San Francisco Bay Area, the Mediterranean of the West, has nurtured its own world-changing cultural renaissance always placing a premium on imagination, ideas, innovation, and risk-taking, with practicality, business development, and publicity/marketing/branding left to the likes of New York and London. So it should come as no surprise that the birthplace of the countercultural sixties, San Francisco, has for years boasted the world’s first (yet little-known) LSD museum dedicated to archiving any and all material evidences of the effects of this vision-inducing chemical on cultural production. The visionary behind this “Institute of Illegal Images” is one Mark McCloud, a photographer, sculptor, painter, art teacher, amateur comedian, and the preeminent collector of LSD blotter paper art (he owns an estimated 33,000 sheets of paper bearing miniature artworks). His archive also includes a collection of LSD license plates (!), rare periodicals, and books having to do with psychedelia, surgical instruments, apothecary bottles, paintings, posters, antiques—the list goes on and on. He has had several art shows of his LSD blotter art, most recently at Ever Gold Gallery in San Francisco. Sadly, Mr. McCloud has twice (1993, 2001) had to prove to a judge and jury that he collects and makes art, not LSD.

Mark McCloud recently talked to V. Vale, publisher of Search & Destroy (1977–79) and RE/Search (1980–present). In 1980 Vale featured Mr. McCloud in a photo spread for RE/Search #1, shot on the roof of Vale’s North Beach apartment building, and he also featured Mr. McCloud in RE/Search #11: Pranks! Visitors come from around the world to visit the LSD museum (email mark@nullblotterbarn.com. No cost; serious inquiries only). Mark McCloud has a complexly humorous conversational style filled with oblique puns, references, and lateral detours, which makes for a challenging interview. Join us for the ride!

Traveling Pig, circa 1990. Courtesy of the artist.

So let’s focus on our goal. My goal is to bring maximum respect—that’s the first goal of the piece.

I’m ready for tar and feathers! I’ve seen it come up every which way!

Well, there are probably three parts to everything in life, and one is the unknown background that brought you to where you are now, i.e., the bothersome details of geography and academic institutions.

Still baffling!

Anyway, I know what people want to know about.

That’s good, Vale, because I sure don’t! What happened to me is pretty standard. Not standard in that it happens to everyone, but every once in a while someone falls through the cracks and has a rapturous moment. That’s all that happened to me: your typical everyday rapture! It took me away from wherever I was headed and pointed me in the direction that I’m in now. That’s a very complicated thing because it’s so fashioned for you alone. And no one goes collectively to rapture. It’s always a naked proposition, like you showed up naked and you go naked. The dream that life becomes is pointed out to you as you’re going along. I think that that was the biggest influence in my life: having a death/rebirth experience that led to rapture. Not an easy thing to recommend, since you have to die to have a death/rebirth experience! I was lucky.

Luck is very important in life. Luck and chance, I’m convinced.

Absolutely. And I think we all picked the right motive to “volunteer” for coming here, and then we have problems processing it. And it’s about getting over those problems and processing them that makes you either a happy, fulfilled person or a frustrated, unhappy person.

I always said everyone is an artist, everyone is a writer, and everyone is a musician, and all that—

Because that’s really the only interplay in the Deus ex machina; the thing is so well designed that the only interplay is the aesthetic. You can get the engine to hum better if your aesthetics are applied, but that seems to be the only interplay there is.

I would say that I started my publishing with one simple goal: to fight the control process. But I think that we’re actually controlled most by our aesthetic.

For sure. That’s it. It becomes a matter of style—the way you conduct your investigation here is entirely up to that. So it is very important, the style you settle on, or choose.

Although that can change. Okay, let’s go back to Mark McCloud, the artist. Here’s my perception of you: I don’t think anybody is without a context. Everybody is attached to some kind of so-called aesthetic traditions, even if they’re more rebellious and lesser-known ones. I only knew you as an artist in two realms. I thought you could be a great actor and comedian, but at least we got some really nice pictures of you in the tabloid RE/Search Number One, in which you’re acting a role.

That’s funny! I always tell everyone I’m a reclining comedian. That I’m too laid back to do standup!

They should just bring a psychiatrist couch on stage and then you should do it.

That’s it! I looked into the reclining Buddha thing a little bit.

You could be the first psychiatrist on stage. Hire some straight man to play psychiatrist while you’re free-associating on a couch.

Yeah, a lot of us are frustrated musicians and stuff, but I’m definitely a frustrated comedian. I really did have that role in school. I was always the class clown. And I spent time working at it. The sense of humor that my mom passed on to me—my dad didn’t have much of one, but mom really has a great sense of humor. I think that’s the stylistic aid that’s been most important. Especially when you have problems with the State. If you don’t have a sense of humor you’re never going to get out of there. So I always retain that. Your sense of humor they can’t really take from you.

[Sings] “They can’t take that away from you.”

Yeah, but you know how hard it is: when you finally have to accept the term, and it’s very open-ended, when you become an artist you declare yourself an artist, and you may not really fit the bill. But it’s the closest word we have for that social role. And I’m very much into the Aristotelian view of art, because I like that arrangement—with a group, with a society, of being a type of pioneer that’s on the outer edge of the society, and your responsibility is to get way, way out there. And then to meet the requirements of the group you show them what you’re up to every once in a while. That clears your social debt. I think that’s a very good arrangement; I’ve never had a problem with that. I think the less socially tied an artist is, the better his ability to employ his aesthetic, maybe.

That’s where the adventure is: it’s on the borderland.

Right, but the artist’s responsibility to the group is very uncertain nowadays.

It’s always Hegelian too sort of—you and I are talking now in just word languages, but there are other languages, all kinds of languages. And artists, I think, expand visual languages or symbolic languages. But then the only way we can process that, or one of the main ways, is through words. And words are always reductionist, and they never totally “nail” anything.

No. That’s the gentlemen’s agreement that makes the place a good place to meet. And I like the parameters that we’ve all agreed upon to use here. If we don’t have a name for the thing we’ll draw a line around it and give it a name, or try to come close to it.

That’s why I liked when conceptual art happened. It was kind of a cop-out in a way that it said—well as I understood it—you don’t have to make any “real” art anymore, you can just speak an idea.

And I was definitely in a place where Nauman went, and he wasn’t there when I showed up, but his trail was very, very evident.

What was that trail? I don’t know much about it.

Just the Bruce Nauman conceptual art approach, that Leo Castelli put forward. It was never Bruce Nauman alone. Bruce Nauman always showed with Stephen Kaltenbach, and Stephen Kaltenbach would do a conceptual group of works and then Bruce would do a conceptual group of works, and Castelli would show them both together. People retained Bruce Nauman’s name in the registry much more than they did Kaltenbach’s. But when you go to UC Davis [where Nauman and Kaltenbach both received master’s degrees] and you get your MFA at Davis, the people that have come there before you leave a strong impression. So when I got to Davis it was all about conceptual art. You didn’t need to speak or draw. If you could conceptualize you were “in.”

Usually that involves some speaking, let’s face it.

Yeah, but very little. I was always amazed by the lack of written requirements at Davis, but if you wanted a degree from Harvard or Yale you had to mostly write your dissertation and not paint it or sculpt it. But at Davis you could be deaf or mute as long as you were “producing” and you passed the evaluations. If they liked what you were doing, it didn’t matter if you could read or write—it really didn’t. The great Bob Arneson, when given a couple of pages of his retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art—they held the publication up as long as they could—when he finally turned in his words it just said, “Words.” And they had to put that in two pages of the catalog. The aesthetics that I liked a lot were like Henry Moore where he says, “The talk I put into the piece, rather than talk it.” So he puts the effort of socializing the artwork right into the artwork, and doesn’t have time to talk about it. And I thought: “That’s a very refreshing idea.”

I guess I don’t truly understand what you just said.

Henry Moore wasn’t a big talker about his sculpture. Whenever someone asked about his work he would say, “Well, the effort I would put into talking about it I have already put into the piece.” I thought that’s really great. You know the difference. That’s why Bob Arneson sending in . . . what’s he trying to do with Words? The words have very little to do with it other than the title. At one point funk art relied upon these comical titles that were usually puns, thus earning the term “funk.” That term came out of the Deaf Club; as it turns out, Joan Brown, and our beautiful Bruce Conner, and Manuel Neri came up with the term one night at the old Deaf Club [1979-1980, San Francisco punk rock venue], back in the ‘50s, and they decided to call it funk art, and Kienholz and all those people were involved. And a lot of the conceptual work I was inundated with in graduate school was mostly about the titles . . . of Bruce Nauman’s From Hand to Mouth casting. A resin casting of his mouth leading down to his hand. A lot of it was based on that—very, very small-word associations to the object. I forget the beautiful guy running UC Berkeley at the time—

Not Peter Selz—

No. You know that Gabrielle, his daughter, has written a book that became a best seller? Did you know her? She was around for a while, a very interesting person, but she’s grown up the daughter of Peter, in quite unusual circumstances, and she wrote a good book. She was here about a year ago doing a reading. We all bought the book to see if we were mentioned. Thank God she spared us. But very interesting people. Peter’s big artists were the beautiful Niki de Saint-Phalle and Jean Tinguely.

Tinguely is huge in my world.

Me too. When in Basel a few years ago at Albert Hoffman’s hundredth birthday, on my day off that’s what I did: I went to Jean’s museum and hung out.

I went there too.

Oh, good, Vale, what a great place. I bribed the guard and he let me sit in that Formula One car they had. It was a Formula One Lotus that I guess he owned. They had it at the museum and I got to sit in it.

Something symbolic there—

All his friends were Formula One racers, his best friends. He was definitely into that. But I love the Jean Tinguely museum, that whole attitude toward the social group, where you’re blacklisted by society for the de Gaulle funeral piece. When de Gaulle died they hired Jean Tinguely to do the Charles de Gaulle funeral piece outside of Notre Dame Cathedral. Inside was the Shah of Iran with Dick Nixon, and Kissinger, and everybody mourning Charles, and Tinguely set up a huge monument outside with the covering on, and as the sun set they pulled off the covering and it was this enormous penis that spewed fireworks and self-incinerated. Of course he was blackballed by all after that, and no one touched him until Disney hired him to do these fountains at Disneyworld in the ‘70s. But for many years Jean Tinguely was blacklisted by all society for this funeral piece. I’ll show it to you when I visit. I’ve got a very rare book with it in there, this awesome piece.

It’s funny because you gave me one of your psychedelic, super bright, Day-Glo-colored sculptures that I called a turtle, and we had a green plant-like sort of Ballardian Drowned World sculpture in the corner for a while that was five feet tall. It was green like some tropical plant, and in my own mind, since I’m of limited knowledge, I had already associated you with the funk art movement, as well as an odd mutant strain of psychedelia, because I don’t know—most of the psychedelia, when you think of art you think mostly of those posters that do tricks with your eyes. I don’t think so much of any painters or sculptors when I think of the psychedelic hippie era. But still, it seems if you’re looking for a cultural continuum, you’re coming out of those and now you’re telling me that in person. Bruce Conner too was tied in with funk art. I remember seeing a show so long ago at SFMOMA.

Yeah, and the beauty of Bruce is incredible. The range of vision he had. I was always amazed by the quality of the artwork. He was like Oracle-tied also, so he couldn’t help but have a huge psychedelic side to his work. I think even one of the most cherished acid test publications is one of Bruce’s from like ‘65. And Bruce has this tremendous influence on funk art, on Kienholz, and that’s really the art we associate with the Beats. You know, other than Bucket of Blood. [Roger Corman film satirizing a Beat “artist.”] But even Bucket of Blood has that little tinge of Conner in it! Or Kienholz, at least. And you know, artists, when asked what sense they would last give up, I think all agree that their vision, it’s the one they’d hang on ‘til the end.

George Segal, I suddenly thought of. I don’t know whether I’d call him part of funk art.

Right, well there is that definite funky side to his work, especially when you look at someone with a sculpture like Manuel Neri whose main body was in plaster and wood and string and materials that were often discarded and not considered art. Then I think Segal fits that bill at least. Aesthetically, partially.

I never thought of looking at artists as compared to the materials they pioneered using.

Sure. David Ireland, the beautiful, local, truth-to-materials artist who in a minimalist approach made it more about the materials themselves. So we’re the lucky ones for getting to come here during a renaissance, and the psychedelics definitely caused a renaissance in the arts. One that you are a big part of, Vale.

Albert Hofmann blotter artwork. Courtesy of the artist.

But we’re talking about you, though. And I don’t know how you even got the idea to make art out of blotter acid packaging—what do you call it?

It’s from being raised in Argentina. You remember that humanity forgot how to make toys right after the Second World War? You know this very well that the toys were thin after the Second World War. We didn’t get any good toys until they remembered, “Hey! We used to make toys!” One of the first little things that caught my attention were these books you would get at the local grocery store. There were these empty books, and then you would buy these gum pieces that came with these pogs. They were like little printed circles of paper or little rectangles and they’d have a general theme to the book like Weaponry of the Second World War. And you’d buy the gum and fill the book with these pogs, and if you were able to complete the whole book you would win the bicycle! So then after a few months of filling your book you realized that they had only made three of the German submarine pogs, and that that’s the one you needed to complete your book, you know?

They rigged the game. What did you call them?

Pogs. It’s a term my kid taught me; when they started using them they called them pogs. But we called them fioritas [sic] when I grew up, and you could gamble with them, you could come to school with your extra ones and then we would stand in front of a wall and, by putting the pog between our top digits, then flick the pog toward the wall. Whichever pog got closest to the wall got all the pogs. It was like the first gambling. It was all about these little pogs. There was no art and everything was dried blood and gray after the Second World War, and then the first colored little things I saw were these pogs. If you completed the collection you got the bicycle! The promise of this vehicle that could take you far! Anyway, that’s what happened to me. From collecting these little pogs when I first came to California and started seeing first the window pane and then later that developed into blotter—when I saw the first blotters I realized, “Now these are the pogs of our psychedelic group, and if you complete the book you win the bicycle!” But that’s really all it was. In my death/rebirth experience, part of the vision was that I was in the environment, kind of like Earth, you know, and I was being observed by Apollo and the rest of the celestial magistrates, and they were commenting on me, saying what I was doing. And part of it was that: about the search for the elements that constituted the total unity of all things. That pattern.

Or at least metaphors for “the unity of all things.”

And the overlaying pattern that entails that. Because when you see the total unity of all things visually it makes metaphysical and mathematical sense. They’re aligned properly, and that’s why the conceptualists, or Castelli, had the vision of containing Bruce Nauman by showing him with Steve Kaltenbach, because Steve Kaltenbach went on to become one of the best psychedelic landscape painters ever. He saw a pattern on nature that he’s been trying to paint for many, many years. It’s very hard to see his paintings because you can’t buy a Steve Kaltenbach. You can only trade time to a blind institution and earn one. He’s one of my favorite living artists.

That’s weird. He’s still alive?

Very much alive, and he’s been teaching art for 40 years at Sacramento State College. This incredibly cool artist. He did lots of time pieces that got buried in buildings. He is a very dynamic artist, check him out. The Art Institute brings him in about once every ten years for a lecture. He’s a very humble—

SFAI brings him in—

We get to see him locally a little, but he’s one of my heroes artistically and personally. I got to spend a couple years with him, tripping with him and studying his views. Very, very interesting, beautiful artist.

Up in Davis?

Up in Sacramento, Davis area.

Your so-called mentors—

Fewer and fewer are alive. Sky dying and then Arthur Lee. All I’ve got left is Vale and Roky.

Very funny. You mean Sky Saxon? I thought you were his patron.

I was his patron and hugest fan, for sure.

I thought you let him live at your house.

Yes, of course. Just such a great artist, incredible person. But also the type of artist who wouldn’t really see himself as an artist, but truly is an exceptional artist and an outstanding person. I still go see Roky . . . huge fan still.

Roky Erickson. And Arthur Lee you were a fan of.

Just tremendous, tremendous fan of Arthur’s, and so sad to see him die the way he did, but I always was interested in what Arthur was writing and performing. The psychedelics have truly caused a renaissance, something we won’t be able to measure properly until we’re much farther away from it.

I’m trying to think of other artists that were associated with that, like Peter Max.

Yeah, and Isaac Abrams is still with us, and Peter is still alive, who put the vision on the Slurpee cup. That’s what Peter did—he put the psychedelic vision on the 7-11 cup. He’s the guy that brought it down to the street level.

Who is Isaac?

Isaac Abrams, a beautiful painter who did the cover of that book, the Masters and Houston’s book Psychedelic Art, when they dosed those hundred artists and studied their paintings. Isaac is still painting in Woodstock and you see his work everywhere, on album covers mostly, like Mati Klarwein, the father of psychedelic art.

Mati Klarwein is? Is he really?

Absolutely. Yeah, and Mati’s church is the church that inspired Alex to make his church, Alex Gray. So it’s really Mati who was the Castalia foundation in Mexico, tripping heavily on the mushrooms and painting, and also at Millbrook. He followed the muse around and was there painting it. He’s really the first guy to take it—other than like people like Henri Michaux who did mescaline investigation artistically.

Yeah, that book Miserable Miracle got reissued recently.

Yeah, I’m so glad, it was so hard to get and Miserable Miracle is such a masterpiece. Our views of mysticism are very, very secluded in our society. The Pope having bought all the evidence and holding it close to his chest in the Vatican. And so then a lot of the mysticism due to our generation has been selected to not be shown to us. The prohibiting of the portrayal of Adam and Eve under the amanita muscaria mushroom, as always was portrayed, became illegal in the late 17th century. Punishable by death or excommunication. And the tango wasn’t legal in the U.S. until 1932, Vale.

That’s amazing.

So the role of society in the arts is something that’s always the pull and tug.

So we have to bring things back to your wonderful psychedelic art career.

You hope to get your volunteering cause done, even though it’s probably impossible, and you try to work on your project, whatever it is you’ve come to do, but if you’re rewarded on top of that with a rapturous experience then wow—you’re very grateful. So that’s the big change in my life that led me toward the arts. I was lost and then I was found. And I think all “found” people are artists.

They say you find yourself by making art.

That’s it. What better way? You can commit every mistake that leads you to not making mistakes without hurting anybody, in the arts.

Mistakes into art, often.

For sure. That’s really what the blotter collection is. One bad idea leads to another!

Are you saying you didn’t make the actual physical art that constitutes the blotter acid art that’s in the frames?

It’s nothing that Duchamp hadn’t taught us. Marcel’s found objects. To me it’s just that. I’ve put the found object in a frame.

And then if you sign it, it’s yours. Duchamp taught us that.

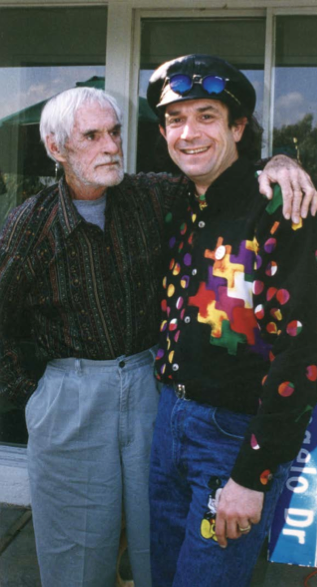

That’s true. Tim offered to sign it all; as Tim was dying and he told me he would take the blame for all of it if I wanted to lighten my load!

Timothy Leary and Mark McCloud, 1994. Courtesy of the artist.

Oh, nice.

Anyway, but yeah, I love that type of artwork, but it’s really that. I was into numismatists also—you know, a coin collector. So I was used to looking at small detailed things and appreciating the way they were made. As the blotter got better I took more notice. Beautiful Nick West, who you will remember, put some hits in Sluggo Number Three and I thought that was such a brilliant move that he also inspired me greatly to collect.

So you collected this art; you didn’t make it.

No—François Truffaut and the other art critic who worked for Cahiers du Cinéma for André Bazin: Godard, yeah, and they were both art critics who after a few years, he said to them, “You know, the good art critics make movies.” And he forced them to make movies. And so then that’s what happened to me: after collecting avidly for fifteen years, I decided to learn more by making some. And then one thing led to another.

And you got some notoriety, fame, whatever the word is, and that brought the attention of the flics [French slang for policemen]. Les gendarmes.

But no, the first blotter show at the Art Institute was also attended by the FBI. They showed up and they said, “Can we photograph this?” And I said, “Sure, this is for you guys, more so than anyone else,” I told them. Because they were the last whores who came to the party!

Whores?

Yeah, the acid party; they’re still trying to arrest us. So I told them, when they showed up in ‘87 at the Art Institute, I said, “Yeah, of course you can photograph it. You’re the guys that don’t understand it yet.” And really, that’s what’s going on. The fliic is tormented by his own demented fears.

Yeah, I suppose so.

That’s why they’re so against it, they think—yeah, and it’s still not over yet. It’s incredible to me: the persistence of erroneous information.

They didn’t understand art; you had to educate the jury and everybody on art.

It’s not an easy one. My poor attorney, you know? My poor, poor attorney.

You said that one of your attorneys demonstrated to the jury that a lot of money had been made, and that impressed people: “Oh, it must be art if it makes money.”

Yeah, they had followed $24,000 into the house. There’s no illegality of receiving money in the mail, and someone had sent me $24,000 cash. They taped it into a magazine and mailed it here. So the DA had opened the packet before it got to me, and they recorded the money, and then sent it in. They couldn’t keep it because it was legal. When they got here the next morning they wanted to know where the $24,000 was. Of course, it wasn’t here; I had already given it to Timmy’s leg operation—from Uncle Scrooge. You know, Uncle Scrooge is mean to the workers and one of them is a father who has a little paraplegic boy and he’s trying to save enough money to get Timmy’s leg operated on. So the money always goes to Timmy’s leg operation, I say! Like when people worry about the future, I always say, “Can we save Weena from the Morlock menu?” Because in The Time Machine Weena is served up to the Morlocks as dinner—Dante’s fascination of the future. That’s her name, the Eloi girl that the Time Machine driver falls in love with.

How do you spell that?

W-e-e-n-a. They only have one name in the future. Like a great artist. When an artist signs his work with one name, like “Rene”—I think: he must be a great artist to go by one name! But a lot of people here, you know—we’re dead guys. We’re what’s happening now so we must already be over.

So how many shows of blotter acid art were you involved in?

As many as possible. But really not all of them were received as graciously as in San Francisco!

SFAI especially.

Yeah, that was the perfect place to unveil it; it’s an understanding audience.

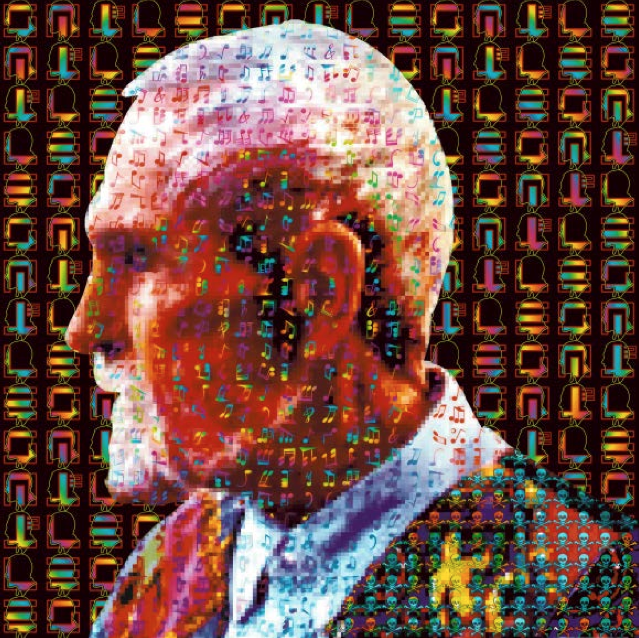

Gorby, circa 1988. Courtesy of the artist.

So the powers that be budgeted a surveillance of you from two apartments for a year and a half. Then they swooped in for the kill after they thought they had enough evidence.

They didn’t understand that the C&H sugar cube guy had had the same problem for years before me! And at my first trial I was wondering where the C&H guy was, because it was a chicken-and-egg kind of defense I had. My defense was, “Hey, I raise eggs, okay, some of them grow up to be bad chickens, you know? But I’m just dealing eggs!” And it was really that: I just made the paper. And I didn’t use Albert Speer’s slave labor in making the paper. No LSD zombies were used in making the paper! And so then my argument was that: “Hey listen, I’m just the art, you know, art is not LSD, LSD is added later to the art!” And so that’s what the good jury of Kansas City, Missouri understood. If they were trying to prove I did the acid they hadn’t done that. That wasn’t enough of a defense to really satisfy my attorney, but that’s all I gave him. You have to give your attorney your defense. I told him it’s really a chicken-and-egg problem. The C&H guy should be here with me because he certainly made the sugar cubes that later got—

He should have been a co-defendant.

My only co-defendant was Nicholas Sand. Nick Sand had made the Orange Sunshine that thirty years before had saved my life, because that’s what I was on was the Orange Sunshine when I had my death/rebirth. And then thirty years later I end up in court with this man I’d never met. Because I didn’t know Nick until the DA introduced us at our trial. They had thrown me together on conspiracy charges with this man, not knowing how “close” they were, because this is the man who made the LSD that flipped me, back then, into the collector.

You got to meet him thirty years later.

And be his co-defendant at the trial where we were both facing two consecutive life sentences! Good way to meet your hero! Yeah, really tough. That’s how life is: it’s full of meaning and irony.

How do you spell Sand?

S-a-n-d, Nicholas Sand. He’s a beautiful man, very beautiful guy. Still alive.

He must be 80 or 90.

No, he’s a kid. Like you, he’s still a kid, Vale! Like you. True, true, wonderful psychedelic pioneer and gentleman. Huge force in the movement, and one of my most admired friends. But he was at Millbrook, he’s self-educated, and he was at the Castalia foundation in Mexico before the LSD, and then he was also at Millbrook with the LSD.

Wow, okay, so then you had two trials in Kansas City.

No, one trial, but facing two life sentences. I was going to kill myself the first night in prison and start my second sentence right away. I mean it! You think I’m kidding. I mean it. So it was an “all or nothing” kind of proposition. I’m just glad that the Kansas City people didn’t buy it.

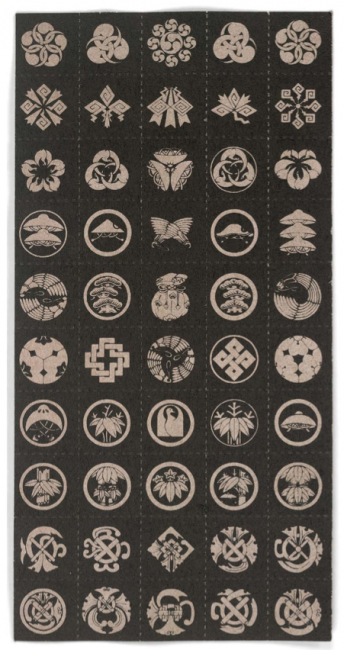

Japanese Crests, circa 1982. Courtesy of the artist.

The lawyer also must have—

He’s the golden one, and his name is Gold, Doran. Doran is the Golden One. If ever in trouble call him and be totally honest and he might take you.

But I thought you told me last time that one of the things that got you off was the fact that you made a bunch of money as an artist.

Well, yeah, we had to answer the DA’s claim that they had followed this $24,000 into the building. And Doran had put the agent in charge at the post office that was in charge of the package [on the stand]: “Is there any law against getting paid in the mail?” And the guy said no. So the jury thought, “Hey cool! This artist does okay.”

Oh! He must be a real artist.

Right. My father didn’t like me being an artist until I got my second National Endowment grant from Ron Reagan—then Dad started to brag about it. That’s how artists are viewed. You don’t want to be an artist ‘cuz you starve to death, but if you make money then they brag about you. But I’m just glad that the artwork has continued to plow forward, even though our archaic government keeps hanging on to rules that they know are not intelligent.

So let’s go back to your art history, so to speak. We all know that there’s no separation between your art and your life, we’re post-Duchampian in that way, but I’m trying to be an archaeologist here. You’ve left behind photos. I don’t know how many of those crazy, wild psychedelic, super bright dayglo colored sculpture things you made, but what happened to them all? Where are they?

You show up naked, and you split naked, and that’s pretty much all you get, Vale.

But at least they were made.

That’s it. To be or not to be remains the question.

Well, you made sculptures—we know you did that.

Yeah, and I recommend that if you’re very intellectual and you’re thinking about your stills from movies all the time, that you get a job, a physical job, like sculpture! You will come home exhausted every night.

It’s physical too.

And I love sculpture for that reason.

Yeah, not verbal.

It’s just so physical. You’ve got to try it at least while you’re in your body.

Okay, everyone: sculpture must be made by all, is our lesson.

Absolutely.

Okay, let’s go back and tell me all the forbidden stuff you never tell anyone, like where were you born?

I was born in Gross Pointe, Michigan. My dad had a really good insurance program at the time that allowed them to move from Detroit, where they lived, to Gross Pointe. So I was born in the hospital in Gross Pointe.

Wait a minute, I thought your parents were Argentinians.

No, no, they were sent there after the Second World War by Edgar Kaiser to put together a car company. But my mom is an Oklahoma Cherokee girl, and my dad is a Golden Glover [boxing prize] from San Francisco. Dad got the golden gloves here in 1941 at the armory there on Mission Street! That’s where they gave you the gloves in those days.

And your mom?

A Cherokee princess from Oklahoma. They met during the war effort out here at the shipyard. So then I was raised in Argentina, but I returned here because it is my home, just one generation kind of separate.

Okay, you said you returned to America at age 12. Now did you ever live in Switzerland?

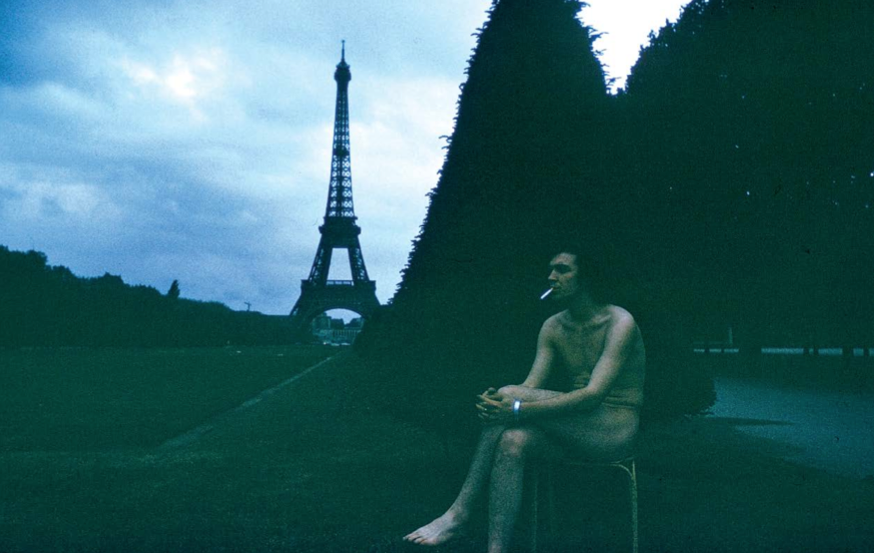

No, but [I was there] for a little intermittent while, not just in 2006 when I went to Albert’s 100th birthday party. [Also] as a student in Paris in the early ‘70s I got around a little—the dream of all artists.

Yeah, it is, to go study in Paris.

In those days it was all about Paris. I really wanted to see the real item, so I signed up at that museum there, École du Louvre, which was just outstanding, and very priceless. The tuition was $20 per year. And it’s one of the finest art history schools in the world; it’s where I decided to do all my art history. Yeah, really great. So I had a pass that got me into every museum in Europe for free, but also allowed me 24-hour access to the Louvre. So I could spend the night in there! And often did. That was the best thing, was to go there, study film, and study the Italian Renaissance, which was my area of interest, Giorgioni being my favorite. And actually spending time with the real thing—the actual item. That’s magic.

Wow, I’ll say.

I insist on that now: the real thing, seeing the actual item, and what that does for you.

Wow, so actually I should have asked you before: surely as a child you drew and—

No. I was a photographer and I was into very little things and close-ups, because everything in Argentina was atrocious then. Every time I looked beyond the immediate periphery or anything further than twelve inches I saw some atrocious thing. I’ll tell you, I was driving in a car as a young guy and when I finally got over the window level and could see over the window I remember seeing—it was like early in the morning and we were out in the country, and we drove by this lake, it’s pretty cold out, and we drove by a corner where unbeknownst to me there was a bus stop, but instead of a bus stop I just saw this line of people lined up, all wearing clothes that didn’t fit them—all dressed at gunpoint obviously—and I didn’t know they were waiting for something. I could just tell that none of the clothes fit them and that if they swapped clothes they would be better off, and that things were really bad. So I kept things really close up as a kid. I was very ill and sickly and feverish, and I was really into the little smudge spot that my head left on everything, and that kind of scale. So I had an ant farm, and I wanted to photograph the eight ants, because I knew them personally so well, I could tell their personalities apart, and I wanted to show that. And that got me into the arts—my first love was photography. I never thought of art or anything like that. It was more that I had a job to do with this project. I only learned about art when I left high school and entered college. I took a course from the beautiful Paul Kos called Conceptual Sculpture as a premed student in Santa Clara, and it really changed my life. But that’s also when I had my death/rebirth experience, showing me that what I thought was called psychology was really called art. So I had to change then.

I don’t think you’ve told me about the death/rebirth experience before.

Yeah, you don’t sit down with buddies and really chew that one out unless it’s called for—and it’s a very intricate thing that involves an infinite amount of time because that’s how long it takes for a dumbass to learn what’s going on. And then when it’s over it was actually a quarter of a second. But no, that’s really what happened to me. So then on that December night in 1971 where by all intents and purposes I fell out of a window onto my kisser, I really fell into what we call the State of Oneness. And there’s nothing like being One with Everything and the understanding that that gives you!