What if the technology from Google Street View was used for more than superficial spying? What if the code-writing idealists among us turned their sights away from virtual tours of well-marketed real estate and toward more democratic notions of space? The ability to observe unknown locales is the inception of contemporary access, catalyzed by the Internet and digital media. When that ability for observation is put to academic use via the vision of Portland-based makers, the consequences have unforeseen affects on the space for art production.

1995 gave the world its first spherical video camera courtesy immersive media mastermind David McCutchen. Now known as the Dodeca 2360, a beta version was constructed as a compact 11-lens device capable of recording images from multiple angles simultaneously. The resulting integrated streaming, combined with four-channel sound, is an act of geometric wizardry. Fast forward 10 years, and the summer of 2015 sees the release of this innovation put to landmark use. It’s an app called “8” and due to its innocuous name, is hardly even searchable online. For forward thinking contemporary art lovers, however, it’s worth the dig. Artist and Pacific Northwest College of Art (PNCA) professor Stephen Slappe (in collaboration with McCutchen and software developer Jacob Fennell) has produced what may possibly be a coming of age for artists and curators working in new media or toying with the democratization of exhibition space: he filmed a complex, time-lapsed video and released it as an application.

Stephen Slappe. Publicity icon for 8 the app, 2015.

Filmed in the 511 Federal Building that now houses PNCA, 8 allows users (or “exhibition visitors”) to guide themselves through a maze of non-linear information and a world of cloaked optimism about alternate futures. The building has an interesting history: prior to an intensive remodeling over the past year, 511 NW Broadway housed a number of government agencies from the Department of Homeland Security to Immigration Services. Even now, the architecture and ornamentation still bares many of these markers. Slappe and collaborators seized the rare opportunity to film in the building during the days leading up to PNCA’s takeover. The basement, barren of all its former office wares and ominous documents of surveillance, was left eerily desolate. Leftover signage and demolition graffiti is present in many cuts of the film’s footage. Users can follow these strange (in some instances, glowing) markers through several flights of stairs and floors. It is Slappe’s conception that, as with exhibitions in physical space, one gets as much experience as they seek. As you move through real time and space with your smart-object of choice, cellphones and tablets being favored, your unseen avatar navigates virtual space and the artist’s pre-recorded loops of theater. This is another reason 8 is special: it takes a finely premeditated act of choreography to have the same experience twice. Slappe intentionally conceived that 8 “deal in perishable material—human minds.”[1] The appearance and disappearance of navigable symbols is ephemeral and motion-dependent.

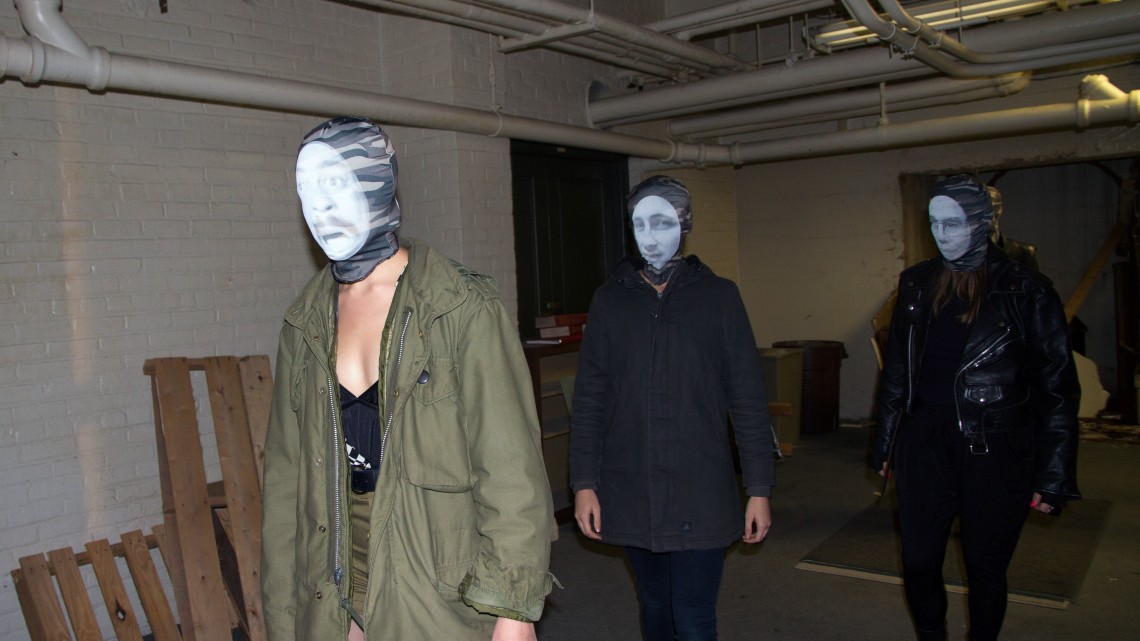

Stephen Slappe. Documentation from the filming of 8. Pacific Northwest College of Art, 2015. Photo credit: Sarah Meadows.

On the surface it seems simple: the Internet grants larger audiences than traditionally attainable. But in reality, 8 took a great deal of mental gymnastics to rationalize in the age of ubiquitous publicness. What does it mean to put art on the web? How do we differentiate the community-enhancing content from the clutter? Conceptually speaking, can the presence of each be valuable—and who decides which is which? It is within the Marshall McLuhan adage, “the medium is the message,” where many art practitioners find their answer. 8 as an artwork is indivisible from its mode of transmission. Its narrative is married to a nondiscriminatory platform. What Slappe has created is interactive with political aims.

If one’s own curiosity doesn’t facilitate exploration, then the experiment is over. 8 yields only to the bodily generosity it is first given. Its ghostly characters and environment are apparitions of not only spatial potential, but also the working definitions of space that once were.

Stephen Slappe. Documentation from the filming of 8. Pacific Northwest College of Art, 2015. Photo credit: Sarah Meadows.

Previously, the public life of an artist’s project was confined to the narrow conception of the exhibition as a curated gallery space. However, the 1960s birthed an evolution in both thought and practice that proved integral to current, expanded notions of what an exhibition might be. Books, magazines, catalogues, and printed matter, which were traditionally used as context-building material for exhibitions, were allowed consideration as viable exhibition spaces of their own. As artists like Joseph Kosuth and Lawrence Weiner increasingly experimented in dematerialization as the nature of their work, the methods for their display were forced to follow. To accommodate this propelled thinking, Slappe has used the Internet and downloadable app culture (in a manner parallel to the use of printed matter years prior) as an exhibition vehicle. When the forms of public presentation are democratized through such a laterally accessible platform, the art audience is at least expanded across class and educational barriers—if only still combatting economic ones.

Stephen Slappe. Documentation from the filming of 8. Pacific Northwest College of Art, 2015. Photo credit: Sarah Meadows.

Interestingly, 8 has also been produced with an accompanying booklet that elaborates (however poetically) on the futuristic world Slappe has created. This gesture is another instance that demonstrates the artist’s penchant for history and his gamer roots. Likewise, iconic titles like Doom and The Legend of Zelda have also seen fit to produce supplemental context for the imaginary worlds their users engage. Zelda’s edition, Hyrule Historia, is a full 276 pages alleviating crowd-sourced speculation about the precise chronology of events that catalyzed the video game’s narrative. 8’s booklet, similarly, clarifies its own internal symbology. In the words of Slappe, “8 is a shadow of the future.”[2] This is a future where numbers do not necessarily represent a value, but a shape. The performances are infinitely variable, and the filming beautifully looped. 8 is revealing in its form: in this future, the human experience will be one of spatial democracy, choice, and upward trajectory. The stairs in the 511 building are presented as a vehicle to somewhere we hope will be better. Upper floors are akin to broader knowledge, or the route to an exit. The gesture of following masked companions through the darkness is one of trust. It signifies our willingness to be a part of what we cannot clearly see, but are somehow physically compelled toward. What Slappe has imagined is the marriage between exhibition and enacted consciousness. 8 is a work metaphorically tied to the past and future—both spheres acknowledging the problem of the white cube and the interaction that will lead us out.

—

[1] Slappe, Stephen. Either Or: A Companion to 8 the app. Social Malpractice Publishing No. 27, February 2015

[2] Ibid.