When did you become or realize you were a conceptual artist?

I think it was probably in the late ‘60s when I wanted to push the boundaries of traditional painting and sculpture. This included incorporating sound, space, light, emotion, and context. Much of the experimental work I was doing in those early days became the armature for future work.

What does being a conceptual artist mean in your terms? What is your definition?

Process rather than finish, perception overriding artifact. The artifacts convert into leftovers that are often ephemeral, temporary, and fragile.

It has been said that a lot of conceptual artists come from sculpture rather than painting or other disciplines. Would you agree with that and, if so, why or why not?

The only training available until the late 1970s or early 1980s was traditional. I think everything evolved eventually and therefore extended from those forms.

In the ‘70s I was experimenting with site-specific work—the context of the work—and used sound and identity to create fictional personas. I made a hotel room in 1972 with the hotel room being the context that people moved through for a period of almost a year.

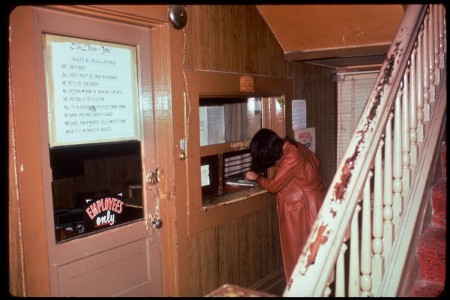

Lynn Hershman Leeson, The Dante Hotel, 1973–76. Courtesy of the artist.

Was that The Dante Hotel?

Yes. The Dante Hotel (1973–76). The ambience of the place and fragmented identity of people who lived there were part of the work. I did a number of projects that grew out from the Dante, including the Roberta Breitmore project, which was a 10-year performance, and the windows of Bonwit Teller. I was also associate project director of Christo’s Running Fence, and started the Floating Museum, which was a museum for artists who used non-traditional methods to create their work. The Floating Museum existed outside the format of traditional museums, because museums in the 1970s wouldn’t even show photographs of artists like Cindy Sherman, Gordon Matta-Clark, Doug Davis, Eleanor Antin, and a number of others. I also did a performance called Lady Luck: A Double Portrait in Las Vegas in 1975 in a casino. In fact, I did several site-specific performances in a number of places including development homes in Australia, San Quentin prison, and even a needlepoint store in San Francisco. Then, in the end of the 1970s, I started my first interactive work, Lorna (1983).

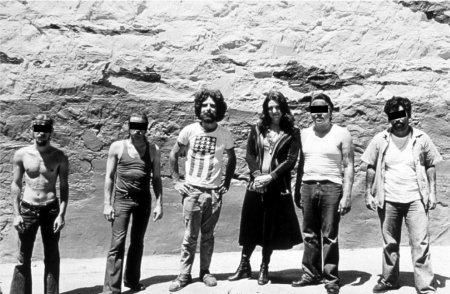

Lynn Hershman Leeson, Hilaire Dufresne, and San Quentin inmates in front of mural produced by The Floating Museum, 1976. Archival digital photograph. Courtesy of the artist.

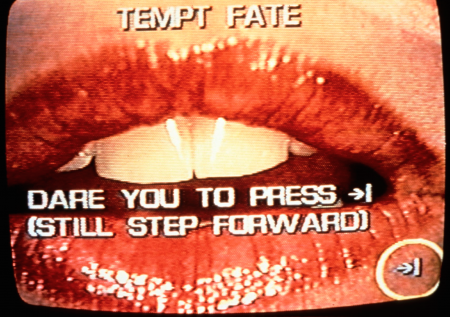

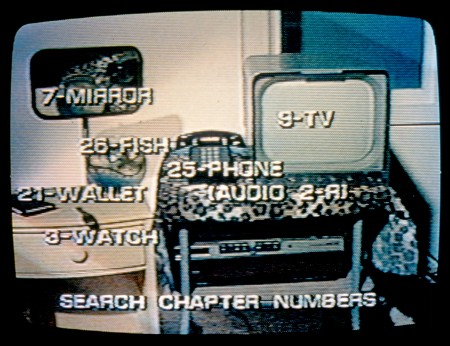

Lynn Hershman Leeson, Lorna, 1983. Interactive videodisk. Dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist.

Can you talk more about Lorna as the first interactive video artwork?

Lorna grew from the hotel rooms and the experience of flowing through that architecture, seeing something from all sides, and then negotiating the possibilities of multiple experiences, like a cubist painting, by incorporating technology.

You did a huge amount that seems to have been related to identity explorations, which was an important part of the art of the 1970s. Can you talk a little bit more about that?

I think women in particular were searching for their own history, and their own identity. In the projects I have done specifically about identity, there were female protagonists like Roberta, or the characters in the Dante Hotel, or the characters in the four hotels (The Chelsea, the Plaza, and the YWCA in New York and Circus Circus in Las Vegas), or Lorna. They’re all females searching for a sense of who they were—of their place, of their time, and of the things that made them real. The feminist movement, which simultaneously started in Chicago, Fresno, and Southern California, revealed how a lot of those artists were also trying to find a place for themselves. There was no available history of women artists. It was all underground. I think that was a big factor for women in the 1970s—we needed to come to terms with who we were, and how we could insert ourselves into history.

I think the artists of your generation did a really good job establishing a canon, and in looking at what younger women are doing now I think that there’s finally a tribute being paid to that period of time. But it has taken a while for the history to be documented properly, or to be documented at all. In terms of the work that you have done since the ‘70s, would you say that there’s been some kind of steady path that you feel you’ve been on in terms of ideas that you were exploring then?

The work takes different forms, but it’s really about the projection of media on women’s identity, and how you define reality and defy marginality. My work has taken the form of interactive photography, of books that deal with the Internet, or performance-based pieces. But it’s all really about how we’re seen, how voyeuristic society has become and how we can become victims of this scopophilic surveillance through ignorance. I’m interested in reshaping perception to help move an individual out of the victim role into one of empowerment.

Have you taken that work out of the context of art and into the world? It seems like it has tremendous social implications.

Just in my films, which have been independent so far and so they have kind of a limited audience, but a bigger audience than only the art audience.

Can you talk more about your own identity exploration? What was it about the 1970s that prompted such an exploration for you?

After completing The Dante Hotel work, I assumed and constructed identities based on the context of that particular location. Items were placed in the rooms and became sociological evidence of their lives, economic realities, and statuses. That evolved into liberating an invisible identity, Roberta Breitmore. Roberta was a fictional identity who would interact with real life by placing ads in newspapers, by answering the ads, and by having various adventures for almost 10 years, each one growing out of the other and building her reality through these real interactions over time. She would see a psychiatrist, she would have her own handwriting, she would have checking accounts and credit cards, a driver’s license, and all the things that identify you in society as real and also create a history where you can track that person. I mean, if you went back to the 1970s Roberta would be more real than me because I couldn’t get credit cards. There would be a track record of her that was more substantial than mine.

How was that for you? Did you have feelings about living with this alter ego?

For me she was objectified. I saw her as an entity in the tradition of Antonin Artaud, of living theater, of sculpture. But nobody else understood that and they thought I was schizophrenic and doing this weird thing. Nevertheless, I was holding on to my belief in the importance of this project, the complexity of it, and its relevance in time as a kind of tracking. I just do things. My projects are usually rejected at the point of time when I do them and criticized or made invisible—which is the same thing—until many years later.

Perhaps it’s part of being an innovator; perhaps you’ve just been ahead of your time consistently.

People do say that. Ellie Coppola says, “When you’re pushing the edge, you know it gets lonely and it’s tough because you’re out there pushing that, but that just seems to be my fate. I see things clearly and I think everybody else is seeing the same things, but they’re not.” Or the language hasn’t existed to talk about things.

With the interactive works, I remember I had to write the language for people to understand what it was or what we were doing, including the idea of being a user if you were a voyeur. I wrote all those things to send out to explain the work that I was doing during the 1970s. I had to make little booklets to explain each work theoretically, or to put it in a context where people could see what I was trying to do.

People don’t understand totally the ramifications of the work I’m doing, but I figure in time it’ll play out. I’m not doing something for the first weekend’s box office. People will look back and they’ll eventually collect Lorna, which was really a disaster when it was released. People hated it. I just have that as kind of a reference that you have to hold on to your belief of what you’re doing and your belief that you’re right and you need to listen to your intuition. If you don’t, then you’re lost.

Can you talk a little bit more about Lorna? Have attitudes toward this work changed over time?

When Roberta seemed to have a series of difficult adventures in her life, I made her into a multiple because I was afraid I was projecting onto her. With Roberta, the ritual became the symbolic burning of her ashes and rebirth into a new being. That’s when I came up with the idea of Lorna. Lorna lived in a single room in The Dante Hotel, with no contact with the outside world. You’re able to access different elements of Lorna’s life by clicking onto objects in her room. So you could click on the fishbowl, you could click on her bed, on her chair, and they would tell short vignettes that had three alternative endings. There were also two different soundtracks that really used the media in what I thought was a sculptural way. It related to the Dante Hotel project as a kind of walking through rooms, which revealed things.

Lynn Hershman Leeson, Lorna, 1983. Interactive videodisk. Dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist.

There seems to be an intersection of identity and place that occurs with this work. Can you talk about why you came to San Francisco, and whether San Francisco, or being here, has supported you as an artist?

I came first to Berkeley to go to graduate school, but I couldn’t figure out how to register, so I quit. I was married at the time and moved to Los Angeles and came back to San Francisco because my husband at the time got a job here. I don’t think San Francisco has been friendly at all. I think it has really been hard and filled with rejection of my work, and me, and this continues still. For instance, in San Francisco, the last review of one of my art exhibitions was in 1993. Thomas Albright, in fact, said I was “the worst disaster to ever hit California!” Kenneth Baker said he had nothing to say about my work. There is an insidious prejudice that I have talked about in !Women Art Revolution. How do you counter it? To me, that kind of invisibility is a kind of murder. It symbolizes the erasure of one’s history. I work in Europe and New York mainly. I’ve had a show every other year in the last 10 years and the works have been bought by major museums including the Museum of Modern Art, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Canada, and by Donald Hess, to name a few. They’ve been written about all over the world, except in the Bay Area.

It seems impossible to believe that you would be left out of any history of this area because you’ve done so many important things that have had an influence on the direction art has taken.

I won the Hamptons International Film Festival Sloan Award for writing and directing Teknolust in 2002, a major award given for film directors. I won the Prix Ars Electronica in 1995 for Difference Engine #3, and was the first woman in 20 years to ever win. I also won the Siemens Media Art Prize in 1995, a Lifetime Achievement at ACM Siggraph in 2009, first prize at the Montreal International Festival of Films on Art for !Women Art Revolution in 2012, the Women’s Caucus of the College Art Association’s first Media Award in 2012, so many . . . nobody in San Francisco would publish that I won these awards.

It’s an interesting contradiction to your career and your profile because you want your hometown to acknowledge you and at the same time there’s an irony in the fact that you’re being acknowledged in larger markets around the world. With that in mind, why didn’t you go to New York?

I was a single mother for a while, so I didn’t have the resources to move with a child.

It also seems that your work during the ‘70s was about the place you were living, which was San Francisco.

I think that the idea of context and site-specific work certainly stems from that time, and it was a political era, just after the Free Speech Movement in Berkeley during the 1960s. In 1968 in Europe, my work was about empowerment of an individual and understanding the context of the site and all the ramifications that place has.

Can you talk a little bit about the scene in San Francisco during that period?

I always felt that I was an outsider. But the fact that I was a struggling single mother made me self-directed in particular ways. I also think that other artists involved in the performance art world at the time didn’t really understand what I did or consider what I was doing as art.

Even though a lot of what they were doing had tremendous affinity with your work?

It was a club. And I still have never been invited to one of Tom Marioni’s beer parties. So I didn’t really have much of an interaction with other artists in that group. Women weren’t considered artists in the 1960s and ‘70s, plain and simple.

Little did they know!

Hopefully they found out!

Was there anything about the politics of the 1970s that influenced your work?

I think it was the idea of autonomy. When I was at Berkeley, and all the uprising was happening, the idea erupted that an individual could change something, and that you didn’t need institutions. Without that structure invading my thinking I would not have gone into The Dante Hotel. I thought I could take on the world. And the thinking of the time was that an individual could really make a difference. Once again, you have that personal empowerment that was so idealistic. It permeated.

Who do you feel influenced you, your work?

Marcel Duchamp, and meeting Arturo Schwarz and learning from him. I like to also say Cézanne for the idea of looking around things. For me, it’s any artist who really has shown courage in their work, who has not gone the traditional way. Artists I admire are the ones who have taken their own risks and beliefs, and pushed them to an edge, and did it despite the odds and despite the consequences, just because they felt that they had something that was so important that they went towards it.

I’m fascinated by what you said about Cézanne—his way of looking around things. Do you mean the way in which he used multiple perspectives?

Yes. We can’t separate our own history. At the end of the third grade, I was separated from my class and sent to college. I think that that kind of displacement, of being the odd person, enabled me to peer at situations from the outside, like a witness. And I think that was kind of a profound experience, as was being in Berkeley during the Free Speech Movement, feeling that it was kind of a parallel for your family dynamics growing up; elements that you deal with in order to individuate.

Did you ever write a manifesto?

I wrote a manifesto of every piece I did!

Do you still?

I do. They’re shorter, but I still write something every time, kind of basing it in history and practice.

It would be interesting to hear you talk more about the continuity of your work between the 1970s and now; the development and direction you’ve taken.

I really think that it’s pretty much the same. I think especially Teknolust (2002) relates very much to Roberta. Teknolust is about a biogeneticist who creates three clones of herself— Olive, Marine, and Ruby. This biogeneticist was called Rosetta Stone. I made three Robertas, and the three Robertas went out in the world as multiples, trying to individuate, just like these three, who go out and escape and try to grow and have experiences. The difference with Teknolust is that they have happy endings. Roberta’s character has a tragic ending. There is an exorcism with all the negativity: her purse getting snatched, all the things that were happening to her. The latter characters, Olive, Marine, and Ruby, fall in love or find fulfillment, find art, find love, find beauty in the world. I think that that kind of difficult angst of the 1970s has shifted to having a strong sense of humor and resolution.

Still from Teknolust, 2002. Feature film, 24p high-definition video, 83 minutes. Courtesy of the artist.

It seems that it must somehow also reflect your changing experience between the 1970s and now.

Yes. The 1970s were pretty tough for me. I think Howard Fox has called it redemption! I think my work now is much more mature and resolved. And it is finally being seen, after 50 years, in my retrospective currently up at the ZKM in Karlsruhe, Germany, and also at Bridget Donahue Gallery in New York. Rudolf Frieling recently included me in two shows at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and Paule Anglim Gallery will show some older, as yet unseen, pieces at the Frieze show in May. In 2011 the Museum of Modern Art, New York acquired 42 of my works for their permanent collection, and during the summer of 2015, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art will determine whether or not to add several of my works to their permanent collection. It is quite gratifying to see these works finally appreciated. I feel like I’ve come into the arc, and will be floating with much less chaos into the arc of history and time.