This interview has been pulled from SFAQ Print Issue 16.

Marian Goodman founded Multiples in 1965, publisher of limited edition artists’ prints, objects and books. She opened her 57th Street gallery in 1977 (in its present location since 1981) with a strong commitment to European artists. It remains one of the most respected galleries in New York.

I know that you grew up in Manhattan and that your father was an art lover whose passion obviously set you on your path.

My father was a very unusual collector. I am not sure he had great sums of money to spend, but he was an avid reader and museumgoer, especially focused on the painting and sculpture of the 19th to mid-20th centuries and enthusiast of art history, especially. It isn’t that he collected widely, but he fell in love with the work of one artist in particular, Milton Avery, and he just seemed to have a deep joy in collecting his work. They became friends and saw each other on a regular basis. My father did have relationships with some other artists from whom he would buy work, but his real love was Avery.

So, you knew Avery?

Yes, he was a lovely man, and I still love his work. He was a wonderful man. I think he was a great colorist and it is generally acknowledged that he had a substantial influence on Mark Rothko in that regard.

You must have had many Avery’s in your apartment.

Yes [laughter], in my family’s apartment; floor to ceiling.

And didn’t an Avery painting have a part in your starting a gallery?

Yes, my father gave me an Avery painting that was worth $5,000, and I sold it to help launch Multiples with the idea of publishing limited edition artists’ prints and objects.

I read that you started Multiples in the mid-sixties after approaching the Museum of Modern Art [MOMA].

Yes, the idea was to make works by the most respected artists and best craftsmen available to the public at affordable prices. They weren’t interested, so I did it on my own with some partners.

When did it close?

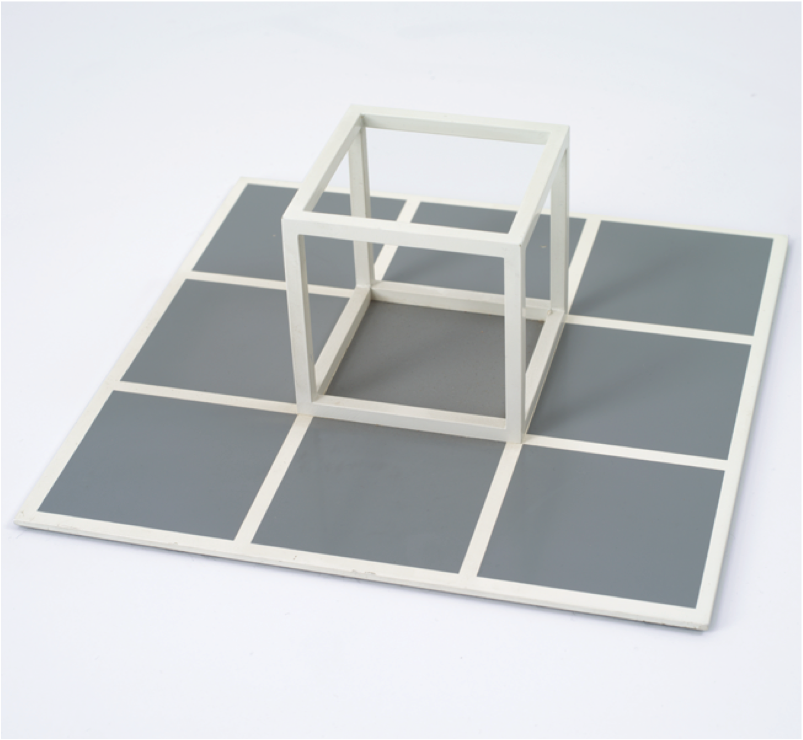

In a way it never closed. Once I started the gallery in 1977 it became clear that I couldn’t do two things at once, and I wasn’t interested in many of the artists of the 80s, so it was easy for me to slow down. However, I continued to do projects with artists whenever the right moment came, but no longer actively, just selectively. For example, at that time, I published most of Sol LeWitt’s editions and all of [Claes] Oldenburg’s etchings and aquatints.

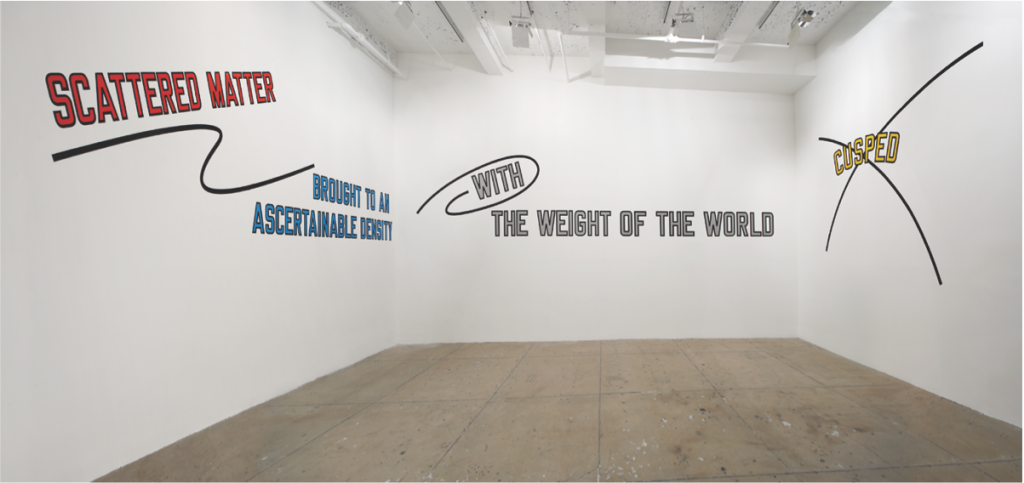

Lawrence Weiner, “SC ATTERED MATTER BROUGHT TO A KNOWN DENSITY, WITH THE WEIGHT OF THE WORLD, CUSPED,” 2007. Language + Materials Referred To. Courtesy of Marian Goodman Gallery, New York / Paris.

You were one of the first dealers to recognize European artists.

It was a strange thing about the States. There was a whole world of very exciting European artists, but the news didn’t come here, or only sporadically. There were exciting artists working in Italy, the Arte Povera group, for example, that hardly anyone knew. A few—Richard Long and Jan Dibbets—were showing with Leo Castelli or John Weber’s gallery, via his Italian wife Annina Nosei. But in general European artists had no presence here.

What got you interested in the Europeans?

My field of study was modern European history, so I had some familiarity with European cultures. It wasn’t a mysterious place to me. Also, one of my colleagues who was close to me and the Multiples gallery, a young German man who was our graphic designer, encouraged me to learn about contemporary European art. I was curious before then, but I never wanted to go to Germany given the history of World War II. In the process of knowing him, I began to sort things out and realized there was a generation of artists born after the end of World War II who could not be fairly held responsible for what took place before their birth and were very aware of their past and wanted to make amends. In retrospect, I realize how dedicated they were in seeking out better models. Through that friendship I went to Documenta in 1968 for the first time where I saw work of Joseph Beuys. When I returned to NewYork I tried to persuade someone at MoMA to show a wonderful film of Beuys’s, which I felt was very moving indeed. Beuys was influenced by Samuel Beckett. In one of Beckett’s novels the lead character transfers stones from his left to his right trouser pocket, seemingly unable to decide where they should remain—an existential dilemma. And in his film, Beuys echoes the dilemma, moving a gigantic pile of wood from here to there, looks at it, and moves it back and forth again, or to a third place, and back again—another existential dilemma. I thought it was wonderful and tried to get MoMA interested but they weren’t.

Sol LeWitt, “Untitled,”1975. Metal construction, 10 x 10 x 3.75 inches. Courtesy of Marian Goodman Gallery, New York / Paris.

Again!

After that I began to publish Beuys and the British artist Richard Hamilton. I was very eager to meet Marcel Broodthaers who was a friend of Richard’s. He said, “come to Berlin, there is going to be a Fluxus meeting, and I will introduce you to Broodthaers,” and that changed everything for me. I began to publish with Broodthaers and tried unsuccessfully to get him a gallery in New York. Since no one was interested, I decided that I would try to show his work myself. That’s how I started a gallery, completely impractically, and with dreams.

Your first show was Broodthaers?

Yes, two-thirds Broodthaers and one-third James Lee Byars.

Even now the majority of artists in your gallery are not American.

But I do have several—Dan Graham, Lawrence Weiner, John Baldessari, and now Julie Mehretu. When I published editions, I worked with a number of the Pop artists, especially Rosenquist and Oldenburg, and many others like Artschwager and LeWitt. The gallery has grown like topsy since then; one thing led to another, as it does in life.

I know you travel extensively.

Yes.

And in your travels you see new artists. Is that the primary way in which you discover artists?

I see a great many shows, but sometimes artists come to me and sometimes artists in the gallery recommend other artists. So, there always seems to be a flow of artists to consider.

Your current show of William Kentridge is based on work that was in Documenta last year.

Yes, very much so. “The Refusal of Time,” the piece he presented at Documenta, is now at the Metropolitan Museum; it’s very exciting.

Yes, I read that it is co-owned by the Met and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Yes.

Installation view, “Sculpture,” May 5th–28 May, 1983. Richard Artschwager, Claes Oldenburg, Sol LeWitt. Courtesy of Marian Goodman Gallery, New York / Paris.

Did you travel to Moscow to see Baldessari’s recent show there?

You know, I didn’t. It was the craziest month I’ve ever had. There were two other museum shows by gallery artists in two other countries at the same time, and an opening here in the gallery one day after Baldessari’s opening in Moscow. Life seems to double up that way.

You’ve been in this space at 24 West 57th Street for a long time?

Since 1981, and from 1977 in another 57th Street location.

You’ve expanded the gallery, but you never followed the exodus of 57th Street galleries to SoHo, nor did you move to Chelsea, why?

A combination of things. Most of the gallery artists liked being uptown, especially the European artists. Also, often the spaces are too big. It didn’t seem like the best way to look at art. It is too distracting for quiet looking. Since more of them felt that way than not, I decided to stay.

Big spaces encourage artists to make art to fill the space and that can lead to overblown work.

There’s a lot of that that goes on.

But you did open a gallery in Paris in 1995, why was that?

It didn’t have to do with making a fortune—Paris isn’t that kind of a market. I represent about fifteen European artists and I try to see them regularly. That means a lot of traveling in Europe, which gets to be challenging, getting from place to place. I always try to end each trip with a weekend or so in Paris, which I love, to catch my breath. I opened the Paris space through a crazy mix of circumstances. I had been asked by a French curator who wanted to start a Kunsthalle in Paris if I would join as a commercial gallery. Some of the artists in my gallery loved the idea. Ultimately it didn’t work because of lack of funding. Then later, I thought to take a pied à terre. I rented a tiny space.

I visited the gallery—it was upstairs, wasn’t it?

Yes, and it was only about twenty feet square. Ultimately, artists became interested in showing there, so no more pied à terre, rather a small gallery. I had to curate the shows because you couldn’t just fit anything in such a small space. When the lease was up after five years, I decided that if I could find the right space where the artists had room enough, I would continue, and so I did. I found a very beautiful space at the last minute of the last hour, making it possible for me to continue.

Richard Tuttle, “The Place in the Window, II,” 2013.Wire, mesh wall sculpture, 17.75 x 21.25 x 5.75 inches. Courtesy of Marian Goodman Gallery, New York / Paris.

I know you had a show of Richard Tuttle’s work in Paris recently.

Yes.

Is one of the reasons to have a gallery elsewhere because you can show artists you don’t represent in New York?

I don’t think it’s a driving force. I’ve only just started to show artists in Paris who I don’t represent. Many of those artists don’t show in Europe, which is strange, and for the most part they are artists that I had worked with when I did publishing, like Tuttle and Sol LeWitt. It wasn’t as if I was running around trying to find new people.

I received an email announcement recently that you are going to open a gallery in London?

Yes, in about a year.

In what part of the city?

It’s in Soho, Golden Square, which is a very nice area. We started by wanting to open a small space. I tried to find one in Mayfair, but I couldn’t. A real estate agent showed me the space we finally settled on, which is flexible and it promises to be beautiful when it’s fixed up.

Why London?

Europe has changed quite a bit. London has become the financial capital of Europe, mostly because its tax laws are more favorable to collectors than those of France, for example. And because most of my artists were excited about the idea of showing in London.

It sounds like your decisions regarding the gallery are driven by your artists?

Definitely, they are.

I heard you spend a lot of time every day on the phone with your artists.

That’s true.

Your close relationship with your artists must be the joy of it for you.

It is the joy, but there are many serious collectors, museum curators, and directors with whom it is also a joy to work.

You were in the recent documentary Gerhard Richter Painting.

It was a shock to me. I had an appointment, walked into the studio, and Gerhard led me into another other room where the filmmaker was. She asked me to say something. I was taken by surprise, but I did.

The art world has changed enormously since you began. What do you think about the proliferation of art fairs?

I don’t feel good about it. I don’t think any gallerist does feel good about it, but there’s no avoiding participating in it, because it’s now an important part of the market. The paradigm has changed. It has changed the habits of the way the public engages with art. Although there are still many collectors who value galleries highly as places where they have a chance to see work in depth, fewer people come to the galleries. Many prefer to shop at fairs. They are often the same people who buy at auctions. That’s not always true, it’s not a black and white situation, but business has taken over the art world.

How many fairs do you participate in?

Many. It’s just a reality of an art world that has opened up to so many other countries. It’s a much bigger arena than it used to be. I don’t know how smaller galleries manage, I really don’t.

I don’t think fairs can replace galleries. Would an artist want to be with a dealer who didn’t have a gallery?

It’s a possibility; it depends on the artist. But the general practice is only galleries are welcome at the fairs.

But without a gallery how can you develop an artist, build a career? Maybe it will be a weeding out process.

I think you are right. I think it is very different to build a career without an exhibition space where the artist has a much greater possibility to be seen.

There are now biennials all over the world as well.

Of varying quality. Some are important—Documenta is the gold standard—and Venice of course is always of interest.

And now the auction houses are mounting shows.

That’s even worse; there’s no real commitment to the artist at all. Money is the driving motivation. If an artist is very much sought after, his or her treatment is better, and if not, artists beware.

Do you have many clients on the West Coast?

San Francisco is one of the great collecting cities of the world, and we have many important collectors in Los Angeles as well.

Are you tempted to open a gallery in another part of the United States?

No. We have a lot of out-of-town clients who come to New York regularly.

Do you work closely with museums?

Yes, very much so.

It’s very difficult for museums to acquire art now because most are priced out of the market.

We try to help museums financially to acquire works as much as we possibly can.

Are there any artists you regret not taking on?

I take a long time to decide to add an artist to the gallery because it is a very serious commitment, maybe even more so for the artist. The worst thing is to invite someone and then find it was a mistake. I don’t want to grab artists because they are hot. I have always added artists to the gallery before they were well known, or while they were in a more quiescent phase.

Joseph Beuys, “Mirror Piece,” from “Mirrors of the Mind,” 1975. Brown lacquered flask with iodine crystal mirror-plated interior, 7.25 x 4.25 inches. Published by Multiples, Inc. and Castelli Graphics, New York. Courtesy of Marian Goodman Gallery, New York / Paris.

Most of your artists have been with you for a long time; there haven’t been many defections.

Yes, that’s true.

Who is the most recent artist to join your gallery?

Adrián Villar Rojas. He represented Argentina in the Venice Biennale in 2011. I was really intrigued. He created this amazing environment, a world seeming to be made of stalagmites and stalactites, an otherworldly landscape. I thought it very original, thoughtful, powerful, and brave. I found it really stunning in the true sense of the word. I was deeply moved by it. All the things you look for in an artist.

Has he shown in your gallery yet?

No, he will sometime next season. He just finished a well-received exhibition at the Serpentine Gallery in London.

Where does he live?

In Rosario, Argentina, the hometown of Lucio Fontana.

Do you collect art yourself?

I don’t know if I would call it collecting, but I am attracted to many forms of art besides contemporary, which I am keen on. I like ancient sculpture from the Pre-Columbian era, sculpture from the Middle Eastern civilizations of the Tigris and the Euphrates, African art, American folk art, Japanese prints, and on and on.

For more information, visit Marian Goodman Gallery.

Previous articles from Print Issue 16 include: