By the time any of you are reading this, I will have already given my eulogy for Richard Berger, and only time will tell if it accorded with what I am writing here. Richard passed away on March 3 of this year, after a long battle with several different types of cancer. He was 70 years too young at that time, although not so young as Susan O’Malley or Rex Ray, two other lights of the Bay Area art scene who died at much younger ages, a week and a month prior, respectively. Now was he as old as legendary gallerist Paule Anglim, who passed away at the age of ageless on April 2. There are many others who knew Susan, Rex, and Paule far better than I, so it will be they who will speak the right memorializing words at the right time about those passings. There are far fewer people in the northern California art world who knew Richard better than I, although several people not of that community (including his brother Paul and sister Kathryn) knew him much better. Suffice to say here that we have lost too many too quickly, and these losses are deeply and widely felt.

I have known Richard for four full decades, having met him for the first time in the spring of 1975. At that time, I was a first-semester transfer student at SFAI, and when the spring weather permitted, I would have my lunch outside of the school’s café, where many of us would sit in close proximity to where Richard would trade barbs with another longtime faculty member named Sam Tchakalian (who died in 2004). Their lunchtime repartee was executed in high-speed hilarity with no holds barred, and the range of subjects that they covered was vast and frequently more than a little bit ribald. In some ways, the contrast between them was extreme: Sam was old school old school, a barking, snarling, and fowl-mouthed relic of the time when abstract expressionism ruled the world. Even though Sam was of small stature, nothing interfered with the largeness and loudness of his personality, or its impact on students. In contrast, Richard was loquaciously prolix, meaning among other things that he was a gifted storyteller who knew how to spice his elaborations with layers of wicked irony that were every bit the equal of anything penned by Ambrose Bierce. Richard also had a rare gift couching his remarks in perfectly chosen words that were always made even better by his ability to juxtapose those words in perfectly uncanny arrangements. With minimal verbal effort, he could capture the essence of any object or situation, and his sense of humor was nothing short of astounding. I would not hesitate to say that Richard was the funniest person that I have ever met.

He was also six and a half feet tall, and next to Sam, he looked even taller. And so their repartee would go something like this: Richard would spin a yarn about some less-then-prescient character that he knew from his outlaw biker past, and then Sam would embellish upon it with foul adjectives, to which Richard would then initiate a game of one-upmanship, the moves of which were designed to smoke out those in the audience who were sharp enough to see the multiple levels of humor that were brought into play. Sam was equally eager to show that he was not interested in being left behind by these embellishments, so he in turn would turn up the temperature of his own contributions, looking for moments when abrupt changes of topic could garner the maximum amounts of shock and surprise. And on and on it went, rematch after rematch. I can happily confess here that the mental notes that I kept of these verbal duels have on multiple occasions been repurposed into my own writing, for good or for ill.

At that time, Sam was 46 years old and Richard was 30. He had been already been teaching at SFAI for five years. Prior to that, he had a colorful past in the Sacramento and Davis area, having attended what was then called Sacramento State College before it was renamed California State University at Sacramento in 1972. While he was in school, he was socially connected to some of the teachers and students who were active in the art department at UC Davis, including Robert Arneson and Bruce Nauman. He had cheated death twice, but not without serious permanent injury. The first of these cheatings was when he was a 13 years old living with his family in the San Fernando Valley. Two airplanes collided and exploded in the air above the athletic field of Pacoima Jr. High, showering him (and others) with burning wreckage and leaving much of Richard’s body covered with third-degree burns. Seven of his classmates were killed in the incident, while dozens of others were seriously injured. The second time was in 1969, in a severe motorcycle accident that forced the amputation of his left leg below the knee.

Richard Berger, The fire that stirs about her when she stirs, 1994.

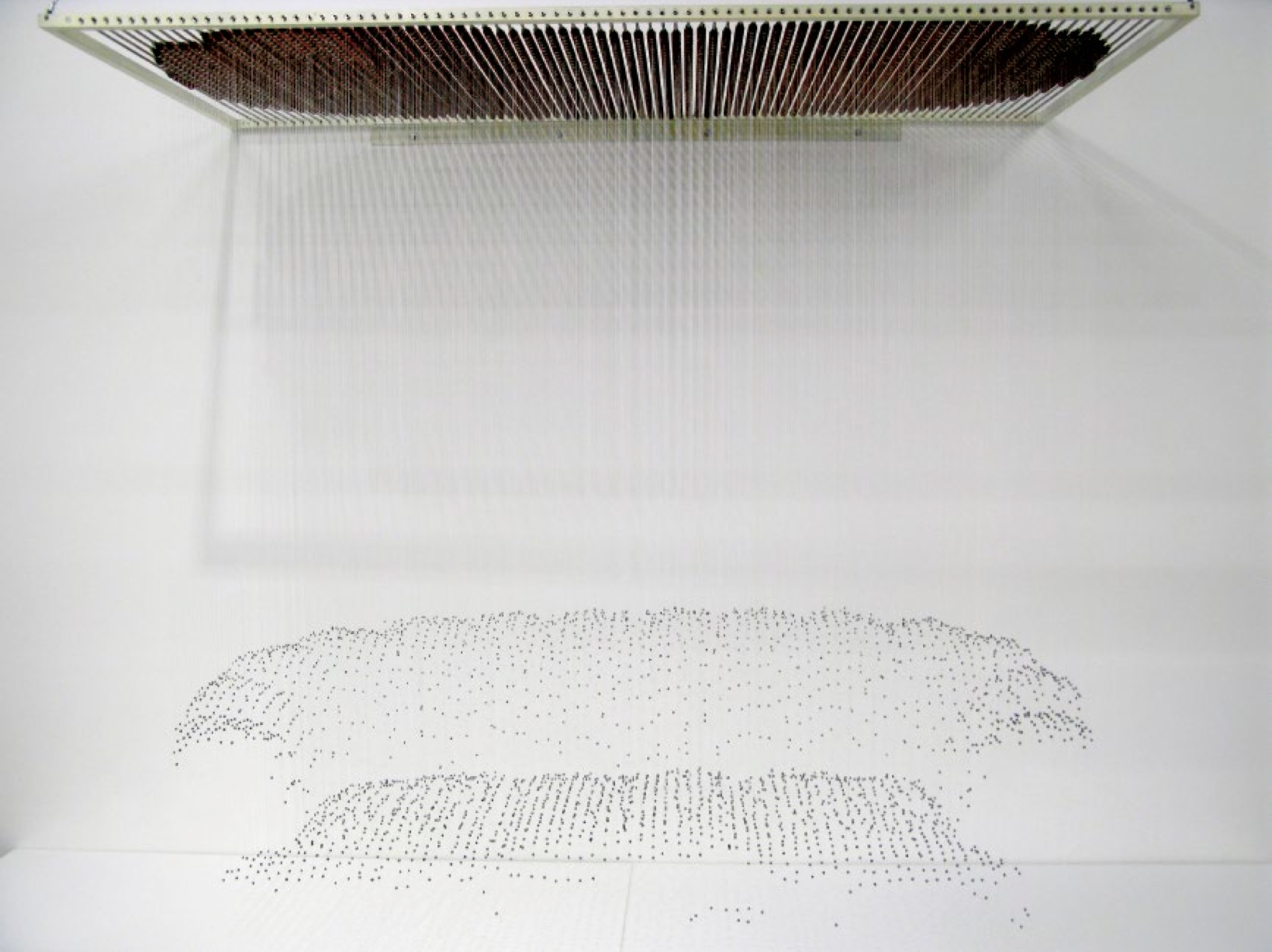

This incident and its aftermath of prolonged rehabilitation exerted a deep effect on Richard’s artistic practice. Long before three-dimensional modeling software allowed for the use of Cartesian geometry for precise plotting of virtual forms in virtual space, Richard had worked out his own wireframe modeling process using materials like aluminum mesh and monofilament. He devised a system of establishing visual form by plotting sequences of anchor points along arcs that would describe the sectionalized layers of the object’s surface. When dozens of these would be aligned in calibrated order, the anchor points would approximate the topography of the object that had otherwise disappeared.

The most well known example is his 1975–1976 piece titled My Couch, in which the topography of the eponymous object was described with lead fishing weights dangling at precise increments. Aside from the stunning way that this work captured the light of the room that enclosed it, it also registered as an uncanny visualization of how the mass of an object could be removed from its volume— an early prophesy of what Arthur Kroker would later call “the will to virtuality.” Like many of the works that would follow, My Couch was an exercise in phantom-object syndrome (read: phantom-reality syndrome) that was born of Richard’s own intimate experience with phantom-limb syndrome—that being the sensation of still “feeling” a limb even though it has been lost. By using this sensation as a point of departure, Richard’s work extrapolated whole worlds of objects designed to contain the ghosts of their own previous states of having been fully embodied.

Richard Berger, My Couch, 1976.

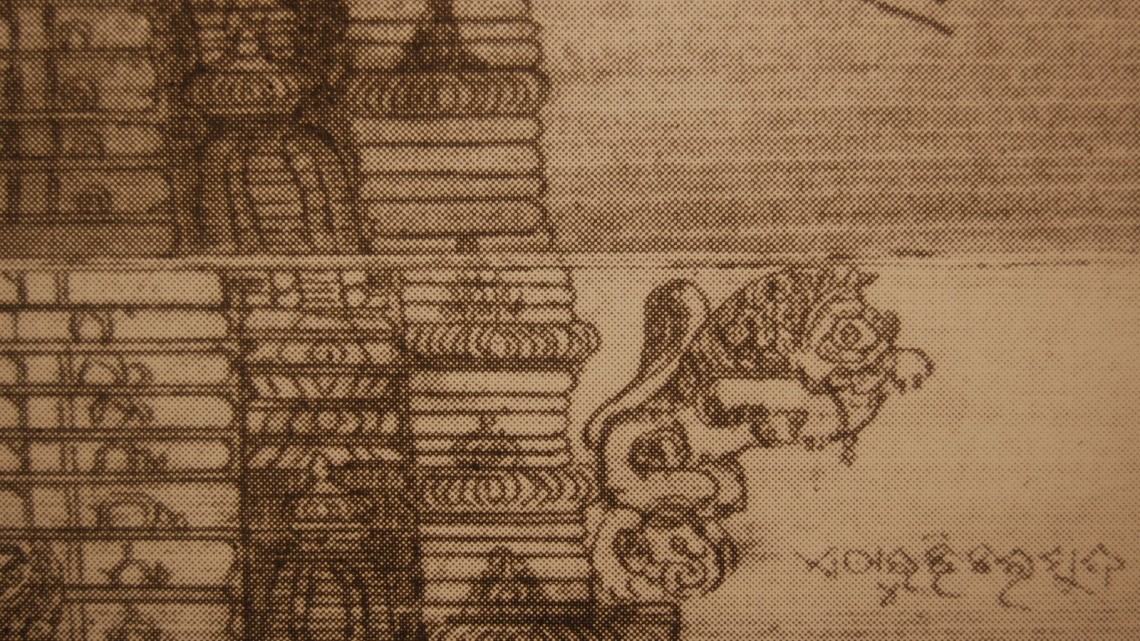

Richard’s most recent work was a precisely scaled model of the 13th century Sun Temple at Konark located near Jagannath in the Indian province of Orissa. Richard had visited the temple twice between 2004 and 2008. He had also conducted a thorough study of its history, as well as its physical and symbolic structure. He called this work The Prosthetic Temple (2008–2010), and it was exhibited twice in recent years, once at the Meridian Gallery in 2011 and again at the Canessa Gallery in 2012. Several years in the making, The Prosthetic Temple was not only the culmination point of his work but also the most complete material embodiment of his theory of the purpose and definition of art. In his own words, “I propose that one attribute of the production of those makers we call artists, historically and culturally, constitutes a kind of prosthetic activity to address an unforgettable and irreconcilable absence. To forget would be to surrender to incompleteness, an untenable and intolerable state. This production, the work of the artist, is intended to, however imperfectly, reestablish completeness. This leads to the consideration of cultural, psychic, intellectual, and/or spiritual categories of the prosthetic construct.”

Richard Berger, The Prosthetic Temple, 2008-2011. Redwood, 48 x 60 x 81 inches.

Even though Richard was generous to a fault with his students, he never suffered fools gladly—a fact that was never lost on his colleagues at SFAI. Indeed, he could be outright salty when the occasion called for being so, and the wasting of time for no good reason was especially irksome to him. One example of this kind of saltiness that I remember took place in the late 1980s. He and I were drinking coffee inside the SFAI café waiting for the start of our afternoon classes during the first week of a spring semester. A shy student walked up to him and said, “Professor Berger, excuse me, but I think you gave me the wrong grade for the class last fall.” Richard looked up at the student and calmly said, “Yes, I probably did give you the wrong grade, but an F is the lowest grade the school would let me give.” As it turned out the petitioning student had failed to attend most of the meetings of the class in question, and Richard’s cutting short of that rather feeble attempt at emotional blackmail was only natural. Up until about 2001, he refused to attend the openings of his own exhibitions, on the grounds that he found it exasperating to “be the straight man at everybody else’s cruise scene.” During those years, when called upon to do slide lectures about his own work, he would often sit with his back to the audience and remark directly to the projected images, letting the audience eavesdrop on his internal monolog.

Add to all of this the fact that he was an amateur art historian of the highest order who taught an annual class in the history of sculpture for most of his 45 years at SFAI. That class is now the stuff of legend for the students who took it, and that reminds us that the term “amateur” literally means one who does something out of the sheer love of it. This encapsulates the way that Richard conducted his classes, his artistic practice, his many hobbies, and all of the many other aspects of his rich and adventurous life.

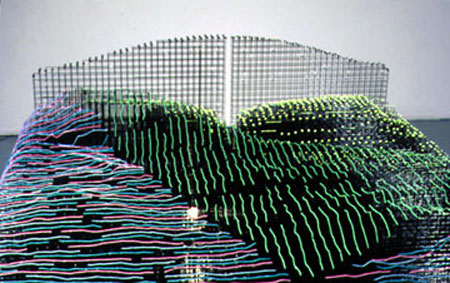

Richard Berger, Constellation, 1983.

Richard Berger, Constellation, 1983.