Allen Ginsberg

“We Are Continually Exposed to the Flashbulb of Death” The Photographs of Allen Ginsberg (1953–1996)

February 21–April 5, 2015

Presentation House Gallery

333 Chesterfield Ave, North Vancouver, BC, Canada V7M 2L8

In 1983, Allen Ginsberg had his old negatives re-printed when his archivist and bibliographer, Bill Morgan, discovered them amongst Ginsberg’s Columbia papers. The historical potency of these images was as obvious then as it is now. Encouraged by this assistant and friends like photographers Bernice Abbott, Ginsberg scribed beneath these pictures lengthy captions recalling with sensitivity and detail who and what was in the frame. However, if not for the celebrity of his subjects and by the nature of Ginsberg’s vocation, these annotations largely surpass the photographs themselves through their extraordinariness and bohemian insight. No, Ginsberg’s pictures do not approach the variety of the “art snapshot” that hearken to Gary Winogrand or Nan Goldin, but that is precisely not the point.

Installation view of “We Are Continually Exposed to the Flashbulb of Death” The Photographs of Allen Ginsberg (1953–1996). Courtesy of Presentation House Gallery

Presentation House Gallery is exhibiting Ginsberg’s photographs, which date from 1953 to 1996. This photographic history of the Beats is spliced into the three rooms, more or less chronologically. The visitor is guided through this chronology by numbered pushpins that correspond to a typed document of Ginsberg’s captions. The gallery certainly does not come short on tools to contextualize the work. Every room hosts some helpful, explicative timelines and vinyl texts that mark excerpts of his life; his “psychic marriage” to Burroughs, the San Francisco Renaissance, his first car with Peter Orlovsky, the Beat Hotel in Tangier, spiritual sojourns, or visits to R.D Laing’s house. Given these things, the subject matter evokes sheer Modernist romanticism; men, their cigarettes, their poverty, their coterie. Certainly, the earlier pictures imply a blissful tumult, frivolity and fleetingness, but it all can’t help but feel a little dampened by the arena that mediates these subversive movements in the exhibition paradigm. “We Are Continually Exposed to the Flashbulb of Death” is so organized, carrying us through this history that many have heard about but fewer having read much of the literature it produced. There’s a lot of poetry lost in the translation of these images from the back of Ginsberg’s desk drawer to being presented in a gallery, but how else can you curate a love story, wrapped in a history, or as they say, a Renaissance? How am I to critique a romance? I hesitate to make another impressive list of the impressive people.

Still from “Only Lovers Left Alive.” Film, 2013. Dir. Jim Jarmusch.

In Jim Jarmusch’s film, Only Lovers Left Alive, the protagonists are vampires who are secretly upholding the backbone of Western culture using humans, such as Shakespeare, as conduits and creditors of their cultural genius. The male vampire, Adam, and the female vampire, Eve, are playing chess in Adam’s kitchen in a rundown house in Detroit when she asks, “Did you play chess with Byron?” and “and what about Mary [Wollstonecraft]?” To which he replies curtly, “pompous ass” and “delicious” respectively. According to him, encounters with belletrists can be reduced to either pretentious or sexy. Ginsberg was not a vampire, but he did manage to have two lives as a photographer, one as a witness, and another as a self-biographer. It’s a fine distinction, based entirely on the intention of our photographer.

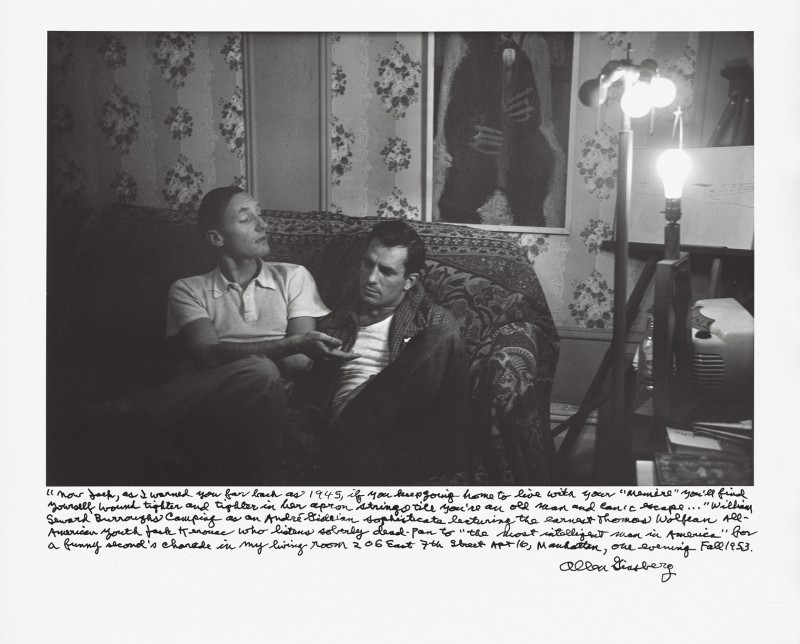

Inscription: “Now Jack as I warned you far back as 1945, if you keep going home to live with your ‘Memère’ you’ll find yourself wound tighter and tighter in her apron strings till you’re an old man and can’t escape…” William Seward Burroughs camping as an André Gide-ian sophisticate lecturing the earnest Thomas Wolfean All-American youth Jack Kerouac who listens soberly dead-pan to “the most intelligent man in America” for a funny second’s charade in my living room 206 East 7th Street Apt 16, Manhattan, one evening Fall 1953, 1953, gelatin silver print, printed 1984–97, 11 1/8 x 17 3/8 in. (28.3 x 44.2 cm), National Gallery of Art, Gift of Gary S. Davis. © 2012 The Allen Ginsberg LLC.

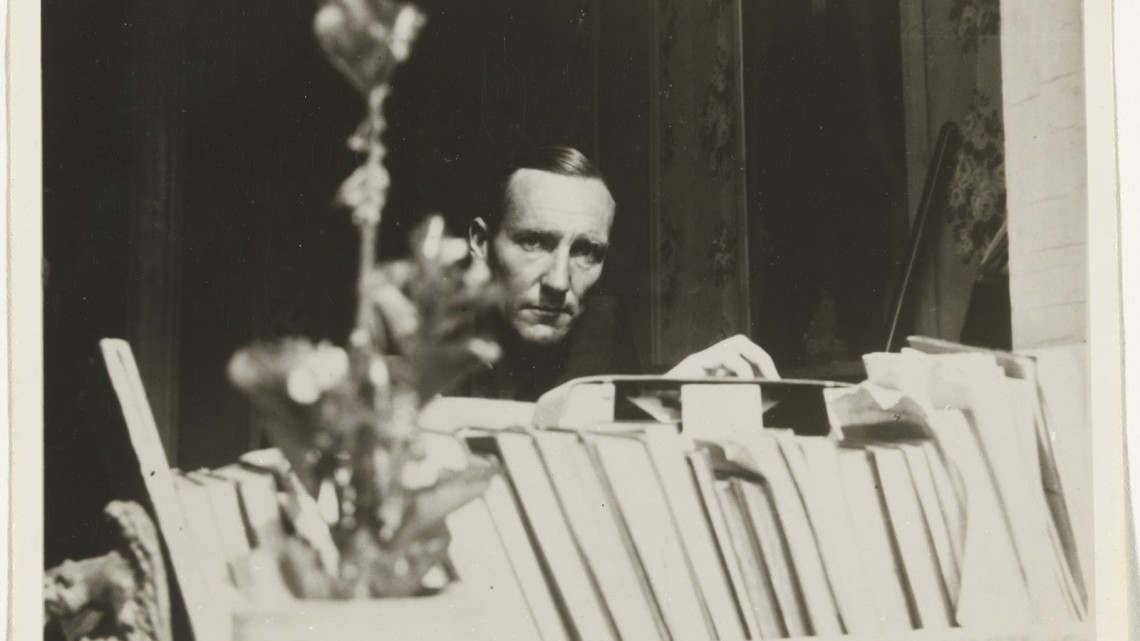

The earliest pictures, and likely the most intimate, were as the poet has said, “meant more for a public in heaven than one here on earth.”[i] This expression is particularly perceptible in the quiet portraits of Burroughs. The white hand of Burroughs motionless atop a thin vague surface and his face floating just above a barrier of books in the unfocused foreground—he looks quite a bit like Baudelaire, actually. Ginsberg saw Burroughs with “a soft center where he felt isolated, alone in the world.”[ii] Whether you are the photographer in a relationship or in a relationship with a photographer, there is always a tacitly formed agreement that intimacy is a photo-op:

“William Burroughs sitting up in back bedroom waiting for my company, we slept together & worked on Yage Letters and Queer manuscripts, Ace Books’d printed first paperback edition of Junky that spring – “I come home from work [on ‘N.Y. World Telegram,’ copyboy] 4:45 and we talk until one AM or later…am all hung up in great psychic marriage with him for the month – “ [letter to Neal Cassidy September 4. 1953] Bill arrived from South America in August and we stayed together in my apartment till December, he left for Tanger, I hitched to Palm Beach, Xmas with his parents, then went on via Mexico to Bay Area San Francisco. 206 East 7th Street Apt 16, Fall 1953.”

Indeed, intimacy is very photogenic, but rarely does it go much beyond that for posterity. With a portrait of Burroughs this vulnerable, the inscription would have been sufficient after “company” or “spring” or the first “1953”. However, with us in mind, Ginsberg supplemented, in one textual breath, the amorous (“we slept together”), the intellectual (“worked on Yage Letters…”), the routine, (“I come home from work…”) the romantic (and we talk until one AM or later…”) the junkets (arrived from South America in August…December…Tanger…Palm Beach…Mexico) the quotidian (“Xmas with his parents”), and San Francisco—which is in the other room with Tanger—and concluded with the address, season and year of the photograph, as if after a novelesque recounting, a nostalgic spiral to be sure, Ginsberg remembered that he should include some indexical information, again for posterity. Certain lines, such as that of a copyboy Ginsberg racing home everyday for three months to talk to the “most intelligent man in America”[iii], images itself in the proverbial lover’s imagination, that important alignment to the equal dedication to talk and sex. Perhaps we are predisposed to seek out the ordinariness in love between literary giants. In regards to that portrait of a semi-nude Burroughs relaxed on a bed, we need not seek any further than just beyond the bottom of the frame.

Warren Beatty and Madonna at Francesco Clemente’s NYE party in 1990; © Allen Ginsberg LLC, 2014.

When his negatives resurfaced from his archives in 1983, Ginsberg was again taken with the medium and began to reach for his camera as often as he would reach for his notebook. However, the thrushes of blur that marked his photographs with the amateurism and spontaneity that dominated his early life is noticeably reduced. Their presence in the latter set resonate as nostalgic, or merely an idiom of his early days—imposed noir. He had sought photographic advice from Robert Frank, and yes, his photographs do get “better” by certain standards, but the majority of the photographs of the more remarkably famous subjects, such as Madonna, Lou Reed and a young awkward Beck, are so unexceptional that they could have easily stayed at the back of his desk drawer with no impairment to the rest of the exhibition at all. The fact that they are located a vitrine is a testament to their peripheral significance. But try, if you can, to look at these portraits, not for who they are, but in relation to the writing beneath them, perhaps the appeal of photo-blog phenomenon Humans of New York will become very apparent. Of course, humans, as they are seen through the lens of the camera, have a magnified elegance foisted upon them…but it is the photographer, in this case, Brandon Stanton, who posts beneath a fairly standard portrait of a woman in the subway, “I’m writing a book that encourages people to cross dress.”

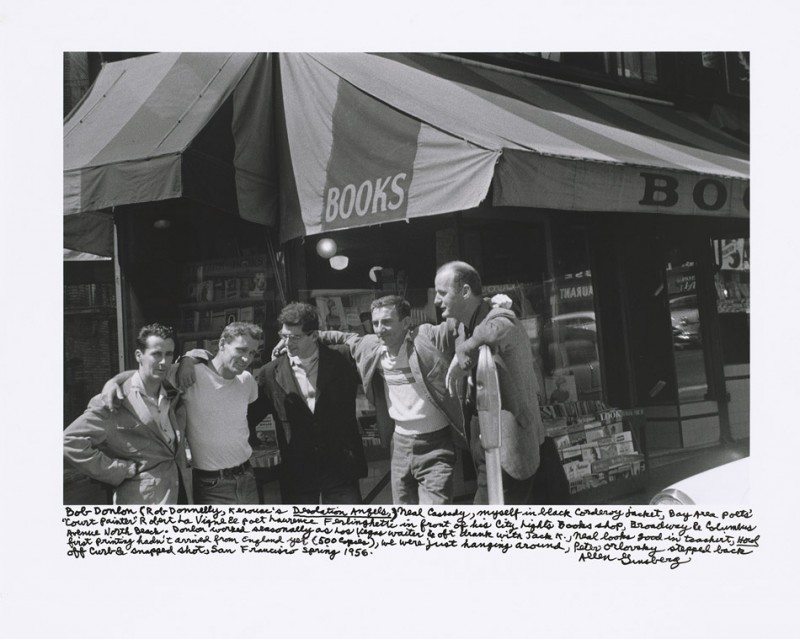

Bob Donlon (Rob Donnelly, Kerouac’s Desolation Angels), Neal Cassady, myself in black corduroy jacket, Bay Area poets’ “Court Painter” Robert La Vigne & poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti in front of his City Lights Books shop, Broadway & Columbus Avenue North Beach. Donlon worked seasonally as Las Vegas waiter & oft drank with Jack K., Neal looks good in tee shirt, Howl first printing hadn’t arrived from England yet (500 copies), we were just hanging around, Peter Orlovsky stepped back off curb & snapped shot, San Francisco spring 1956.

The simplicity of Ginsberg’s annotations suit the content of the early photos, the domestic setting and playfulness of young men in awe of each other finding words for their desires and spirituality. In the later pictures, after 1983, when Ginsberg captured the photos with the task of writing captions later on in mind, the magic of recollection seems dampened too. Though without the discovery of his early negatives, no caption would have been wrote, no photographs would have been printed at all. Ginsberg’s handwritten annotations wavering beneath the black and white images are what keep Ginsberg’s photographs from being reduced to glorified family portraits, and his monographs from glossy photo albums. These captions function almost as essentially as who is in the photographs themselves in illuminating the Beat history, allowing them to function less like historical documents and more like personal vestiges.

“Un coin de table (By the Table)” 1872. Oil on canvas, 160 x 225 cm © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski. Three are standing, from left to right: Elzéar Bonnier, Emile Blémont and Jean Aicard. Five are seated: Paul Verlaine and Arthur Rimbaud, Léon Valade, Ernest d’Hervilly and Camille Pelletan.

While writing the annotations, Ginsberg had asked himself, “What would I want to know if I were looking at a photograph of Verlaine and Rimbaud together?” Letters and history inform us that Paul Verlaine and Arthur Rimbaud was a tragic, uncompromising, landmark pairing in literary fin de siècle, which ended when the intoxicated former shot the latter in the hand. Their union was dramatic and compelling in these terms, but while looking at Henri Fantin-Latour’s By The Table (1872), a group portrait of the Parnassus Poetry Group, the artist divulges nothing more than the suggestion of their proximity in the composition. Rimbaud props his chin on his hand and looks in the direction of his mentor-lover Verlaine, coquettishly, ambiguously, but that’s about it—leaving it all up to Ginsberg’s imagination. Recently, I was able to visit Fantin-Latour’s totally ineffable Portrait of Miss Edith Crowe (1874) at the Hammer Museum. In the didactic panel the artist is quoted as having once said, “One paints people like flowers in a vase, happy just to depict the exterior as it is—but what of the inner life? The soul is like music playing behind the veil of flesh; one cannot paint it, but one can make it heard…or at least try, to show that you have thought of it.” While this painter sits with his subject for an indeterminate amount of time all in an attempt to make a soul heard, or to make evident the attempt, the poet-photographer is issued two cracks at it, the first with only a fraction of a second, and another with a ballpoint pen.

—-

[i] Sarah Greenough “Seeing with the Eyes of the Angeles: Photographs of Allen Ginsberg” in Beat Memories. Washington National Gallery of Art, 2010. 4

[ii] Ibid 40

[iii] This is how Ginsberg refers to Burroughs in the annotation of a separate photograph: “Now Jack as I warned you far back as 1945, if you keep going home to live with your ‘Memère’ you’ll find yourself wound tighter and tighter in her apron strings till you’re an old man and can’t escape…” William Seward Burroughs camping as an André Gideian sophisticate lecturing the earnest Thomas Wolfean All-American youth Jack Kerouac who listens soberly dead-pan to “the most intelligent man in America” for a funny second’s charade in my living room 206 East 7th Street Apt 16, Manhattan, one evening Fall 1953” It is likely that Ginsberg quoted “most intelligent man in America” from a book blurb or review of Burroughs’s work.