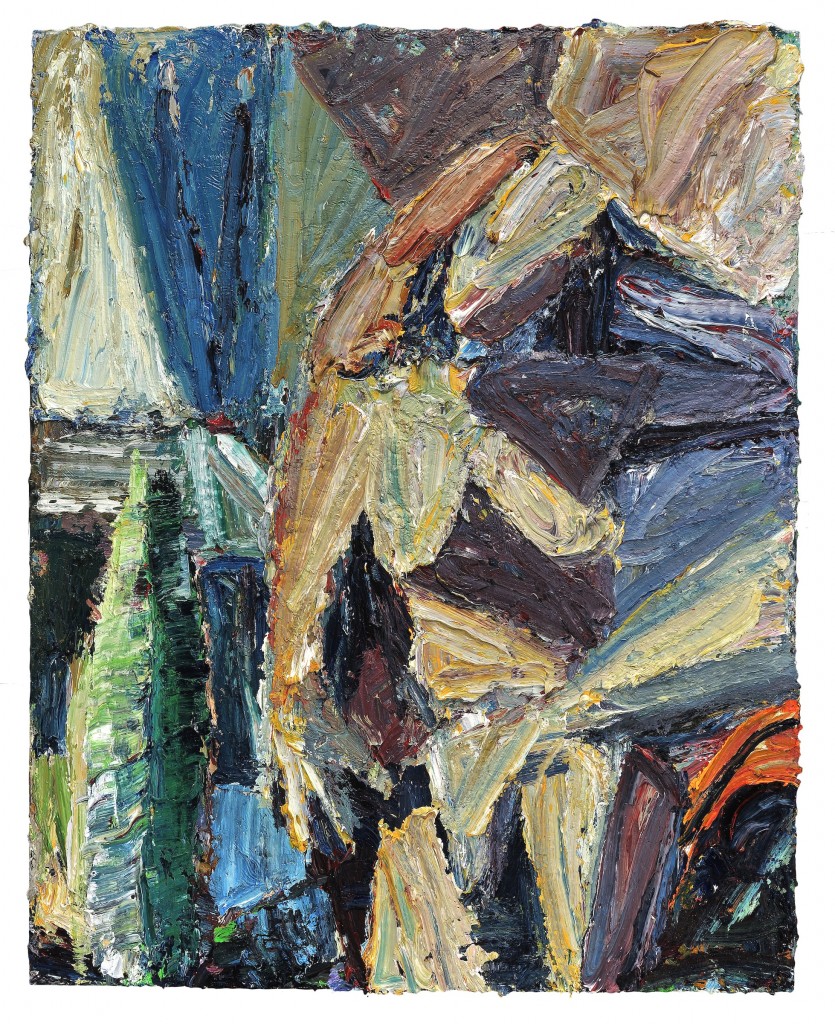

Terry St. John, “Berkeley Marina,” 2011. Oil on canvas, 11 in. x 14 in. Image courtesy of the artist and Dolby Chadwick Gallery.

Terry St. John has been painting for over 50 years. Now an elder statesman of both landscape and figurative painting it can be said unequivocally that he is part of the canon of West Coast painting. But it hasn’t always been this way. As a young man St. John thought he was suited for a life of business administration. Later he ventured into sociology, earning a BA in the subject from UC Berkeley. But it was an encounter during his last semester in college in 1958 with high school friend Henry Brandon, who was studying with Richard Diebenkorn at the California College of Arts and Crafts, that compelled him to pursue painting seriously.

At the time, Diebenkorn was emerging as the dominant painter of the era. His moody and exciting landscape and figurative paintings (which where exhibited recently at the San Francisco de Young Museum’s show “The Berkeley Years 1953-1966”), didn’t fit into any previously known movement or follow any preconceived pattern, although they seemed to derive in part from abstract expressionism.

St. John, whose own efforts had been limited to occasionally painting in his parent’s basement, described the effect these paintings had on him in a 1974 interview with Paul Karlstrom as part of a series for the Archives of American Art at the Smithsonian. St. John said “all of a sudden I saw this guy coming on with this strange, sort of gooky, gunky oil canvases with a figure emerging. I was initially hostile towards it but pretty soon there was something there that was fascinating.” Sculptor and painter Manuel Neri also noted the excitement Diebenkorn had to a generation of artists in a 1977 interview with Beth Coffelt: “God damn it, it was pretty strong stuff. It was just a type of painting we hadn’t seen on the West Coast before. Diebenkorn had a wildness—not the controlled wildness of Hassel Smith, but an out-of-control feeling. Those were urgent times, wild times. He brought us a new language to talk in.”

St. John was so mesmerized by Diebenkorn’s paintings that he started dropping in on classes at what is now the California College of the Arts and he began associating with a number of Diebenkorn’s students. His friend Brandon would offer critiques of his work, no doubt based on critiques he himself had received directly from Diebenkorn. Later St. John met James Weeks, another painter who would also emerge as an important member of the Bay Area figurative movement, and followed him to the San Francisco Art Institute (then the California School of Fine Arts), where he took a painting class with him in 1959. The studio class of ten students was St. John’s first foray into formal art studies. Concerns about space, color, form, and composition predominated his art practice. Both through his studies with James Weeks and later in drawing sessions with another Diebenkorn student, Bruce McGaw, St. John began to work the figure in a way that placed him directly in the lineage of Bay Area figuration, an association that persists today and is apparent in his current exhibit of Dolby Chadwick Gallery work.

The Dolby Chadwick Gallery show, titled simply “New Work,” showcases large figurative oil paintings, two small oil landscapes, and eight of St. John’s loose ink figure drawings. To be sure, it is not a retrospective, as most of the larger work is from the last two years and highlights work he has made in both his Berkeley studio and one he keeps in Chiang Mai, Thailand, for a few months of the year. Most of the work was made after St. John’s 2012 heart surgery, which left him in a coma and nearly resulted in his death.

Despite St. John’s own belief that it was Weeks who was his most influential teacher, his indebtedness to Diebenkorn cannot be understated. St. John uses diagonal lines, partitions his landscapes in much the way Diebenkorn did, and renders the figure with a particular emphasis on light and tonal elements. Weeks shapes were different. He preferred to use parallel forms in his paintings and in that sense was more classical. St. John also notes that Diebenkorn “was fussy about color,” meaning that he paid close attention to it. And like Diebenkorn, and unlike Weeks, St. John never allows a single color to unbalance a painting. He insists that a dominant color in one part of the composition balance elsewhere, although that second color placement is often mixed with others making its presence slight.

Terry St. John, “Relaxed Woman,” 2013. Oil on canvas, 60 in. x 48 in. Image courtesy of the artist and Dolby Chadwick Gallery.

Over the years as they met at various openings, St. John formed an acquaintanceship with Diebenkorn. Later, as a result of St. John’s work at the Oakland Museum, where he landed a job as an assistant curator (after holding jobs bottling water, moving furniture, as a merchant seaman, and as a letter carrier in Berkeley), he attended an opening party at Diebenkorn’s daughter’s home celebrating an exhibition of the artist’s paintings at the Oakland Museum. In a poignant expression of mutual admiration, St. John recalls his wife informing him one day that Richard, or his wife Phyllis, had called the St. John’s home to inquiry about purchasing a small landscape painting that had caught their attention at the Contemporary Realist Gallery in San Francisco. It was a Benicia scene depicting an area of ships and storage silos painted en plein air. St. John recalls that the composition included a strong diagonal element in it. But alas, St. John was going through a divorce at the time and in the midst of the turmoil the sale was not realized.

What is immediately striking about the Dolby Chadwick show are the large figurative paintings, which range in size from 48 in. x 42 in. to 60 in. x 48 in. In each case the figure is clearly recognizable but the heavy impasto obliterates facial detail and adds shadowing elements just underneath the built-up paint that changes depending on what kind of light hits the surface. The highlighted edges bring attention to key elements in the composition. These imposing paintings are laden with paint and give the impression that they are still wet.

This viscosity, a result of impasto painting with large brushes and wide palette knives, has become something of a St. John painting trope. The canvases are distinguished by a thickness that sets him apart from the other painters in the Bay Area figurative tradition. In fact, in some cases it looks as if the oil is mixed directly on the canvas. For St. John, the layering of paint provides texture and shadowing. Art historian Peter Selz has noted that the moodiness St. John achieves is reminiscent of European expressionists Emil Nolde and Chaim Soutine.

Many of the figure paintings include still-life elements within them. There are usually objects on a table or within the studio interior where the model poses. One senses that for the most part these elements are not staged. Windows figure importantly in these works as they allow the interior space to flow outwards and St. John often combines them with a receding architecture within the picture plane to keep the energy of the painting moving. This lures the viewer’s eye from focusing only on the foreground.

St. John’s work is also distinct because of the raking shadows he captures. This affects the tonal qualities of the painting and gives the subjects cubist volume and depth. Raking light, which enters a studio at an angle, can accentuate otherwise mundane objects. Here, it emphasizes the lines of a model’s body and the textures in a landscape or studio interior. The affect on space is dramatic and conveys a sense of mystery by offering a three-dimensionality that wouldn’t otherwise be present. St. John seems to prefer a three-quarter or wider angle of light, which gives the greatest volume and character to objects. These objects, and certainly the model herself, are imbued with more persona as a result.

One gets the impression that St. John paints the figure as if it is a plein air landscape, where the focus is trying to capture a particular moment in time. Light and shadow are crucial to the composition. But in fact, the unique light that is discernible in the oil paintings isn’t depicting a particular moment in time but an amalgamation of light that results from St. John’s studio practice. The models he uses hold a pose for hours and will sit over the course of weeks. When the model isn’t present, he’ll continue to work the canvas looking for a path to a completed composition. Under such conditions it is impossible to finish a painting in a single moment of lighting; what results is a patchwork of competing lighting and tonal elements. A cubist effect results because St. John doesn’t paint out all of the previous lighting sensibilities but rather adds new ones now represented by various blocks and triangles of color and shading. This method also allows for chance discoveries rather than staged renderings. Often St. John uses repeating triangular shapes to enliven the composition. Most of these shapes are not triangles per se, but are closer to an isosceles cone-shape, with two sides of equal length, joined by a shorter third side. Placed on the very top coat of the composition, these recurring shapes reground the painting and compartmentalize the action.

In “Woman Moving” (2013), St. John depicts Buppha, one of the Thai models he has been using since 2010, as a moody seated figure peering over still-life elements in the center of the painting comprised of blue and red. The objects are indecipherable. A tropical plant with thick dense leaves is positioned nearby. It looks like some kind of succulent rendered in thick yellow, blue, and green. It serves to uphold the vertical energy of the painting. Triangle shapes delineate the figure’s hair and also comprise two wing-like shapes hovering above the figure.

In “Woman / Landscape” (2013), St. John set the activity to the left of the composition where he has staged a still-life or far-away object. The painting depicts Solveig, a California model he has been using for eighteen years, in the studio. There is a windowsill with glass panes behind the model. One can discern hills through the window far into the distance. Solveig is leaning against a post, in contemplation. Her knees are bent toward her body as she gazes to her left, away from action of the painting as if to encourage the viewer to move on. The model’s own European heritage seems present here as St. John relates she is of English-German-Polish ancestry.

In “Relaxed Woman” (2013), a woman, presumably Solveig again, sits with her legs crossed and tilts her head slightly. A red or plum color triangular shape appears again with a dash of brown in it. The heaviness of paint and vibrancy of colors including red, blue, and green, animate the figure with vitality. The impasto adds dynamism highlighting certain parts of the body. Triangle forms reappear here.

Some of the paintings in the Dolby Chadwick show were completed in Thailand. While living in Chiang Mai, St. John generally works two days a week with a model. Thereafter he reworks the paintings when the model isn’t available. The goal, of course, is to strengthen the painting. He will look at the painting in different light trying to ascertain its weaknesses and also consult his library of books for inspiration, looking for ideas that might be pertinent to his own focus. The painting can’t stray away from the model, however, lest it become disconnected from its subject. With each session the composition generally gets tighter. If it doesn’t St. John switches the pose, obliterates the figurative elements, and begins anew.

Terry St. John, “Woman / Landscape,” 2013. Oil on canvas, 60 in. x 48 in. Courtesy of the artist and Dolby Chadwick Gallery.

After struggling for years with Thai custom officials who delayed the arrival of paints shipped from California, St. John has finally settled on Chinese paints he can obtain in Chiang Mai. They are manufactured by a Shanghai company that sells a student grade paint that he manipulates to get the effects he wants. But there are two drawbacks: First, the paint is packaged in tubes, rather than the cans he prefers. This occasions him to stop his work to cut them open, perhaps three of them at a time, to replenish his palette. And while the delay may seem slight, it can be enough to lose a moment of inspiration. The second problem is that the Chinese oils dry faster, which makes it harder for St. John to paint wet into wet easily. This is a technique he often employs and which his California paints allow him to confront with a canvas that’s still “nice and juicy the next day.” Despite these obstacles, there are advantages. St. John compliments the natural light which filters into his studio in Thailand from atop the twenty-four foot high ceilings, from the indoor/outdoor concrete studio structure which has carved out window spaces, without glass panes, just beneath a corrugated tin roof.

The eight ink drawings in the show, ranging in size from 22 in. x 15 in. to 17 in. x 14 in., depicting nudes and studio interiors, showcase St. John exploring tonal elements. Here, the model holds a 20-minute pose so the finished product does, in contrast to the oils, capture a particular moment. To execute the drawings, St. John utilizes a Speedball cartooning pen with a metal nib. It’s a calligraphy pen with a tip that looks like a fountain pen that allow delicate fine lines, crosshatching, and uniform line drawing. It’s rather old school, so he has to dip the pen into the ink source frequently with each dousing of the pen lasting for only a single long line, in some cases, two. The pen allows broad or fine lines with the same point simply by adjusting the pressure applied or angle as it strikes the paper. St. John uses an ink manufactured in Japan, a type often generically referred to as India ink. It is indelible; it doesn’t forgive errors. Once the pen touches the paper, ink seeps into its texture. As a result, St. John uses a thicker standard smooth paper, a watercolor variety, which is somewhat permeable but doesn’t buckle under the pen. The darkness of the ink is dictated by how long St. John pauses with his pen against the paper. Black is black, of course, but in his skilled hand there are innumerable shades.

St. John’s begins his drawing work by testing the pen and establishing the line he will be working with. He then looks for shapes or values he can build from. He resists going too dark too quickly because, once placed, he can’t lighten the tonal qualities of the black. St. John participated in drawing groups early in his career, using precisely this method, hosted by Bruce McGaw at his Albany studio in the mid-1960s, no doubt, further imparting lessons learned from McGaw’s teacher Diebenkorn. Naturally, the drawings have no noticeable texture that contrasts with the paintings—the flat and smooth juxtaposed opposite the jagged and built-up paint.

The current show at Dolby Chadwick also features two landscape oils. The smaller of the two, the “Berkeley Marina” painting (2011), 11 in. x 14 in., depicts a familiar site to St. John and is a fine example of spontaneity and looseness. It’s noteworthy for a bold horizontal brush stroke that marks the horizon line. It’s either a single stroke with gaps in the line caused by the thick paint running over a textured canvas or because St. John returned to the line to add staccato along the single stroke mark. There is urgency as the plein air painter hurries to document the moment before it’s lost. A vibrant purple mass at the top of painting is the focal point with all lines leading to it. It contrasts well with the dark grey and charcoal beneath it. In the foreground, one can discern a boat or perhaps a dock form. In all, there are seven or eight separate color shapes moving toward the upper portion of the picture plane.

St. John’s facility painting plein air is evident here, no doubt the result of his history painting outdoors with Louis Siegriest, a seminal member of the famed California fauvist-impressionist group, the Society of Six, as well as with Lundy Siegriest, Peter Brown and Pam Glover, among others.

The Dolby Chadwick show presents a fine representation of Terry St. John’s mature work. In it one can see the artist coming to terms with himself as he tries to capture and convey his own emotion and attitudes on the canvas. Yes, St. John has a subject that he is ostensibly painting, but at their core, his paintings are about his own engagement with the subject and the personal evocations of sentiment and mood he carries with him into that arena. Space, composition, and tonal values are the tools he utilizes as he makes a foray into these inquiries.

For more information, visit Dolby Chadwick Gallery.

Footnotes:

Oral history interview conducted by Paul Karlstrom with John Saccaro and Terry St. John, 1974 April 30-November 18, Archives of American Art.

Manuel Neri quoted in Beth Coffelt “Doomsday in the Bright Sun,” San Francisco Sunday Examiner and Chronicle: California Living Magazine, October 16, 1977.

Peter Selz, “Terry St. John” reviewing St. John’s exhibition at Dolby Chadwick Gallery, Art in America, October 2011.